Ten Lessons from "Senior" Software Engineering

Ten Lessons from "Senior" Software Engineering

I’ve worked with a lot of college students who are about to enter the tech industry, so I get to have a lot of conversations about becoming and succeeding as a junior developer. But I don’t get to talk as often about going from a junior developer to a senior software engineer.

This post is my attempt at summarizing some of the lessons I’ve learned in my career so far, organized into a digestible list.

Photo by Brooke Lark on Unsplash

- Disclaimers

- My History

- 1. Ask Questions

- 2. Carve a Niche

- 3. Sell Yourself

- 4. Have an Opinion

- 5. Do Something About It

- 6. Learn to Say No

- 7. Understand People’s Motivations

- 8. Bring People with You

- 9. Be the Adult in the Room

- 10. Plan Ahead

- Don’t Worry Too Much

Disclaimers

If I’m being honest, this kind of post feels a little gross to me. I don’t like when people use their job titles as a stand-in for credibility (“google engineer says xyz so it must be true”), or when people mythologize themselves. I’ve also lost patience with lists of “productivity tips” that folks, including me, obsess over.

This post turned out to be really difficult to write. I wrote the first draft back in July, but I didn’t really like it. It came across as too “you should” and not enough “I did”. It took me three months and reading this post by Julia Evans to finally finish what you’re reading now. And I’m still not sure it’s not too self-indulgent and humble-braggy.

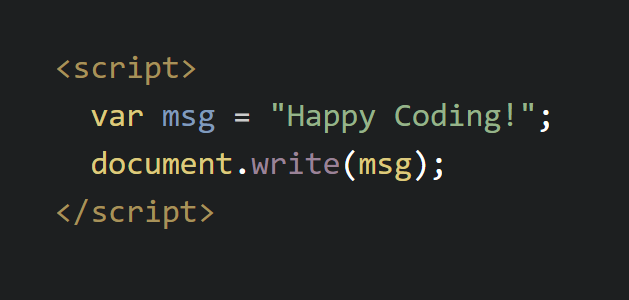

But one of my goals with Happy Coding, and with my life in general, is to improve access to the tech industry. I don’t mean that in an abstract sense: I truly believe that one of the best things I can do to improve the world is to help more people understand how the tech industry works. I learned a lot of these lessons in an environment that most people don’t have access to (like the inside of Google), so hopefully sharing it helps open those doors a bit, and maybe even helps somebody else think about their own career.

I also want to acknowledge that there are many paths through the industry, not just the path I took. And in fact, the path I took was shaped by my privilege in all its forms. I want to believe that I try to spread that privilege around, but I acknowledge that advice like “be more opinionated” might be easier said than done for folks dealing with daily microaggressions. Check out Growth and Power by Sarai Rosenberg for another take.

I’m going to focus on the positives in this post, but I also believe that the perf and promo process in big tech is pretty broken, to put it mildly. I’ll save my rant for another time, but for more info check out Why I Quit Google by Michael Lynch.

Finally, I also want to say that’s it’s totally fine to not want to grow your career. If you’re happy where you are, then I don’t think you should feel the need to climb the corporate ladder.

My History

Like I said, I don’t like when folks mythologize themselves, or when they use their job title as a shortcut to credibility. But I figure if you’re going to listen to my take on career progression, I should probably tell you what my path looked like.

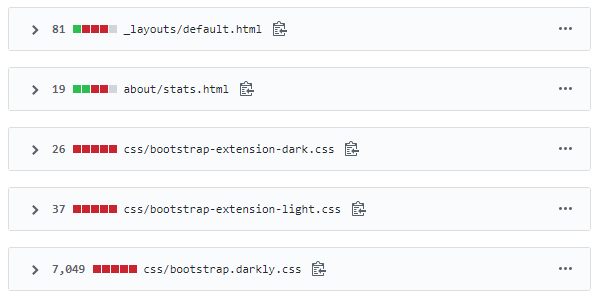

I graduated from college in December 2008, and started working for a small company that did prototype work for the FAA. To oversimply a bit, there were only two “levels” of software engineer: you were either a junior engineer or a senior engineer. On the other hand, it was a relatively small company, so I wore a bunch of different hats while I was there. I was promoted to senior engineer a couple years into my time there, but if I wanted to go “higher” than that, I either had to become a researcher or a manager. I didn’t want to do either of those things, so I happily stayed in the same place until Google called me in 2016.

When I moved to Google, I had a bit of a culture shock when I learned there were 10 different “levels” of software engineer, and also different “ladders” of job types (software engineering, product management, user experience, etc). I came from a place where I was as senior as I wanted to get, and I did a little bit of a bunch of jobs, so Google was both bigger and smaller than I was used to.

I started on a team inside Google Maps in December 2016, and in September 2019 I became the tech lead of that team. In October 2020 I was promoted to “senior” software engineer. Then in June 2021 I switched to the engEDU team, and as I write this in July October I feel like I’ve pretty successfully ramped up on my new team.

With that history in mind, I’m going to try to collect the most important lessons I’ve learned along the way, in roughly the order I learned them.

1. Ask Questions

Not knowing something that seems like it should be obvious or easy can make me feel dumb, which makes it harder for me to ask questions. I don’t want my coworkers to know how dumb I am! But here’s the lesson I’ve learned:

There’s no such thing as a dumb question, but there are dumb times to ask a question.

In other words, if I’m new to something and I have questions, the only “dumb” thing I can do is wait too long to ask those questions.

When I recently switched teams, I struggled with trying to run a server, which felt like a really “dumb” thing to be stuck on. But after a couple hours of trying different things, I gave up and asked a question in the team chat. Sure enough, I had my server running just a couple minutes later. If I had waited a week to ask somebody for help, that would have been way worse!

Photo by Amy Shamblen on Unsplash

On the other hand, I don’t ask questions as soon as I’m stuck. I usually give myself a couple hours. I also try to break problems down so that my questions are as specific as possible. Saying “I’m running this command but I’m getting this error” is more likely to get an answer than “I have no idea how to start”.

One thing I still struggle with is calling my questions dumb. “I know this is a dumb question, but…” is a habit that I’m trying to kick.

2. Carve a Niche

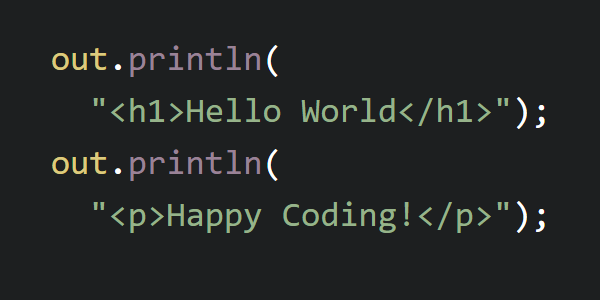

When I started my first job, I had no idea what I was doing. But I was hired to take over a project written in Java, so I quickly became “the Java guy”.

This isn’t because I was an expert in Java, it was because I was the only one with any Java experience. I found myself helping more experienced engineers get their programs running, or their IDEs set up. Nothing I was doing was super complex, but because I was the only one doing it, it quickly became “my thing” that people relied on me to do.

This has happened to me a few times, and it always happens faster than I think it will. The first bug I worked on at Google turned out to be more complicated than anybody thought it would be, but because nobody else on the team had worked on it at all, after a week I was the expert on it. I’ve had similar experiences with JavaScript at my first job, accessibility at Google, and recently UI development on my new team. It only takes a couple weeks until you have a couple more weeks of experience than anybody else.

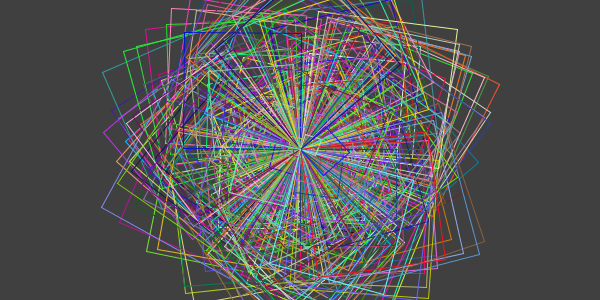

Part of this happens naturally, but recently I’ve tried to carve my niche more intentionally. Is there a bug that’s been sitting around for a while, that nobody has tried to fix yet? That’s mine now! I did exactly that when I joined my new team: as soon as I got my server running, I fixed as many accessibility bugs as I could. More recently I’ve been building the UI for our new project.

I think about carving a niche this way: when I’m cleaning my apartment, I don’t bounce back and forth between random spots, hanging up one shirt, then putting one plate in the dishwasher, then recycling one soda can. If I do that, I’ll never make any visible progress, and my apartment will stay messy. Instead, I pick a corner, and I start cleaning from there. Soon that corner is the cleanest corner in my apartment, and I slowly expand until my whole apartment is spotless.

Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

The metaphor I’m trying to make is that I think it’s important to focus on one small thing, and then build from there, rather than bouncing around between a bunch of bigger things. On the other hand, this also tends to keep me in the same place unless I actively seek out new opportunities, so I try to find the right balance.

3. Sell Yourself

I don’t know if I believe in the “it’s not what you know, it’s who you know” cliché, but I do believe in a modified version: it’s not what you know, it’s who knows you know what you know.

In other words, even if I was the best software engineer in the world, that wouldn’t help my career if nobody knew about the work I was doing. If a tree falls in a forest and nobody is around to hear it, did it make a sound?

This can be hard thanks to impostor syndrome, but I’ve tried approaching this a few different ways:

- At my first job, I had an “accolades” label to keep track of emails where somebody said something nice about me. I know how that sounds, but when it came time for performance reviews, it was much easier to go to my accolades folder than it would have been to remember that nice thing that somebody said about me six months ago. (I don’t do this at Google, mostly because Google has a separate system that lets people officially thank each other.)

- I’ve written “snippets” summarizing what I’ve done every week for the past 12 years. My first job required them for government reasons, but I’ve kept up the habit even though they’re optional at Google. I have a horrible memory, so it’s much easier to look back at my snippets when I need to summarize what I did in the past year.

- I’ve also given tech talks and demos, which are great ways to make sure that other people know what I’m working on.

- Julia Evans recommends writing a brag doc. I haven’t personally tried that, but I think it’s great advice.

To put it another way: one of the most important things to my career has been how many people know my name. I’m very uninterested in rubbing elbows with the higher ups at the golf course, but the more people who say “oh, I know Kevin, he’s the guy working on XYZ, right?” the better.

Funny enough, asking questions is one of the biggest ways I get my name out there. And they don’t even have to be technical questions! I honestly believe that most of the reason I got promoted to “senior software engineer” at Google is because a bunch of higher-ups knew I was the person who asked questions at every all-hands meeting.

4. Have an Opinion

When I first started at Google, I had an attitude of “I don’t care, I’ll work on anything!” which I thought meant that I was being helpful and flexible.

Over time, I realized it was more useful for me to have opinions. My bosses didn’t want me to tell them what the options were, they wanted me to tell them which option we should choose. Software Product Sprint didn’t need somebody to work on whatever, they needed somebody with ideas about what we should be working on in the first place. I got the tech lead position because I was the one with the strongest opinions about what we should do with the team.

I think this realization is where I started “graduating” from a junior dev to a senior dev. I’ve also found that knowing what I don’t want to work on has been just as important as (if not more important than) knowing what I do want to work on.

I’ve also found it helpful to introspect on why I feel a certain way. If I don’t want to work on a particular task, what about that task doesn’t feel right? What should we be doing instead? How can I advocate for that?

5. Do Something About It

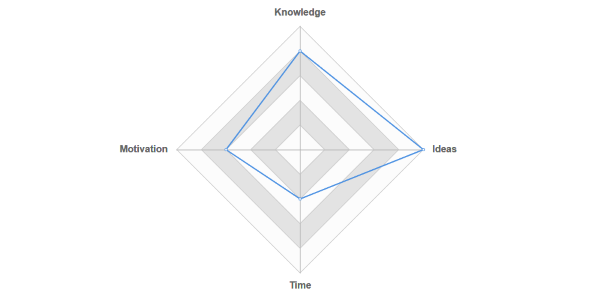

Having an opinion is a great first step to becoming a senior dev, but it’s not very useful by itself. Anybody can have ideas and opinions, but thanks to learned helplessness, not everybody wants to go further than that. But I try to think in terms of two steps:

- Step 1: Have an opinion.

- Step 2: Do something about it.

And then I ask myself, am I stopping at step one? If so, then I’m probably not being very helpful, and I think about how I can get to step two.

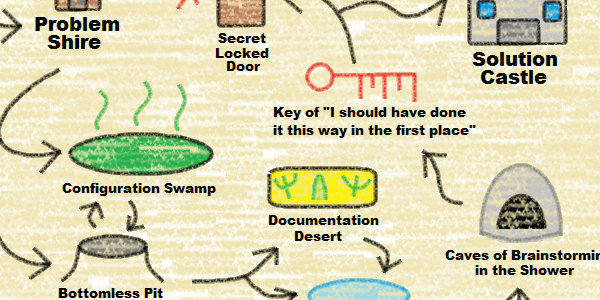

The best career advice I’ve ever received was given to me about a year after I started at Google. I was talking to my tech lead about how frustrated I was by our lack of documentation.

He replied with: “it’s your job to convince everyone else that we should spend time fixing that.”

That single sentence is the inflection point in my career that helped me understand that software engineering is much more than writing code.

I was able to convince management that we should spend time on documentation, and it became one of our main goals in the next quarter. That work led to some of my proudest technical achievements a couple years later.

6. Learn to Say No

Learning to say no is another cliché that I didn’t really understand until recently.

I thought it meant literally saying no to people, which didn’t make sense. How can I refuse to do work that my manager wants me to do, or that my team has been tasked with?

But that’s not really what it means. Saying “no” doesn’t mean literally saying no- it’s advocating for alternatives, or pushing back when priorities shift.

Let’s say my team has a task that will take us 6 months to complete, and will make our codebase much more complicated. It’s tempting to say “okay, I’ll get to work on that right away!” without thinking much more about it. But if I take a couple days to think through alternatives, maybe I can come up with a different approach that gives us 90% of the functionality, only take 3 weeks to complete, and doesn’t overcomplicate our code. Even though it’s not the original plan, suggesting that alternative is a big difference between junior and senior engineers. (This was pretty close to what happened when I worked on temporary closures on Google Maps at the beginning of quarantine.)

Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

Another rule I follow strictly is that I only work on one big project and one small project at a time. This lets me switch back and forth and make steady progress, without getting stuck in a tunnel for too long. If more work comes down the line, I pose it as a question: which of my current tasks should I stop working on in order to fit this new task in? That has been a huge improvement to not just my productivity, but also my mental health.

7. Understand People’s Motivations

Software engineering, especially when you get into “senior” software engineering, is so much more than writing code.

When I started the tech lead role, I was a little nervous: what if I don’t understand our tech stack well enough? What if somebody asks me a technical question and I don’t know the answer? But it turned out that the role was less about code and more about people. How can I convince the higher-ups that we need to spend time on something? How can I make sure another team implements a feature request we need? Are the people on my team happy? What can I do to help that?

It became really important to understand the people around me. What did they want? What were they motivated by? Who was trying to get promoted, and what did they think would get them there? Where did ideas really come from?

Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash

Understanding the answer to those kinds of questions let me craft my message, or to speak other people’s languages. For example, management on my old team kept moving engineers around to different projects. The engineers hated this, but management kept treating them as interchangeable parts. Finally, when I understood that management did this because they cared about the appearance of project velocity, I was able to convince them that the best way to improve long-term velocity is to let engineers build up ownership and expertise on the stuff they worked on. After that, everyone had a lot more continuity in their work.

8. Bring People with You

This is an extension of the last one, but it was such an important part of my approach to the tech lead role that I wanted to list it separately.

As I became more “senior” in my career, I tried harder and harder to make sure I wasn’t only looking out for myself. How can I make sure the people around me (especially people who are more “junior” than I am) are happy? That they’re being treated fairly? That their voices are heard?

One small way I try to do this is by “passing the mic” to other people. Whenever I’m in a meeting, I try to avoid answering questions that I know other people can answer, even if I know the answer myself. Instead, I try to make sure the “junior” engineers in the meeting have an opportunity to answer. “That’s a good question, and I think Engineer A has good context on that” goes pretty far.

But the first step is finding out what people want in the first place. This has been a little more difficult while working from home, but I’ve generally found that straight up asking people is a great way to start the conversation.

9. Be the Adult in the Room

Back in Google Maps, we had a problem where users were seeing generic errors like “please try again later”. As the frontend TL, I heard a lot of user complaints about this, but it was hard to debug because we had no idea which backend the error was coming from. I made it my mission to track down somebody on some backend team, any backend team really, to fix the problem.

After a couple months of me nagging anybody who would listen, a backend TL gave me this amazing advice: “sometimes you have a tendency to look for the adult in the room rather than being the adult in the room”.

And he was right.

After that, I changed my goal from finding somebody who could fix the problem, to becoming somebody who could fix the problem. This meant instead of nagging backend engineers to do something for me, I was nagging them to teach me about the system so I could do it myself. Instead of asking them to write code, I was writing code and asking them to review it. Figuring out how to fix this problem was one of my proudest technical achievements on that team.

One small way I do this day-to-day is by making a slight language adjustment: if I think we should do something, I don’t ask “should I do XYZ?” Instead I’ll say something like “I’m planning on doing XYZ. Does anybody have any qualms with me starting that?” It’s a subtle change, but it shifts ownership and makes me the adult, rather than somebody looking for an adult.

10. Plan Ahead

“Where do you see yourself in five years?” is a job interview cliché, but I think it’s an important question. I’m pretty goal-oriented, and I tend to think in terms of short term (the next few weeks), medium term (the next year), and long term (the next five years).

One example is Software Product Sprint, which I’ve worked on as my “20%” project for the past 5 years. There were times when I knew that working on it was actually bad for my short-term career, but I was okay with that because A: I loved it and B: I knew (hoped?) that it would eventually help me get my foot in the education door. Five years later, I’ve now moved to Google’s education department, and I’m starting a teaching position in January.

This also works at the team (or company) level. I like to ask myself, what should my team be working on a year from now? Does what we’re working on now get us closer to that? What are my manager’s answers to these questions? What about the rest of my team?

I also think this all ties together. When I’m trying to plan ahead, I often start over at step one and start asking questions. If I’m trying to carve a niche, I’ll try to find a niche that I know will be useful in the future (that’s one reason I took on a bunch of accessibility bugs). If I’m trying to sing my own praises, that’s easier to do if I know where leadership wants the team to be a year from now. It’s easier to have an opinion about what I’m working on this week if I know what I want to be working on a year from now, etc.

Don’t Worry Too Much

By this point, it might seem like I’m obsessed with my career and climbing the corporate ladder. I promise I’m not! I enjoy thinking about this stuff, and I do believe that “senior” software engineering is as much about people as it is about code, but I’m not really worried about any of it. I wanted to collect these into one place in the hopes of providing a window into aspects of software engineering that they don’t teach you in school, but these are lessons I’ve learned over 10+ years, not things I obsess over every single day.

So if you’ve read this far and you’re feeling like this is a bit much, don’t worry! I hope that hearing about my journey is helpful, but I also think each person accumulates their own lessons over time.

With that in mind, I’d love to hear from you. What lessons have you learned? Has any of this worked differently for you? What do you wish somebody had told you a year ago, or five years ago?