Using Objects

Using Objects

- Primitive Types

- Example

- The Bad Way: Parallel Arrays

- Classes

- Instances

- Multiple Instances

- The Good Way: Object Arrays

- Thinking in Objects

- Cannot read property 'x' of undefined

- Object Functions

- Homework

Now you know how to create variables including arrays, and you know how to use for loops to repeat some code for each element in an array.

This tutorial introduces a new kind of variable: objects. Objects help you combine a group of related variables and functions into one unit, which helps you organize your code.

Primitive Types

So far, you’ve been using primitive types like numbers and booleans. A primitive type holds a single, standalone value. For example:

let x = 7;

When you read this line of code, you know that x holds a primitive value of 7, but you don’t know whether there’s an associated y value. It’s a single value, without any extra information.

Example

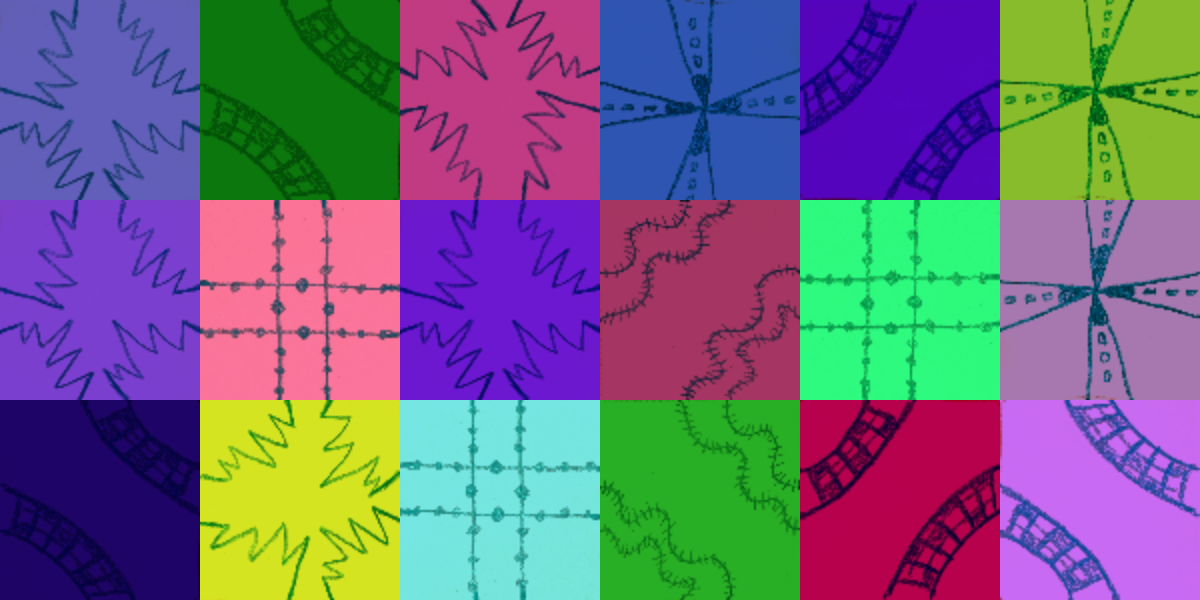

Let’s start with some code that uses two primitive values to show a falling circle:

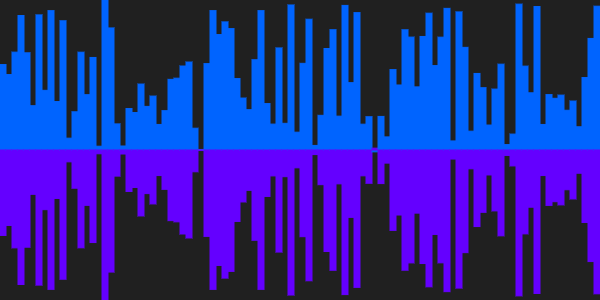

This code uses primitive x and y variables to represent the position of a falling circle.

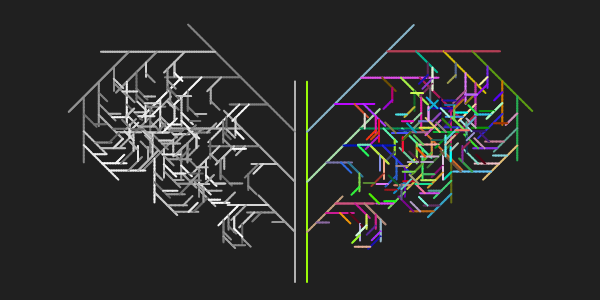

The Bad Way: Parallel Arrays

Next, let’s say you wanted to show multiple falling circles instead of just one. You might use one array to hold x values, and another array to hold y values:

This code uses two arrays: one that holds the x values of the circles, and another that holds the y values. This approach of using multiple arrays to hold related data is called parallel arrays. This approach works, but it’s generally considered a bad idea because it can be difficult to understand code that uses a bunch of different arrays.

Classes

You’ve seen primitive types like numbers and booleans, which hold a single value.

Primitive types hold a single value, and object types hold multiple related values. But how do you know what those related values are?

A class tells you about a particular object type. Similar to how you looked up primitive types in the reference, you can also find classes in the reference.

Specifically, take a look at the p5.Vector class.

Instances

A class is like a template that tells you what’s available inside an object. For example, the p5.Vector reference tells you that the p5.Vector class contains x, y, and z fields.

That means you can create a variable with an object type of p5.Vector, and that variable will contain x, y, and z fields.

To create an object, use the new keyword, followed by the name of the class, followed by parentheses () similar to a function call:

let myVector = new p5.Vector();

This code uses the new keyword along with the p5.Vector class name to create an object with x, y, and z fields. This is called an instance of the p5.Vector class.

Now that you have this variable, you can use the dot operator to set the fields of that instance:

myVector.x = 150;

myVector.y = 200;

Now the myVector variable holds a p5.Vector instance with an x value of 150 and a y value of 200.

(You could also set the z field, but the example only needs x and y so you can ignore z for now.)

You can also use the dot operator to access those fields, and you can pass them into a function just like any other value:

circle(myVector.x, myVector.y, 100);

Putting it all together, it looks like this:

This code creates a myVector variable and then uses the new keyword to create an instance of the p5.Vector class. It then sets the x and y fields of that instance, and then uses that instance to draw a circle.

Constructors

Take a closer look at this line:

myVector = new p5.Vector();

The new keyword tells the computer to create a new instance, and the p5.Vector() part tells the computer what class to create an instance of. The p5.Vector() part is also called a constructor because it constructs the instance.

The above constructor does not take any parameters, and the x, y, and z fields inside the instance it creates will point to default values of 0. This is also called a no-args constructor.

But like functions, constructors can also take arguments, passed in as comma-separated values inside the () parentheses. The “Syntax” section of the p5.Vector reference tells you what parameters the p5.Vector constructor can take.

For example, instead of setting the myVector.x and myVector.y values yourself, you can pass them into the p5.Vector constructor:

And here’s the original example using a p5.Vector instance:

This code uses a p5.Vector instance to represent a falling circle.

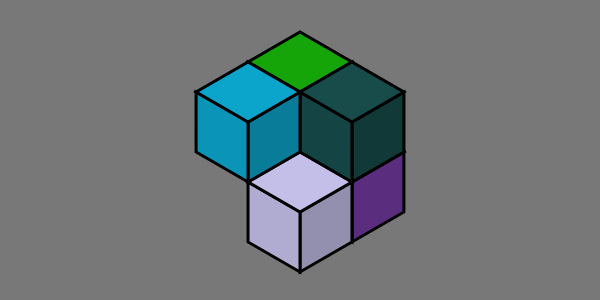

Multiple Instances

One of the most important concepts to understand with objects is that each instance is independent of other instances of the same class. Changing one instance doesn’t change the other instances.

For example, this code creates two p5.Vector instances:

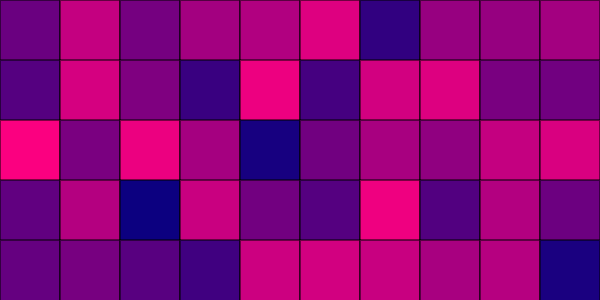

This code creates two variables, each pointing to a different p5.Vector instance. Notice that the red circle and the blue circle are independent. Updating the red circle does not update the blue circle, and vice-versa.

This is a powerful idea, and it lets you organize your code as it gets more complicated. It’s also pretty confusing, and “thinking in objects” can take some time. Try changing the above code to add a green circle using a third p5.Vector instance.

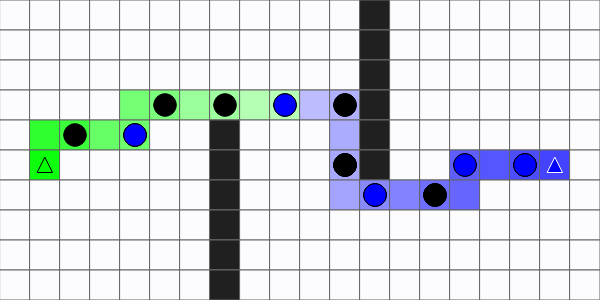

The Good Way: Object Arrays

Just like you can create an array of primitive values, you can also create an array of objects:

let circles = [];

This line of code creates a circles variable that points to an empty array.

for(let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

circles[i] = new p5.Vector(random(width), random(height));

}

This for loop fills the array with p5.Vector instances. Each instance contains a random x and y value.

Then you can loop over the array to move and draw each circle:

for(let i = 0; i < circles.length; i++) {

circles[i].y++;

if(circles[i].y > height) {

circles[i].y = 0;

}

circle(circles[i].x, circles[i].y, 25);

}

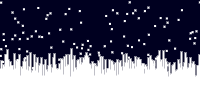

Putting it all together, it looks like this:

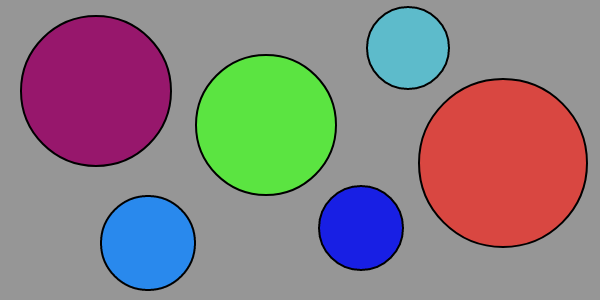

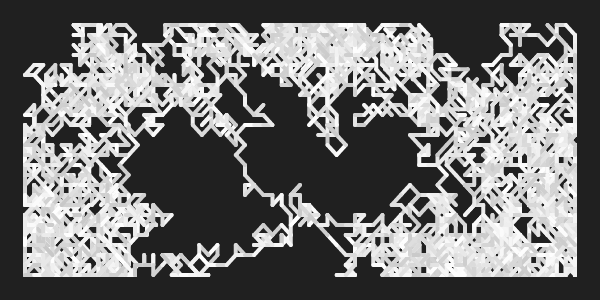

Thinking in Objects

Objects are a new way of organizing your code, but more importantly, they’re a new way of thinking about your code.

For example, when you think of a bunch of falling circles, you probably don’t think of them as a bunch of x values and a bunch of y values. You probably think of each circle as a cohesive unit, where each unit has an x and y value. Objects let you structure your code closer to how you structure the ideas in your brain.

This new way of thinking can be confusing. I remember being frustrated by it when I first started learning. But I also remember having an “ah-ha!” moment after working with objects for a while, where I finally understood them. I honestly believe that it has affected the way I’ve thought about not just code, but also the real world ever since.

So if all of this still feels confusing, that’s okay! It’ll become more natural as you write more code and see more examples that use objects.

This way of “thinking in objects” is called object oriented programming and it’s at the core of many languages and libraries.

Cannot read property 'x' of undefined

Encountering errors and needing to debug problems is a normal part of writing code. And now that you’re using objects, you’re very likely to encounter a new type of error: the dreaded Cannot read property 'x' of undefined.

For example, what do you expect happens when you run this code?

let myCircle;

function setup(){

createCanvas(300, 300);

}

function draw(){

circle(myCircle.x, myCircle.y, 100);

}

If you try to run this program, you’ll get this error:

Uncaught TypeError: Cannot read property 'x' of undefined (sketch: line 8)

Undefined

To understand this error, think about the default value of variables. What is the value of x after this line runs?

let x;

This line creates a variable named x, but doesn’t assign it a value. In other words, the value of x is undefined.

You can test this out with code like this:

In other words, if you don’t specify a value, then you can pretend that you’ve specified undefined as the value:

let x = undefined;

The Cannot read property 'x' of undefined error is caused by trying to use the dot operator on an object variable that points to undefined.

That’s why this code generates the error:

let myCircle;

function setup(){

createCanvas(300, 300);

}

function draw(){

circle(myCircle.x, myCircle.y, 100);

}

This code tries to get the x and y values of myCircle which is set to the default value of undefined. And since undefined means that no object has been created, the computer doesn’t have an object to “ask” for its x and y values, so it generates the error instead.

To fix this type of error, you need to make sure any object variables you’re using are pointing to an instance:

Also note that the same thing is true of object arrays! For example:

let circles = [];

This line of code creates an empty array. If you tried to use one of the elements in the array:

circle(circles[0].x, circles[0].y, 100);

You would get an error, because the element at circles[0] is undefined. That’s why you need to fill the array with instances first:

for(let i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

circles[i] = new p5.Vector(random(width), random(height));

}

When you encounter a Cannot read property 'x' of undefined error, try using console.log() statements to figure out which variable is undefined, and then make sure that variable points to an instance instead of undefined.

Object Functions

Now you’ve seen that classes contain fields. For example, the p5.Vector class contains x, y, and z fields. Each instance of the p5.Vector class is an object that contains its own x, y, and z fields, and each instance is independent of other instances.

In addition to containing fields, classes can also contain functions. Functions inside a class usually modify the state of an instance by changing the values of its fields, or they take some action based on the values of the fields.

As always, the p5.js reference is your best friend. The p5.Vector reference lists all of the functions you can call for instances of the p5.Vector class. For example, the p5.Vector class provides an add() function that adds values to the x, y, and z fields of a specific instance.

To call an instance’s function, use the dot operator, then the name of the function, then any parameters the function requires in parentheses ().

Specifically, notice this line of code:

myCircle.add(0, 1);

This line of code calls the add() function on the myCircle variable, which points to an instance of the p5.Vector class. The 0 and 1 represent how much to add to the instance’s x and y fields respectively. After this line of code, the y field inside the myCircle instance will increase by 1.

This might not seem very useful yet, but it comes in handy when you start using more complicated objects.

Homework

- What is the difference between a class and an instance?

- Think about some real life objects. What fields would be in their class? What values would instances of that class have?

- Modify the above program to use the

zfield of thep5.Vectorclass to hold a different size or speed for each falling circle.