Checking My Privilege

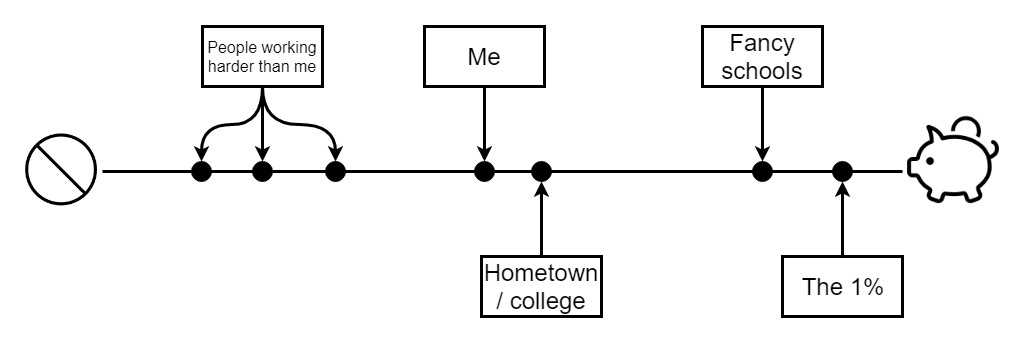

Checking My Privilege

- A Brief History of Kevin

- The Myth of Meritocracy

- Impostor Syndrome

LuckPrivilege- Self Image

- The Myth of Comparison

- Otherism

- Different Perspectives

- The Limits of Caring

- Recognizing Power

- Surround yourself with people who will call you out

For most of my life, I’ve defined myself in terms of the struggle: a lot of my self-worth came from the idea that I worked hard to get where I was. This made it difficult to listen when people talked about privilege, especially when other people talked about how they perceived my privilege. I don’t feel like my life was particularly easy, and in fact I’m proud of how far I’ve come despite (or because of) my background. Me, privileged? No way.

But over the past few years, I’ve been thinking more about my privilege and my interactions with the world. Maybe it’s a result of meeting people from many different backgrounds, or a result of the various discussions about privilege on Twitter, or a result of my own changing perspective. This post is an attempt to collect some of those thoughts, with the hope that it might help other people think about their own privilege.

A Brief History of Kevin

I think people tend to mythologize themselves a bit too much, but part of my goal with this article is to try to reflect a bit, so with the giant disclaimer that this feels a little gross to me, here’s my origin story.

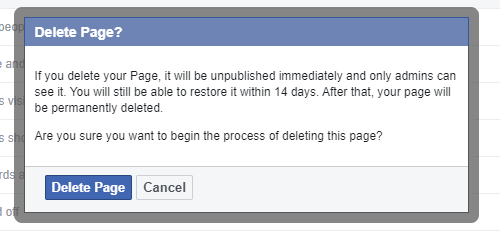

I was born in a small town. Here’s a picture I took from the backyard of the house I grew up in:

Moo!

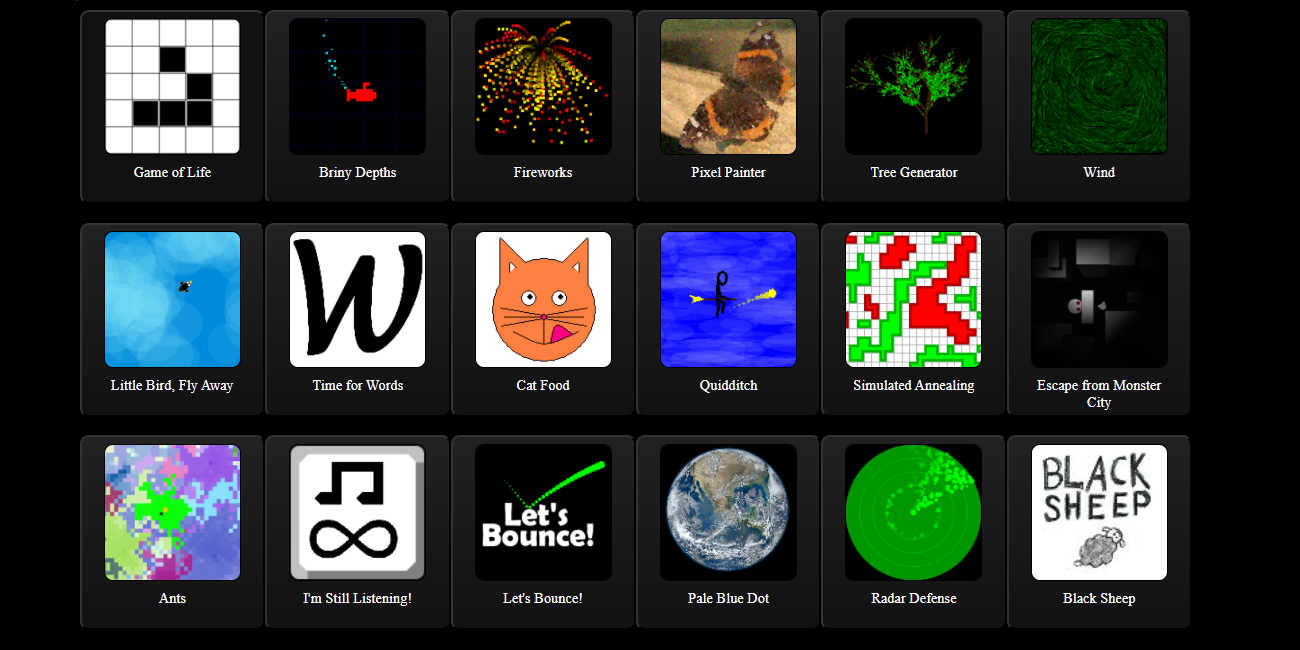

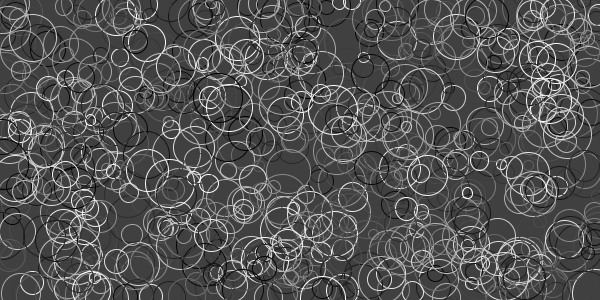

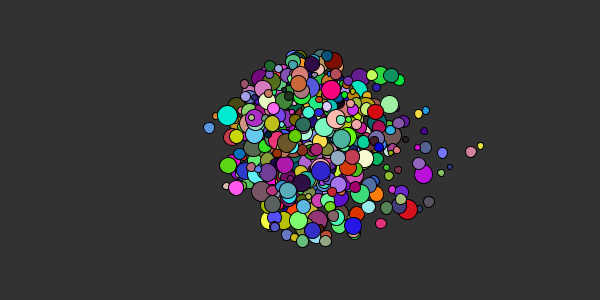

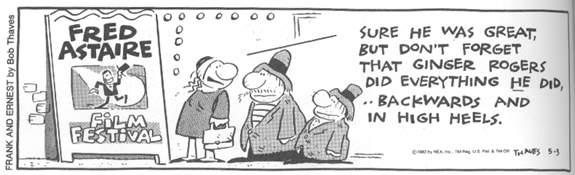

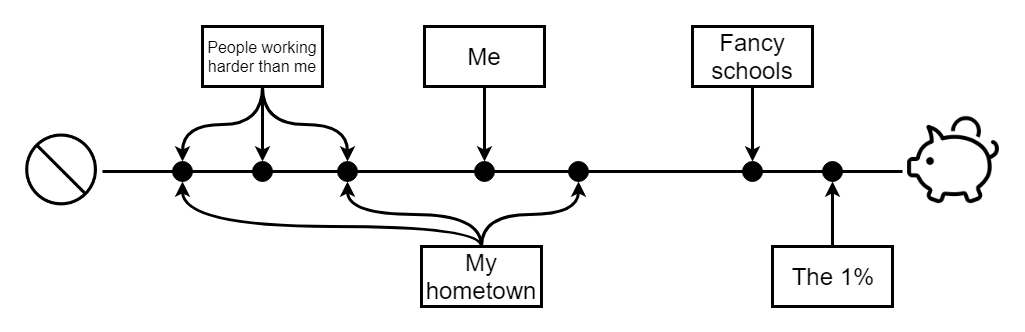

I grew up very blue-collar, hunting and fishing, and shopping at K-Mart, Payless, and yard sales. And I was very aware that this meant I was -gasp- poor, mostly because other kids told me so. Let’s say I’m about 10 years old at this point, and most of my world is the elementary school I attended. If you had asked me to graph out my understanding of the world, it would have looked something like this:

I knew that getting your shoes at Payless was something that other kids made fun of. I knew my best friend got every new video game, and I could only rent them. I’m not saying these are particularly profound observations, but some of my earliest memories involve the knowledge of my “place” in the world.

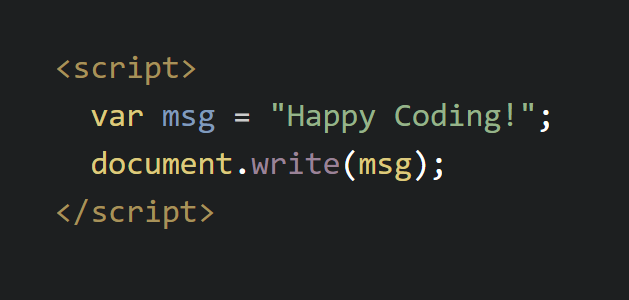

Fast-forward a few years. I had a job all throughout high school, and I took “career track” classes about installing drywall and repairing lawnmowers rather than “college track” AP classes, because I wasn’t planning on going to college. I did take a computer science class, mostly because I liked the teacher who taught it.

In high school I had a sorta-kinda “plan” to go into the military, which is one of the only options for most people who come from where I come from. I would drive to the recruiting center and sit in the parking lot preparing to go in and sign the papers, but I never quite got to the door. A few months before graduating high school, I decided at the last second to be an English teacher. So off to college I went. I changed my major to Computer Science pretty quickly, but that’s a different story.

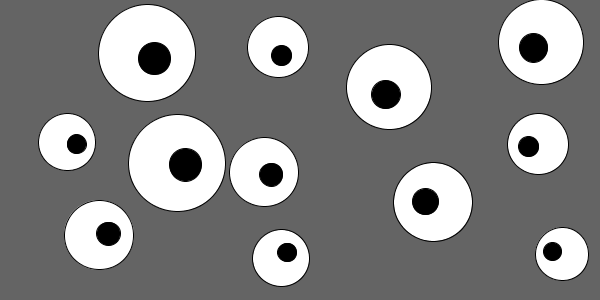

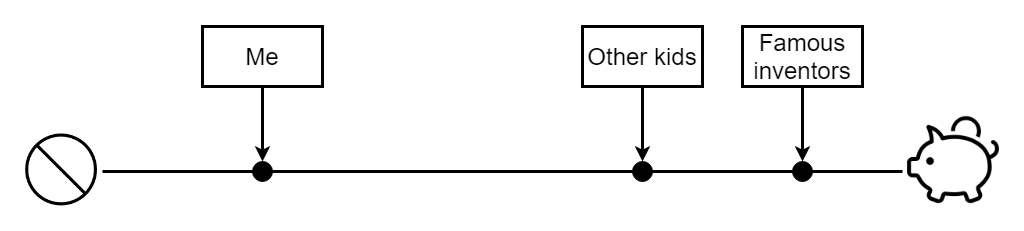

I attended college by working a few different jobs and making a bunch of terrible decisions about student loans. I was very aware of people whose parents were paying their tuition. I went to a state school, and I absolutely hated the neighboring private college. One semester at that private school cost more than 4 years at my college. These rich fratboys made the wealthiest kids from my elementary school look like, well, kids who shopped at Payless. I was around 19 at that point, and if you had asked me to graph out my understanding of the world again, it would have looked something like this:

On the other hand, I was proud of the struggle. Sure, waking up at 6, working for a few hours at my morning job, going to school, and then taking the bus to my night job just to do it all again the next day was stressful. But it meant something. It meant I was strong in ways people who didn’t share that struggle were not. This struggle was a really important part of my identity.

The Myth of Meritocracy

At this point in my life I would have agreed with the idea of meritocracy: people who work the hardest should reap the benefit. I would have been vaguely against affirmative action: after all, I had to work hard to get where I was, so why should anyone get a “shortcut”?

And then the summer before I graduated college, thanks to my undergrad advisor telling a clueless me to apply, I participated in NIST’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship. This is basically an internship where 100 college students live in a hotel and work at NIST for a summer.

For one reason or another, the people I grew closest to that summer were a group of students from Puerto Rico. I found I had more in common with them than I did with most of the other students: many of us in that group were first-generation college students, paying our own way, and feeling more than a little out of our element surrounded by people wearing lab coats in government research buildings.

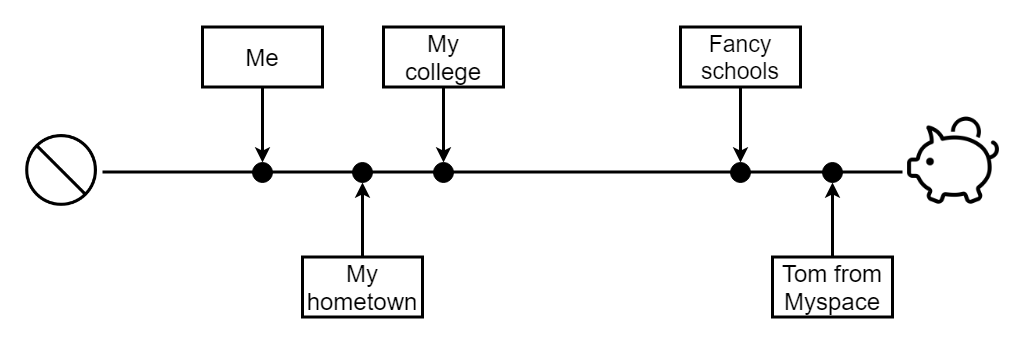

And I realized something: they were doing everything I was doing, everything I had felt made me stronger or even better than people who had it “easier” than me. And they were doing it in their second language, 1500 miles from home. They had to work harder than I did. I had it easier than them.

I also noticed that things felt a little cliquey. The white kids weren’t doing anything wrong really, but it was impossible not to notice who got invited to various parties or adventures. I could “blend in” with the other white interns a little more easily, but it just felt a little off.

This was when I stopped believing in the idea of meritocracy. It’s not enough for some people to “just” work hard. They’re already working impossibly hard. Making sure the process includes them is absolutely not a shortcut. They absolutely deserve it.

My graph of the world zoomed out a little bit more:

Impostor Syndrome

Then I graduated college, put my resume up on Monster.com, and took the first job I was offered. I ended up working as a subcontractor for the Federal Aviation Administration. I was surrounded by extremely smart people; many of my coworkers were doctors from MIT literally doing rocket science. In contrast, when explaining where I worked I often accidentally said I worked for the FFA (Future Farmers of America, which I was a part of back in high school) instead of for the FAA.

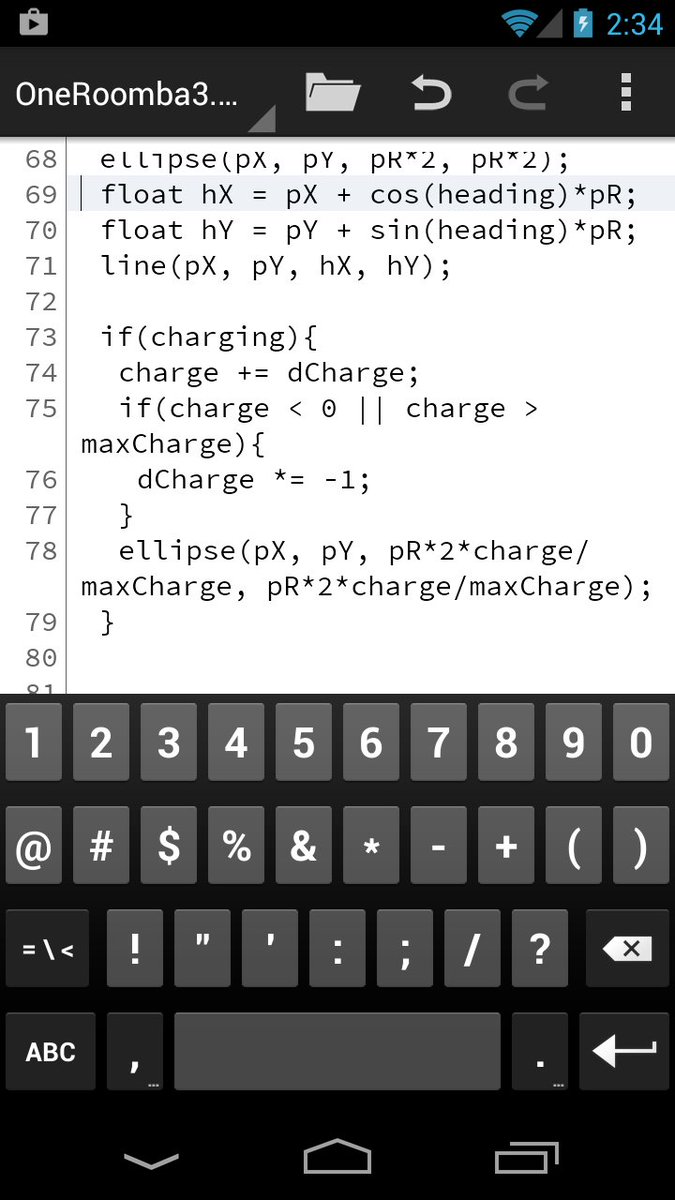

The impostor syndrome was real. I carved out a little niche for myself as “the Java guy” by relying on skills that I mostly learned back in my high school Java class and from random Java forums, but I still felt like a kid from the cornfields of Lancaster county. I knew I wasn’t doing the “real” research work that my coworkers were doing. I also knew that I wasn’t a “real” programmer like they had out in silicon valley. I was relatively happy, but I certainly didn’t feel very privileged, or like I was in a position of power.

Luck Privilege

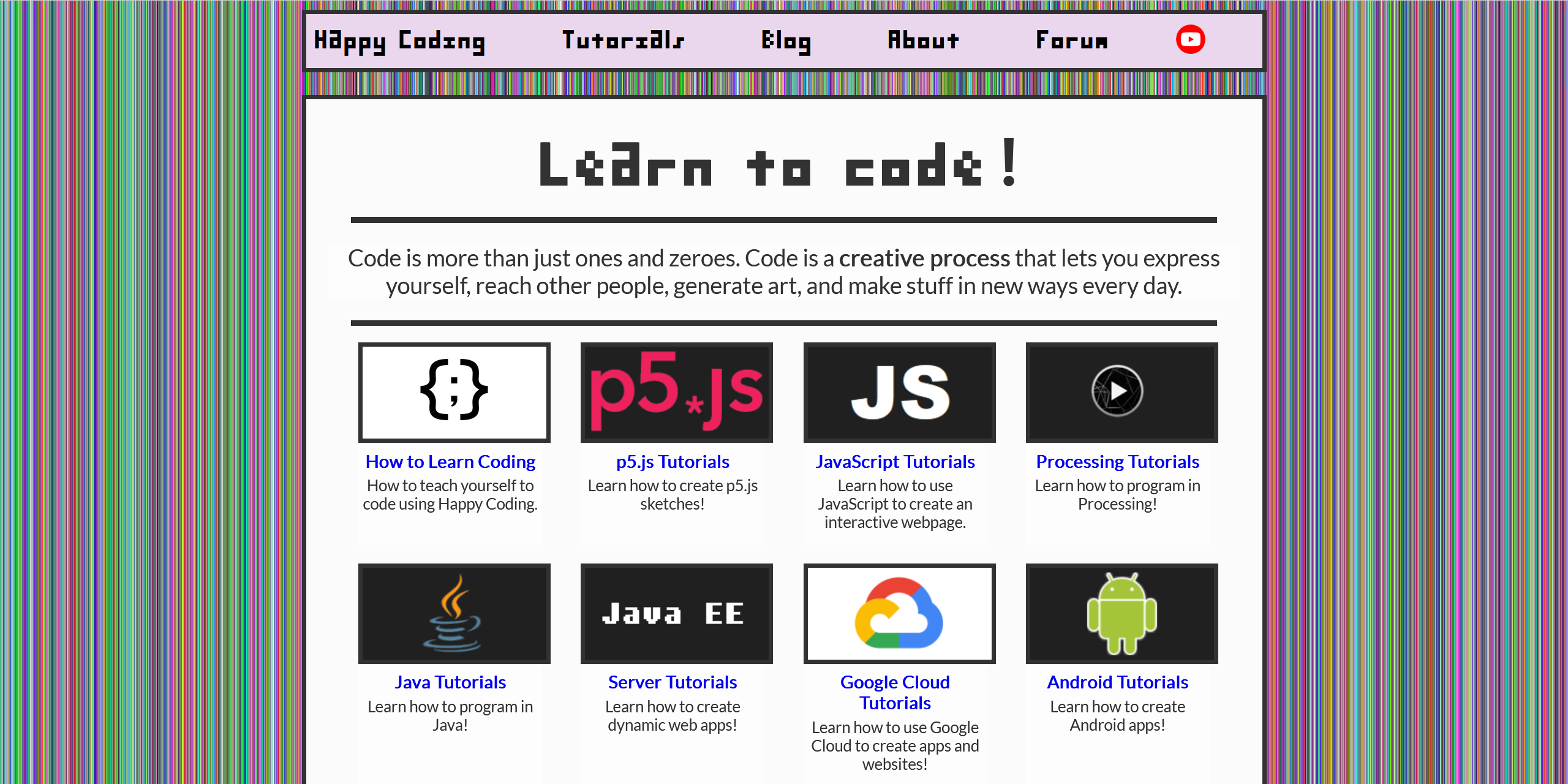

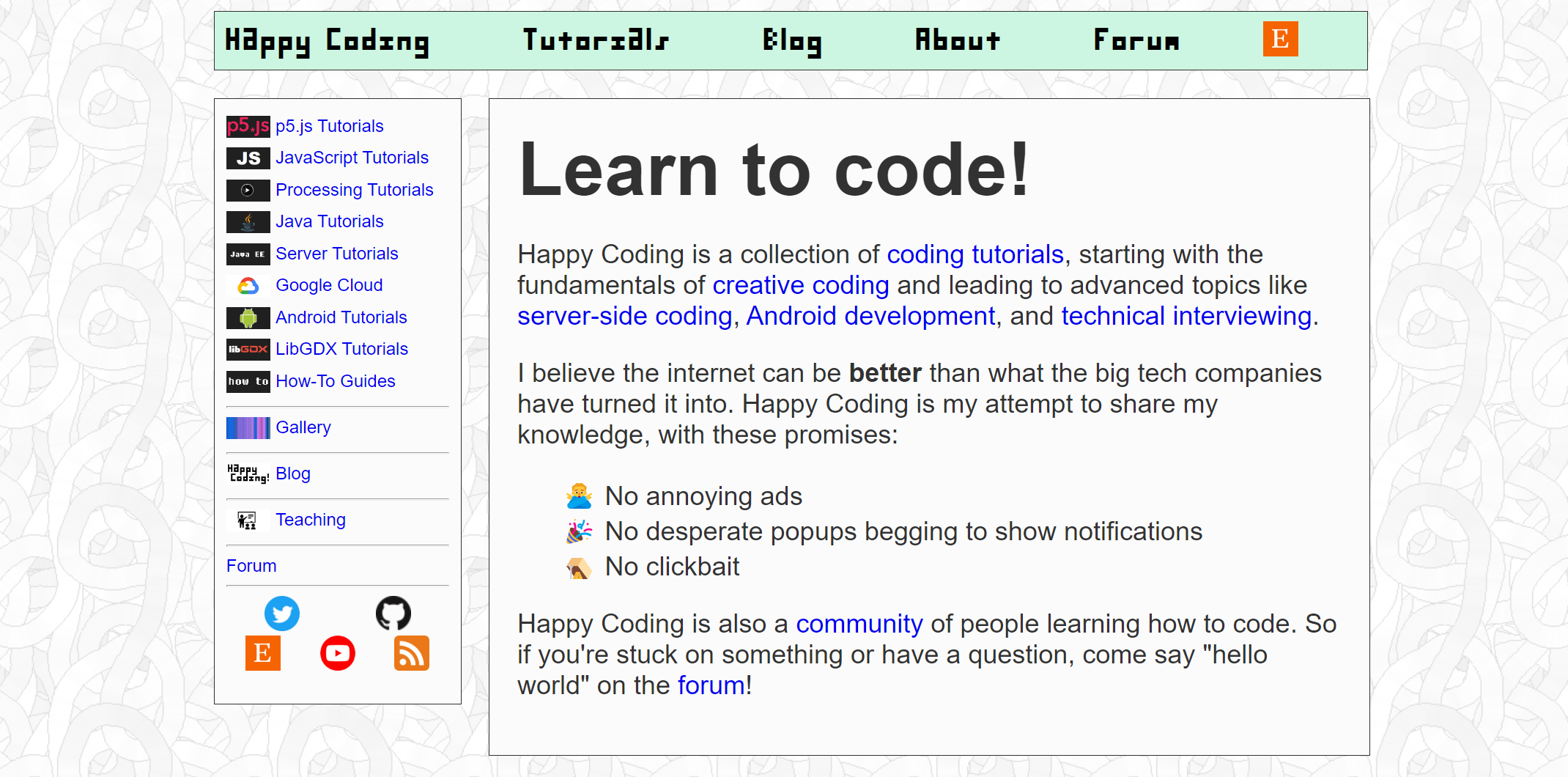

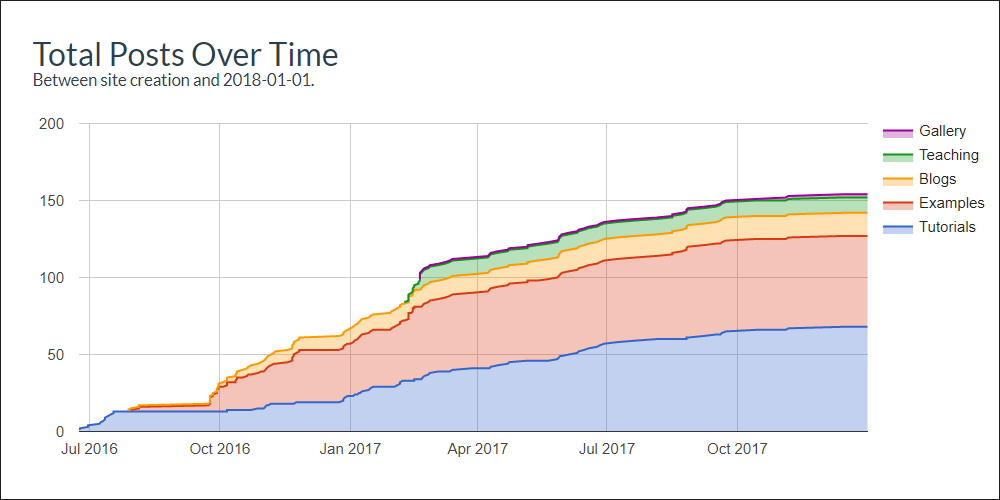

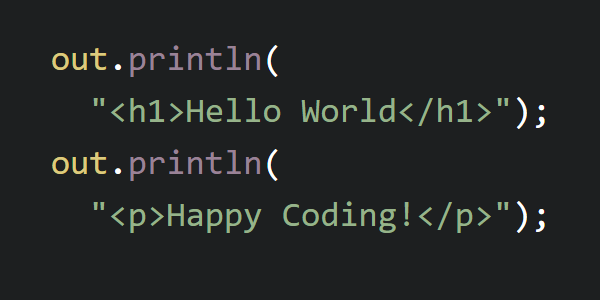

Then a funny thing happened. Over the years, I’d been getting more involved in online mentorship through Static Void Games, Stack Overflow, and various forums. When I first started thinking about Happy Coding, I reflected on why I enjoyed this mentorship.

Part of the answer to that is: I was lucky enough to have a math teacher in high school who recognized how important computer science was, so he taught himself how to code, put together a brand new programming course, and begged his students to take it. I was lucky enough to attend a high school that had a computer lab. I was lucky enough to have a computer at home throughout high school, and I was lucky enough to have the spare time to play with it. I wanted to pay that “luck” forward.

But I realized something: this “luck” was the privilege that people had been talking about. I wasn’t lucky, I was privileged. I was privileged enough to have a math teacher in high school who recognized how important computer science was. I was privileged enough to attend a high school that had a computer lab. I was privileged enough to have a computer at home throughout high school, and I was privileged enough to have the spare time to play with it.

Many people didn’t have these privileges. Even today, when people think of computers as being ubiquitous, many students don’t have access to computers, either at school or at home.

(You can see this realization in the very first Happy Coding blog post I made.)

This subtle distinction allowed me to look at my life from a new perspective. Growing up, I thought I was poor, because the other kids made fun of my Payless shoes. But in reality, I was lucky / privileged enough to have a roof over my head, to never go hungry, and to have access to resources that not everybody has access to. I thought I was strong because I worked hard. But in reality, many other people were working much harder than I was: I wasn’t dealing with any health problems, or taking care of any dependents, or coping with any trauma, for example.

I know how obvious all of this sounds in hindsight, but it honestly took me until I was in my thirties to understand that the kids that made fun of me for getting my shoes at Payless also got their shoes at Payless. And although I thought of myself as not having much money, the reality is that many kids I grew up with had less than I did. I just couldn’t see them because I was too busy feeling self-conscious about myself.

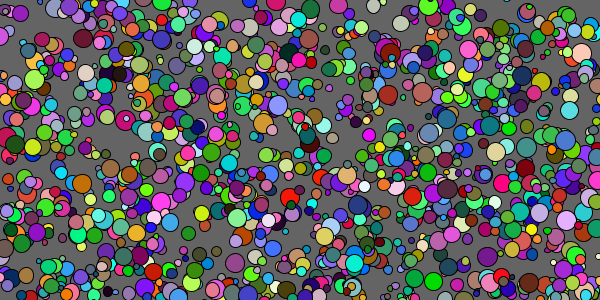

My graph of the world zoomed out a little bit more:

There are many ways to look at this, but one of the core questions I often ask myself is: In what ways are you lucky? Then I take that list, and I try to reflect on what that means about my privilege.

Self Image

This realization was difficult for me, because I had put a lot of value in the self-image I created about myself. My self-worth came from thinking of myself as hard-working, so by admitting that other people worked harder than I did, in a way I was losing some of my self-worth.

I think people, including me, tend to mythologize ourselves, to cling to ideas about what makes us special. We all have an imaginary version of ourselves in our brain, the version of ourselves who lives up to all of our expectations. Part of this is a good thing, as it gives us something to aspire to: I work hard, I help others in need, I fit into these groups, etc. But on the other hand, it’s hard to face any facts that are outside of that self-image.

One obvious example: no reasonable person thinks of themselves as racist. This makes it really hard to talk about stuff like implicit bias. Of course I don’t assume anything about people of a certain race, I’m not a racist! It’s hard for even well-intentioned people to reflect on this, because it contradicts the self-image they have about themselves. It doesn’t feel good to think about the various ways I might be making somebody else’s life harder. But if I don’t try to become aware of this, then I’ll never improve. (For more on this, I recommend checking out this Youtube video.)

The self-image version of yourself can also be an excuse to not put in the real work required to achieve your goals. Who is going to be a better artist: the person who buys a lot of expensive tools because they want to see themselves as an artist, or the person who authentically practices every day?

I’ve said before that I don’t like to talk about projects before I finish them, because talking about them makes it less likely I’ll actually finish them. This is the closest thing to a superstition that I have, but I honestly believe it. And I think the mechanism behind it is that talking about a project gets you closer to that self-image version of yourself without putting any of the real work in. Why do the thing when you can just talk about the thing instead?

So with that in mind, I try to be very critical of the self-image version of myself I have in my brain. I try very hard not to mythologize myself, and to recognize the aspects about myself I tend to advertise to other people, because that’s where I’m least likely to seek improvement or put the genuine work in. One specific question I ask myself quite often is: do I enjoy helping people, or do I enjoy the self-image of helping people? I don’t have a great answer to that question, but I think it’s an important question to ask. It helps me touch base with reality, and make sure I’m actually doing what I set out to do.

I don’t want this to turn into me giving advice to other people, but I’d encourage everyone to think hard about what their self-image looks like. What traits do you most admire in yourself? What aspects of yourself do you most want other people to see? And then look at that with a critical eye: how much of that is actually true? What can you do to be more authentic? What credit can you give to other people?

The Myth of Comparison

Another thing that makes it hard for me to let go of the mythical self-image I have of myself is that it’s also really easy to compare yourself to other people. More specifically, it’s easy to focus on what other people have that you don’t have. It’s much more difficult to recognize the privileges you have that other people don’t.

For example, it feels like most of my Facebook friends are getting married and buying houses, whereas I’m nowhere near ready to buy a house. (Thanks, student loans!) I find myself getting jealous, or thinking: “Those people must have it so easy, too bad I’m stuck in an apartment.” The hypocritical part of that is: the apartment I complain about is right across the street from an RV camp full of people who are homeless. So instead of focusing on what I don’t have, I’ve learned to be more appreciative of what I do have.

How much do you have?

To help put things in perspective, there are several websites that tell you how your income compares to the rest of the world. Give them a try:

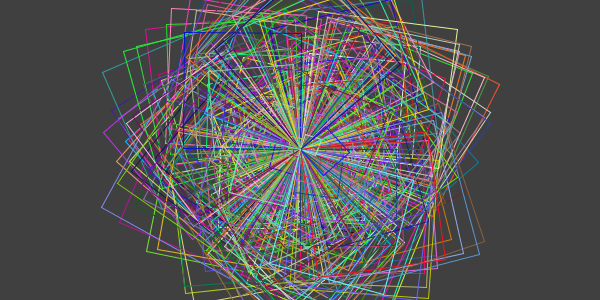

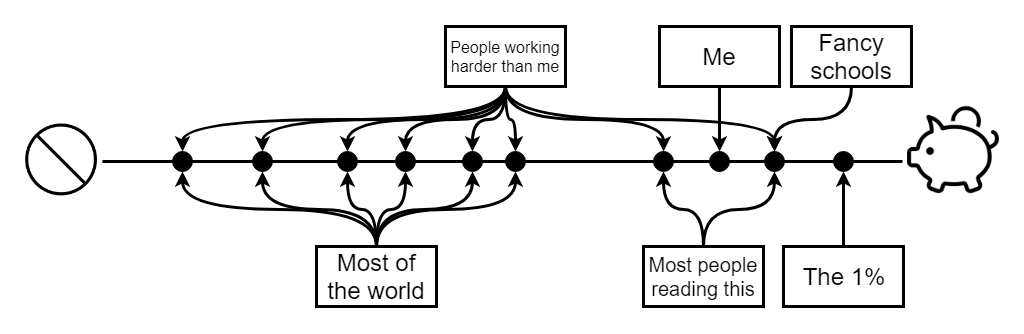

When I first saw these, I was really shocked. It’s easy to complain about not making enough money, or to compare yourself to people who have more. But at least 80% of humanity lives on less than $10 a day. The graph of the world really looks something like this:

When you think about yourself in that context, it’s easier to see how lucky, how privileged you are.

Otherism

Another realization that helped me understand my own blindspots is that humans aren’t built to empathize with people they perceive as different from them. Psychology calls this ingroups and outgroups: ingroups are the groups you think of yourself as belonging to, and outgroups are groups you think of yourself as not belonging to. It’s easier to empathize with members of groups you belong to, and it’s easier to dismiss or even dislike members of groups you don’t belong to. You can see this in everything from religion, to sports, to road rage, to internet arguments about programming languages.

I call this otherism because I think it’s at the root of most other -isms: sexism, racism, homophobia, any dismissal or hatred of somebody we view as an other.

It helps me to realize that this otherism wasn’t always necessarily a bad thing: theories in evolutionary psychology suggest that at some point in human evolution, the fear of people outside our immediate group actually helped us survive. This makes a certain amount of intuitive sense to me: back in caveman days, it was probably beneficial to protect your group, and to distrust cavemen from other groups fighting over the same resources.

The problem is, evolution moves much slower than technological progress, and that tendency towards otherism has stuck with us despite it no longer being useful. A distrust of others might have helped my great-great-great-caveman grandparents survive, but now all it does is make me more likely to fight with strangers on the internet. It also makes me prone to otherism in all its forms.

So when I recognize myself mentally dismissing or disliking somebody (or believing that somebody dislikes me), especially somebody I perceive as belonging to a different group, I ask myself: how much of this is my lizard brain talking?

The Monkeysphere

Back in 2007, David Wong explained all of the above much better than I can, in the monkeysphere article.

The monkeysphere, also called Dunbar’s number, is the idea that there’s a limit to the number of people we can have meaningful relationships with. That number is around 150 people, and it’s why you’d be sad if your friend died, but you aren’t sad if 1,000 people from the other side of the world die.

It’s also why it’s harder for us to identify with people we don’t consider a member of our ingroups. So even if somebody is making a lot of sense, if they aren’t a part of our monkeysphere, we’re probably going to ignore them.

This might not seem like it has anything to do with privilege, but it has helped me understand my interactions with other people, especially people who come from different backgrounds.

Calling Out

Humans are more likely to call out a person that belongs to another group: men are more likely to criticize women than they are to criticize other men, women are more likely to criticize men rather than other women, political party A is more likely to criticize political party B, etc. (You also get a nice self-image boost from calling somebody out, and it’s easier than working on yourself!)

This is frustrating for a bunch of reasons, and a bit pointless because humans are also less likely to honestly listen to members of other groups.

This is why men have a hard time hearing about sexism from women, and it’s why women have a hard time hearing about the struggles that men go through. I try to be mindful of my role on both sides of this: am I trying to engage with somebody outside my monkeysphere, or am I trying to focus on people inside my monkeysphere, who are more likely to hear me? On the other side, when I receive feedback, am I dismissive of information that comes from outside my monkeysphere? How can I be more receptive?

With all of that in mind, I try to resist the urge to criticize other people for seemingly not caring about the same things as me. I could spend all day arguing with people on the internet, but I’ve realized that’s just slacktivism and that my time is better spent working on myself. What’s better for the world: telling 100 random people why they’re wrong on Twitter, or asking myself how I can improve?

This is a little tricky because I do think it’s important to point out problems and to work towards improving them, but I don’t think I’m going to convince anybody to stop eating meat by lecturing them about what a bad person they are for eating a burger.

Instead, I think the way to work on problems is to first focus on yourself and the people closest to you, who are more receptive to your feedback. I highly encourage everybody to resist the urge to “call out” people outside your monkeysphere, because it reinforces the idea that you’re not in the same tribe, which actually makes it harder for anybody to improve. If you want to have that type of conversation, I’ve found it much more effective to start by welcoming the other person into your ingroup first. That’s much more work then sending out a snarky “people from group X should do blah blah blah” tweet, but it’s also much more likely to actually make a difference.

Different Perspectives

Another realization that helped me contextualize this stuff is that different people can care about the same issues for different reasons.

This might sound obvious, but I just realized this in the past couple years, and it’s helped me understand allyship more than probably anything else. It’s the idea that two people can have the same goals, but different motivations, which makes working together towards those shared goals harder than expected.

For example, only 10-20% of programmers are women. I strongly believe that this is a problem we should improve. But the way I experience this is different than the way it would be experienced by, for example, a woman who has spent her career dealing with microaggressions and the gender pay gap. For me, it’s an interesting numbers problem, it’s a puzzle that I find really fascinating. For that (hypothetical) woman, it’s a more visceral personal experience that rightfully brings with it frustration, sadness, and anger. So even though we have the same goal, when we talk about that goal, we can end up talking past one another, or even arguing.

So when I’m talking with somebody about this kind of thing, I make sure to take a second to think about: what do each of us want out of this conversation? What does this person want from me, and what do I want from them? Often the other person just wants me to listen to them, which means it’s not the right time to start talking about numbers or my own stuff.

The Limits of Caring

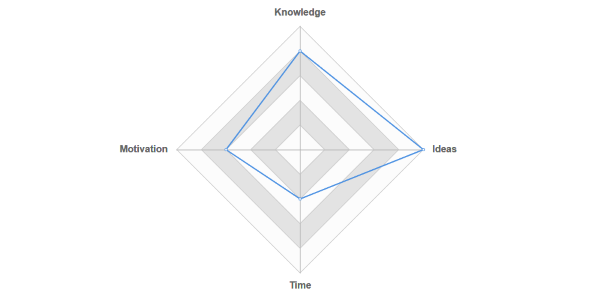

I don’t remember where I read this and I can’t find it on google now, but another thing that helped me navigate these conversations is the idea that people only have room in their brains to care about a limited number of problems. My guess is that number is around 3.

Even if I’m the most altruistic and socially conscious person on the planet, and I spend all of my time working as hard as possible to right all of the wrongs in the world, there are still only 24 hours in a day. It’s not possible to actively care about literally everything, so we have to triage what we care about.

This means there are approximately 3 issues that are particularly meaningful to me, that I work towards improving. But another person probably has their own 3 issues that are different from mine. This doesn’t make either one of us better or worse than the other. But it does mean that we might be at odds with each other when we start talking about the things that matter to us.

Whataboutism

This difference in what people care about can lead to whataboutism: the tendency to argue against caring for one thing, because what about this other thing we should be caring about instead. Here are some examples from my real life:

- How can you care about animal rights when there are homeless people?

- Why care about access to computer science instead of access to lower-paying jobs, or access to jobs that are already predominantly filled by women?

- Why talk about women in computer science without mentioning nonbinary people?

I find these kinds of arguments particularly frustrating, maybe because I generally agree with them. You’re right that I should do more for people who don’t have a home. I agree that women should be encouraged to become plumbers, and men should be encouraged to be elementary school teachers. I agree that transgender rights matter.

But none of this means that the issues I care about are less important to me, or that I should stop working to improve the things I can. And this goes both ways: it also means I shouldn’t artificially interject my own interests every chance I get, unless the other person has genuinely asked about them.

Recognizing Power

Like I mentioned above, for most of my life I didn’t feel very privileged or powerful. Surely because other people had more money, or were more senior in their career, or went to better schools, that meant I was not in a position of power, right?

Now that I work at Google, the ways I have power are a little more obvious: I help run a mentorship program, I’m an interviewer, and I’m starting to become a little (tiny bit) more senior in my career.

I try to be aware of these dynamics, and I have various approaches for keeping myself in check. For example, before I interview somebody, I spend a couple minutes asking myself a few questions: What kind of mood am I in? (I try to get myself to “neutral” so I don’t come in with a particularly good or bad attitude.) What assumptions do I already have about the person? (Even if we try to have zero assumptions, they can still creep in, and recognizing them goes a long way towards taking away their power.)

Side note: I really don’t want any of this post to come off as me giving advice, but I will say this: don’t hit on your coworkers. Don’t even think about hitting on your coworkers. Even if you mean it innocently, you’re running the risk of exploiting a power dynamic, even if you aren’t aware of it. I won’t harp on this too much, but read this Coding Horror post for more info.

Anyway, in addition to the obvious things, I’ve also started recognizing the power that I’ve always had, even before the more obvious stuff. For example, I can be a little self-conscious of the fact that I went to a college that nobody has heard of. But here’s the thing: people who look at me don’t know where I went to college. This means I can “hide” this insecurity: people I work with seem to assume that everybody else went to a big computer science school, so nobody looks at me and immediately knows that I didn’t.

This in itself is power, because plenty of other people can’t “hide” the things that make them feel like an other. I can “blend in” with the majority in a way that not everybody can. I think this is a big component of the white privilege I had trouble seeing most of my life. Society considers me “the norm” which brings with it a bunch of power, and a bunch of privilege.

So I try very hard to be aware of the space I take up. There are obvious examples, like making sure I’m not talking over people in meetings, or “passing the mic” to people who haven’t had a chance to talk yet, or not using the term “guys” to refer to groups of people. (That last one is pretty hard for me because I tend to speak pretty informally, but the best solution I have so far is to use the term “friends” instead. I’m open to other suggestions.)

I also struggle with more subtle variations of this: how do I balance working towards these goals, without taking the focus away from people who deserve it more than I do? I don’t have an answer to that one, but it’s something I think about often.

Surround yourself with people who will call you out

I recently received this advice, and it made me think. I generally consider myself pretty socially aware. I like to think I work harder than average on the issues I care about, like access in computer science. I tend to answer more questions about this stuff than I ask. I’ve thought that this must be a good sign: look how hard I’m working! Look how aware I am!

But I realized that it also means I haven’t put in enough effort to meet people who are doing the work. I was blown away when I attended CC Fest, because it was full of people who spend most of their days actively working towards the stuff that, by comparison, I only think about in my spare time.

So I’m going to try to get better at this. I’m still learning, and part of that process means I have to make myself uncomfortable more often.

With that in mind, I’d love to hear your thoughts. What was your journey? How do you think about privilege?