When Failing isn't Failure

When Failing isn't Failure

Ludum Dare is a game jam where participants have 48 hours to make a game around a theme that’s announced at the beginning of the event. In my previous blog post, I mentioned that I planned to use Ludum Dare 42 as an opportunity to prototype the Android game that I want to make this year.

I wanted to make a game that explored the idea of running an ant colony. Instead of controlling any one ant, you’d pick certain types of ants to hatch (soldier ants, builder ants, foraging ants, digging ants, etc) and the game would otherwise play itself.

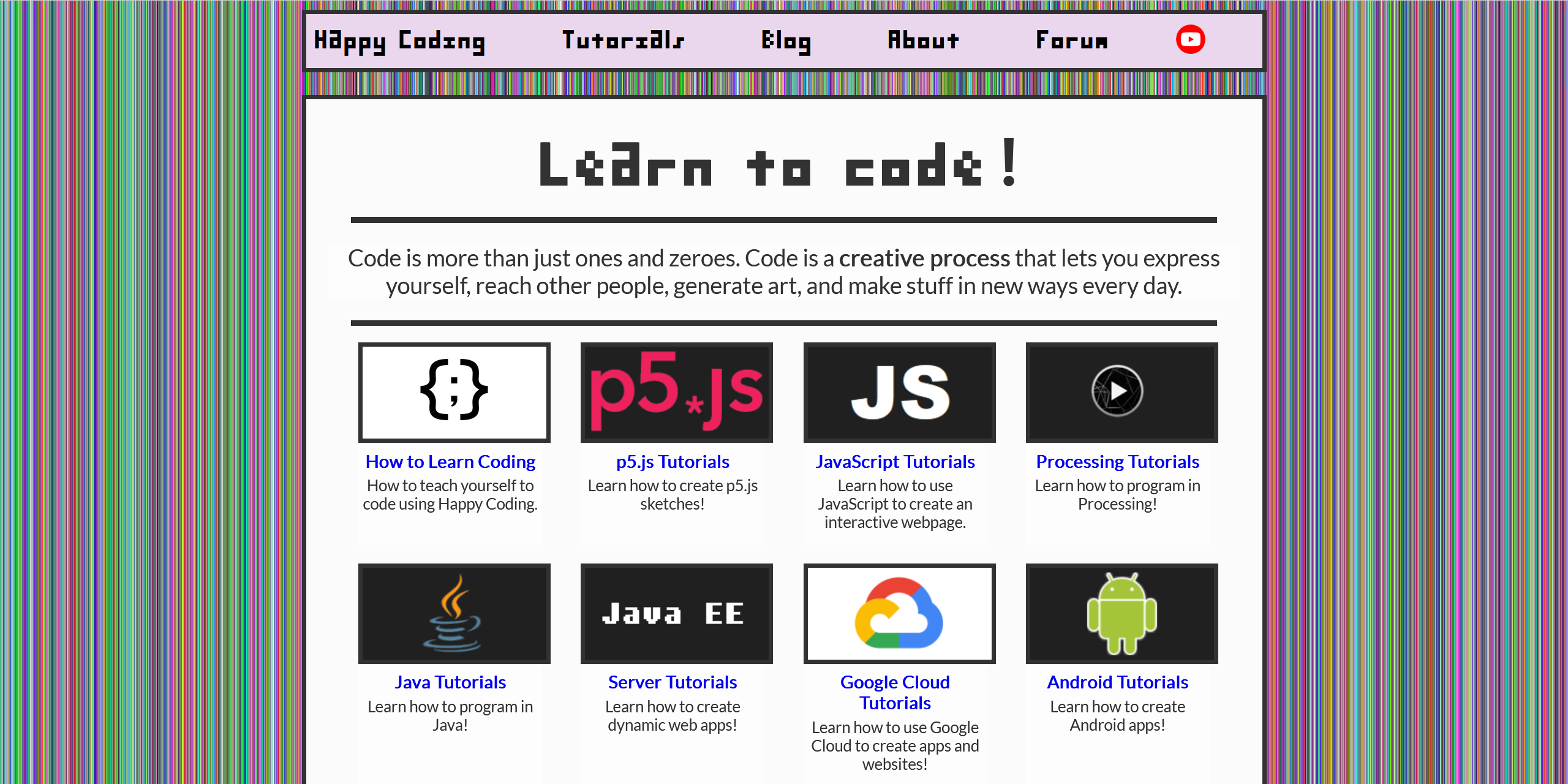

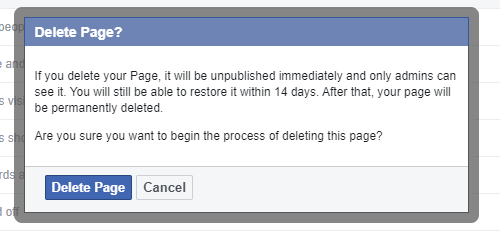

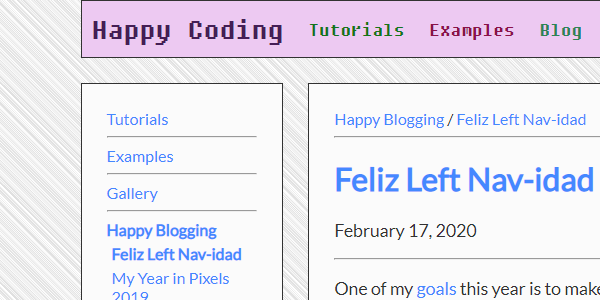

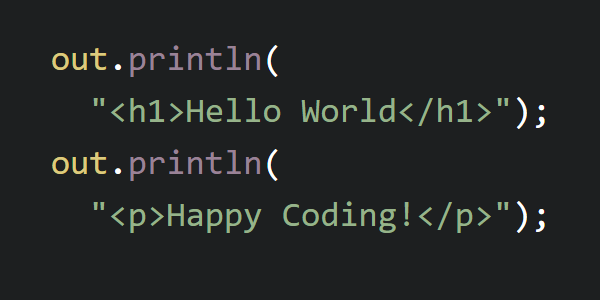

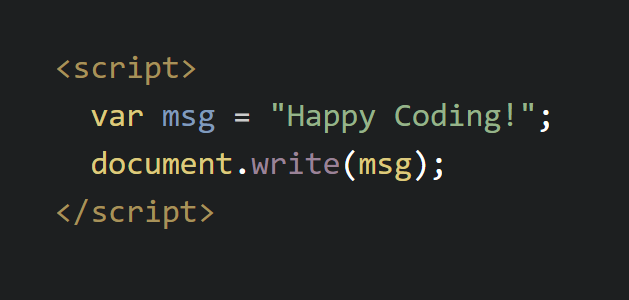

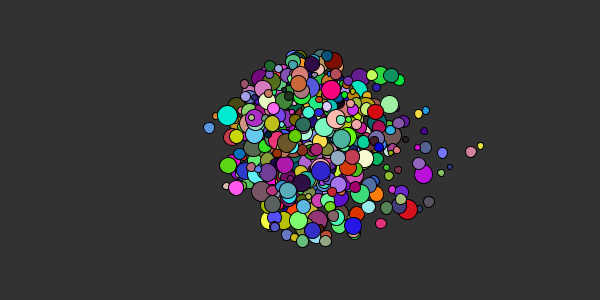

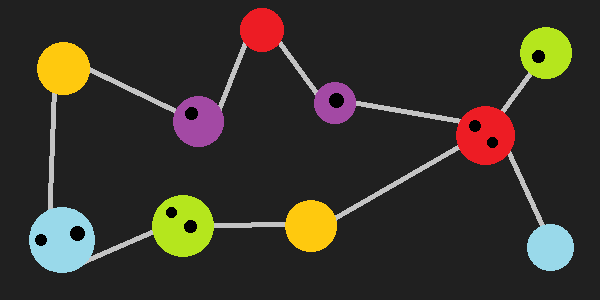

The game would be a simulation that required managing resources: maybe you need to forage food to build a soldier ant, who defends against enemy ants, who will try to steal your water, which you need to build foraging ants. It would look something like this:

The idea is that each colored circle is a different type of “room” that requires and generates certain resources, and the black circles are ants that move resources around as needed.

My plan was to make a simple version of this over the weekend for Ludum Dare.

Day One

Ludum Dare started on Friday afternoon, and the theme was announced: running out of space.

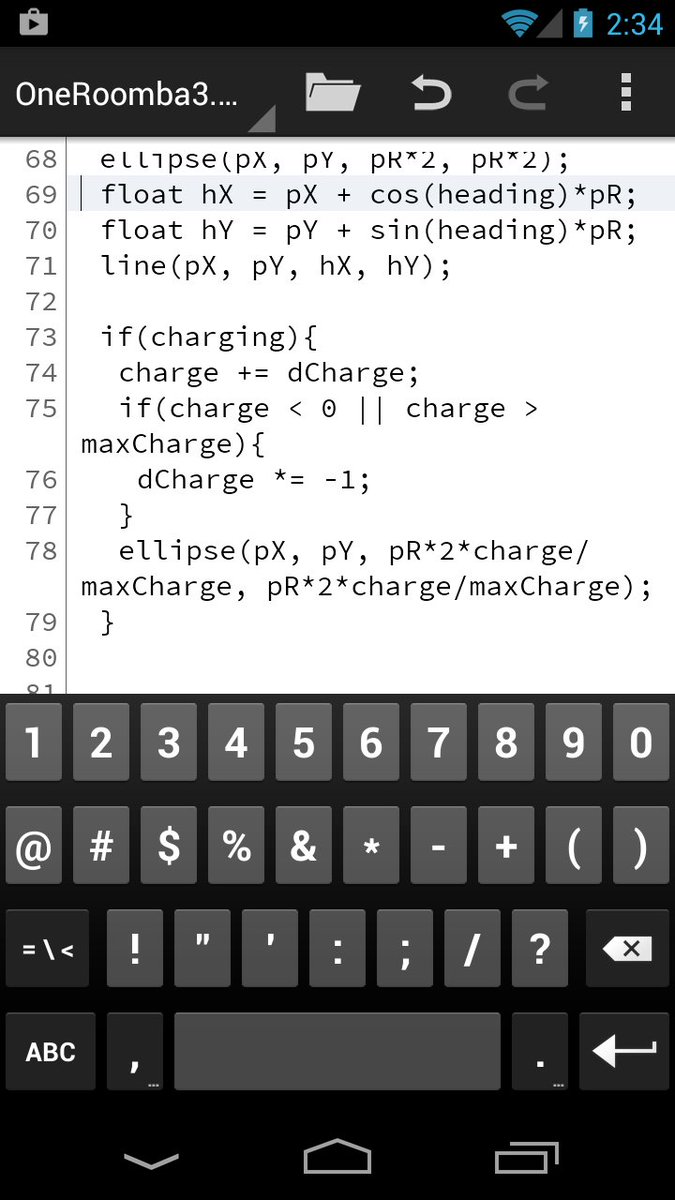

I got home from work and started coding. I knew I needed an environment where nodes were connected via paths, and ants could navigate between them. I created the basic data structures, Node, Agent, Resource, etc. Wrote some rendering code that draws them, and some test code for generating environments. So far so good, now it’s time for some path finding!

I half-wrote a few implementations to try some ideas out: I considered a brute force approach, and then I figured I could get fancy and use Dijkstra’s algorithm. But wait- maybe libGDX comes with a pathfinding library I can use instead of reinventing the wheel?

Turns out it does! The gdxAI library comes with a pathfinding API that looked pretty promising. One issue I encountered early was a lot of tutorials are out of date and use classes and functions that aren’t available anymore. And the tutorials that were up to date involved a lot of background algorithm info that I didn’t really care about. I just wanted to get something simple working!

I spent most of Friday night playing with this but not getting very far. I was trying to add the pathfinding library on top of my existing data structures, and it wasn’t working very well. Hmph.

Day Two

I woke up Saturday morning thinking that I’d probably start from scratch. I sat down to try to debug one last time. I got a simple example working separately from my game, and then I noticed a dumb mistake: I had assumed that updating my game world data structures would automatically update the pathfinding data structures, but it turns out this wasn’t true! You have to recalculate the pathfinding data structures every time you modify your game world data structures. With this change, my “game” (which at that point was one dot travelling between three circles) was working perfectly.

Ludum Dare gives you a theme that your game is supposed to be about, and at that point I just had a vague idea about ants and self-playing simulations. How could I fit the “running out of space” theme into my idea? My great epiphany was this: instead of ants, I’d have rocketships; instead of rooms, I’d have planets; and instead of resources like food and water, I’d have resources like moon cheese and meteor rocks.

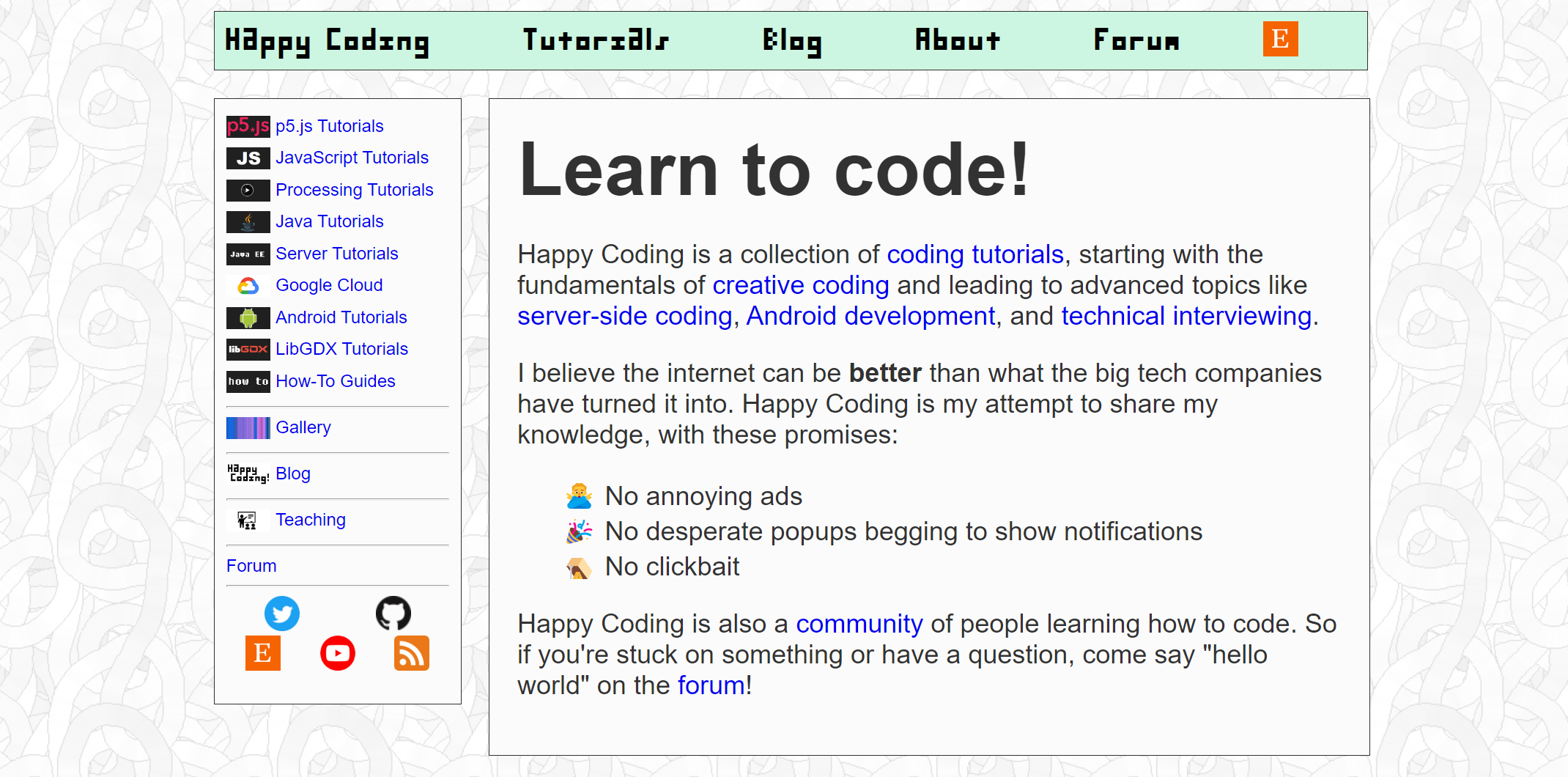

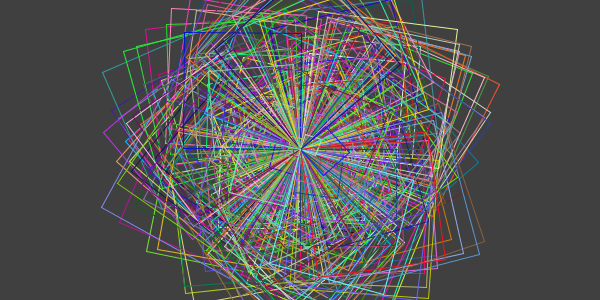

At this point, I had a basic working version of my simulation!

This doesn’t look like much, but the cool thing here is that the ant (sorry, rocketship) is figuring out that the node (planet) needs a certain resource, figuring out where that resource is, and then plotting out a path to the resource and then to the planet. This also works with bigger simulations with a bunch of planets!

I spent most of Saturday adding different types of planets, ships, and resources. This is where things started to go a bit off the rails. I still didn’t have a real game yet: I didn’t have any goals or win conditions in mind, and my code was getting pretty buggy. I was dealing with rocketships that would go straight from one planet to another without going through the path, and other rocketships that mysteriously got faster every time they touched a planet. I debated starting from scratch several times, but in the end I kept building on top of what I already had.

This is the double-edged sword of game jams and hackathons: the time constraint can be a motivator, but it also means that you can write some pretty bad code. In my case, this ended up slowing me down as I had to debug code that was spread out and hard to follow, and making changes to the code was slower than if I had spent the time to design it better.

I ended up staying up pretty late coding Saturday night, which didn’t help my brain at all.

Day Three

I woke up with a fuzz brain, but I eventually figured out how to turn my simulation into a game.

You’re the leader of a space empire, and your universe is dying. You start out with a single planet with a few resources, and you have to expand until you have enough resources to travel to a new universe. You have a few types of ships:

- Builders take resources from existing planets to build a new planet.

- Carriers transport resources from one planet to another.

- Workers extract new resources from planets.

And you have a few types of planets:

- Your home planet can build new ships.

- Asteroids produce space rocks.

- Moons turn space rocks into cheese.

- Suns combine space rocks and cheese to make fuel.

To win the game, you have to add ships and planets in the right order to accomplish specific goals: build 10 rocks, make 5 moons, etc. Most of my day Sunday was spent coming up with a few levels that introduce these concepts over time.

At this point, it started getting pretty Cones of Dunshire-y. The underlying simulation was simple enough, but explaining it was pretty complicated. I didn’t have enough time to build out levels that introduced things in an understandable way.

So as the deadline came and went, I admitted that I wasn’t going to be able to finish a game, let alone one that was understandable enough to play. Ludum Dare 42 was a failure for me.

When Failure isn’t Failing

Despite not submitting a game, I’m pretty happy with the progress I made over the weekend. I figured out how the libGDX pathfinding API works, and I figured out a few design decisions: specifically, I need to start with the pathfinding API and build my simulation on top of that, not the other way around.

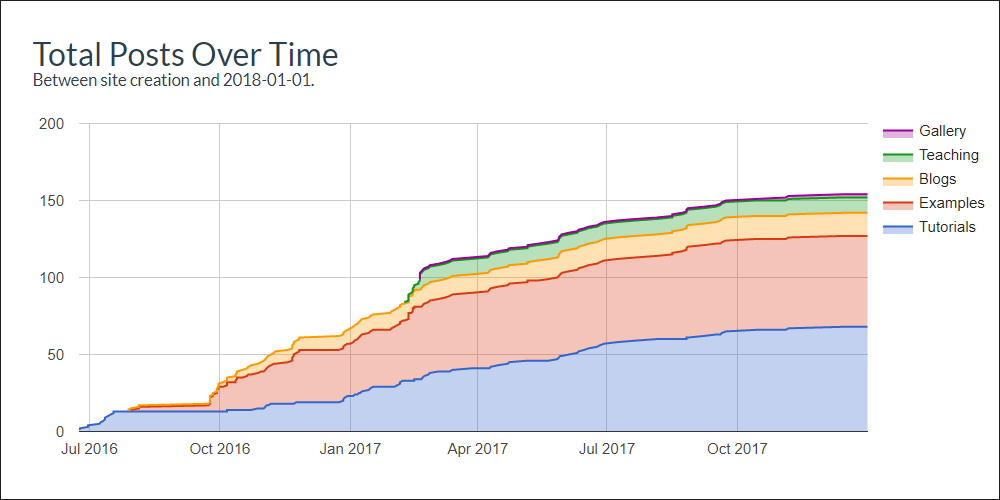

I’m planning on putting together a tutorial on the pathfinding API, which will hopefully help other people like me who are frustrated by all of the out-of-date information out there on the internet. I’m also going to start my game over from scratch, build it the way it should have been built from the beginning, and spend some time thinking about level design so I can better introduce the concepts needed to play the game.

I believe that the key to doing awesome stuff is having a set of short-term, achievable goals that work towards a longer-term vision. The short-term goals should be pretty bite-sized, and a weekend of Ludum Dare-ing is a perfect example. Often you’ll realize that one of your goals is actually a few separate goals, and that’s okay! Take a step back, add those smaller goals to your todo list, and take another crack at them.

That’s what happened here. It turns out that my goal of making this game was actually a few smaller goals: figure out pathfinding, figure out what the “game” part of it was, figure out level design, build a tutorial into the story, and spend some time on art and polish.

Even though I wasn’t able to do it all, I did manage to cross a few of those things off the list this weekend- and that’s pretty great progress. (Especially compared to the alternative of playing video games or watching netflix all weekend!)

The Problem Solving Map

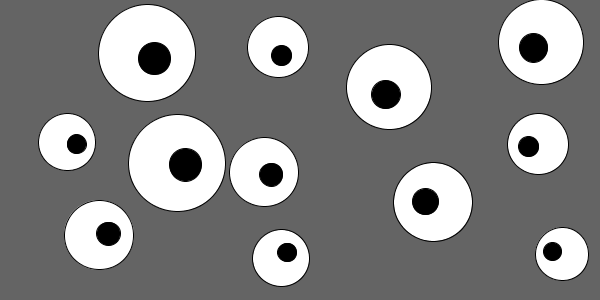

Some of the above might be a little surprising, because most people think that problem solving looks like this:

If you have a problem, you just use your intelligence and creativity and figure out a solution. Easy!

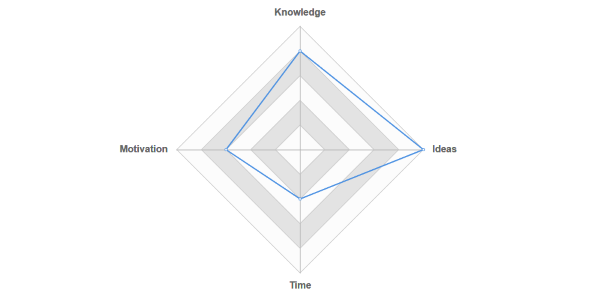

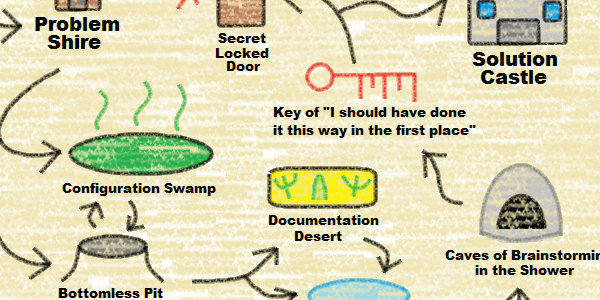

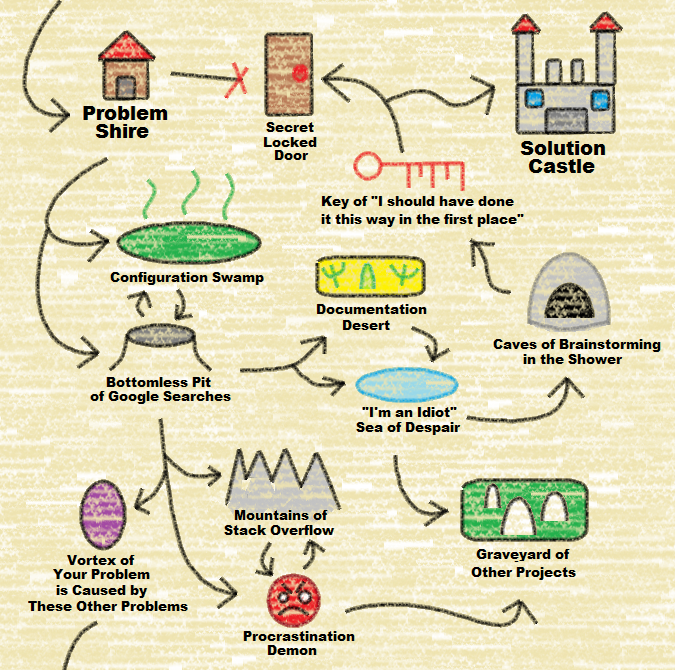

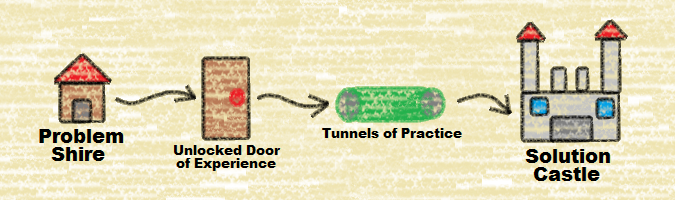

But in reality, problem solving looks like this:

Problem solving involves a lot of false starts, dead ends, banging your head against the wall, and generally not feeling very smart or creative.

This is why I hate sentences like “I could never do that, I’m not creative enough” or “this stuff is so easy for you” - because the truth is that nothing is easy, and creativity doesn’t come naturally to most people. The trick is to put the work in, and work in small steps toward a larger goal.

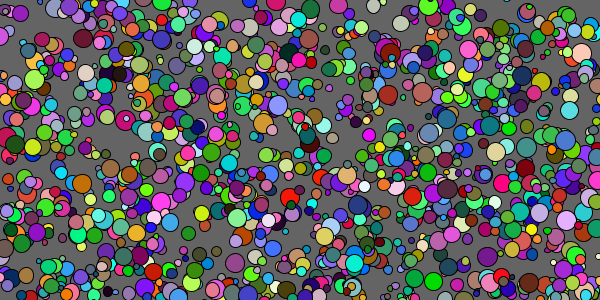

If you keep that up, eventually you can find the shortcuts so your problem solving map looks more like this:

But to figure out what you should do, you also need to figure out what you shouldn’t do. That’s actually a really important part of the process, and it’s why failing isn’t failure- as long as you learn from it and get back to doing the work.