Secure Password Storage

Secure Password Storage

- Why Passwords are Useful

- Brute Force Attacks

- Hack the Gibson

- Hashing Passwords

- Brute Force Hash Attack

- Hash Lookup Tables

- Rainbow Tables

- Salting Passwords

- Peppering Passwords

- BCrypt

- Changing and Resetting Passwords

- Login Attempt Rate Limiting

- HTTPS

- Third Party Login

- Homework

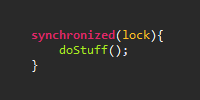

- Next: Thread Safety

If you remember nothing else from this tutorial, remember: never store user passwords directly!

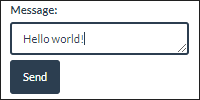

Now we know how to handle user registration and login using post requests, and we know how to use sessions to keep track of which user is making requests. If we want to allow users to register and login using a username and a password, then we have to somehow store their password when they register so that we can check the password when they login.

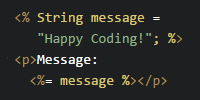

For example, we might use a utility class like this:

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

public class UserDataStore {

private static UserDataStore instance = new UserDataStore();

/**

* Map of usernames to their passwords.

*/

private Map<String, String> userMap = new HashMap<>();

public static UserDataStore getInstance(){

return instance;

}

// This class is a singleton. Call getInstance() instead.

private UserDataStore(){}

public boolean isUsernameTaken(String username){

return userMap.containsKey(username);

}

public void registerUser(String username, String password){

userMap.put(username, password);

}

public boolean isLoginCorrect(String username, String password) {

// username isn't registered

if(!userMap.containsKey(username)){

return false;

}

String storedPassword = userMap.get(username);

return password.equals(storedPassword);

}

}

This class stores usernames and passwords in a Map data structure, and then provides functions for user registration and login. We could then use this class from a RegisterServlet class and a LoginServlet class. In real life our UserDataStore class would probably use a database instead of an in-memory data structure, but for the point of this tutorial they’re basically the same thing.

Now, let’s say three users register, and our “database” (for now, just a Map data structure, but the point is the same) looks like this:

| Username | Password |

|---|---|

| Ada | password |

| Grace | correct horse battery staple |

| Stanley | tWB9,5DYq_=sv(qU |

However, we should never store passwords directly! To understand why, let’s look at it from an attacker’s point of view.

Why Passwords are Useful

First off, why do attackers want passwords in the first place? You might be thinking “my site is really small and doesn’t really have any private information in it, so what’s the big deal?”

The big deal is that most people reuse passwords. So if I’m an attacker and I get Ada’s password, here’s what I’m going to do:

- I’m going to try that username and password on email providers like Gmail, Yahoo mail, iCloud, Outlook, etc.

- If I get into somebody’s email, it’s pretty much game over. I now have access to all of their other accounts.

- I can change their passwords to something that only I know, locking them out of their own accounts.

- I can access their bank account or PayPal and steal money, login to their Amazon to buy myself some presents, or open up new credit cards in their name.

- I could login to Facebook or Twitter as them, message their friends, send out links to shady sites to try to steal more passwords, or blackmail them to get their accounts back.

Think about it this way: how would you feel if somebody had access to your email, your private messages, your photos, your bank account, and all of your other accounts? The point of this is not to scare you, but to show you that users are trusting you with their data, so you have to be very careful with it.

So, how do attackers try to get passwords?

Brute Force Attacks

If I’m an attacker and I want to get the passwords of your site, I’ve got a few options. The dumbest approach, which takes the longest, is to simply try to login with a bunch of different passwords. I can probably guess Ada’s password pretty quickly, but I probably wouldn’t be able to guess Grace or Stanley’s passwords.

If that doesn’t work, I could write a program that just tries every imaginable password. First the program tries to login with a, then b, then c, eventually aa, then ab and so on, until it finally guesses the password correctly. That takes time though: passwords that are hard to guess (passwords that are long like Grace’s or random like Stanley’s) can take hundreds (or trillions!) of years to guess.

The rest of this tutorial explains how attackers try to be smarter than the brute force approach, and how you can protect your user’s data so attackers have to fall back to the brute force approach.

Hack the Gibson

As an attacker, I don’t want to spend time on the brute force approach. So instead, I’m going to try to get at your data directly by hacking into your site.

- I could use SQL injection to get access to your database.

- I could specifically target you, the owner of the site. If I can guess your password, then I can get to your site’s data.

- I could target your site. Did you remember to change the admin password?

- I could wait for you to accidentally check a config file into your repo.

Those are just examples, but the point is that hacks like this happen all the time. Your site is public on the internet, and it will be attacked.

If you’re storing your passwords as plain text (like we are in the above UserDataStore), then all the attacker has to do is print them out. Boom, now I have the passwords of every user in your database, and I can take those to the email sites to see which ones were reused.

Hashing Passwords

To keep it very very simple, a hash algorithm is a function that converts a value (like a password) into a number. Hash algorithms are used in data structures like hash tables (HashMap is a hash table) where the hash (which is just a number) of a key is used to look up where that key’s value is stored in an array.

That might sound complicated, but a simple hash algorithm might be to just add up the order of all the letters. So a value of ABC becomes 1+2+3 = 6, and HELLO becomes 8+5+12+12+14 = 51. Let’s say we have a function called getSimpleHash() that takes a password as a parameter and returns its simple hash. Now we can use that in our UserDataStore class:

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

public class UserDataStore {

private static UserDataStore instance = new UserDataStore();

/**

* Map of usernames to their password hashes.

*/

private Map<String, Integer> userMap = new HashMap<>();

public static UserDataStore getInstance(){

return instance;

}

// This class is a singleton. Call getInstance() instead.

private UserDataStore(){}

public boolean isUsernameTaken(String username){

return userMap.containsKey(username);

}

public void registerUser(String username, String password){

int passwordHash = getSimpleHash(password);

userMap.put(username, passwordHash);

}

public boolean isLoginCorrect(String username, String password) {

// username isn't registered

if(!userMap.containsKey(username)){

return false;

}

int passwordHash = getSimpleHash(password);

int storedPasswordHash = userMap.get(username);

return passwordHash == storedPasswordHash;

}

}

Most of the logic remains the same, but now instead of storing user passwords, we’re storing hashes of their passwords. When the user tries to login with a password, we hash that password and compare it to the stored hash. If they match, then we log the user in.

After a few users register, our “database” might look like this:

| Username | Password Hash |

|---|---|

| Ada | 115 |

| Grace | 407 |

| Stanley | 424 |

Now even if an attacker gets access to our database, they won’t have access to our user passwords!

Note that our simple hash function is pretty bad: different passwords can have the same hash, and it’s fast (we’ll talk about why this is bad in a minute). But generally you wouldn’t come up with your own hash function. You’d use an existing function or a library that handles this stuff for you.

Brute Force Hash Attack

Let’s say I’m an attacker and I have a copy of your database, containing your usernames and hashed passwords. I don’t want to brute force attack your site, because sending data over the internet and waiting for a response takes a long time (especially when I’m sending thousands of requests). Instead, what I’ll do is try to guess which hash function you’re using, and then I’ll brute force attack my copy of your database.

For example, I could take the 10,000 most common passwords, run each one through your hash function (or every hash function I can think of), and then compare the result of that hash to the database. If my hash value matches any of your password hashes, then I’ve figured out that user’s password.

If that doesn’t work, then I’m back to brute force generating passwords and computing their hash values, and that still takes a very long time for good (long and random) passwords.

This is why a good password hash function is actually slow! You want it to take a long time to compute thousands of hash values, to slow down attackers. Attackers are less likely to target your site if it takes them 100 years to check enough passwords to find a match.

Hash Lookup Tables

A smarter version of the brute force hash attack is to take the 10,000 most common passwords, pass each one through the hash function, and store the result in my own table ahead of time. My table might look something like this:

| Password | Password Hash |

|---|---|

| password | 115 |

| abc | 6 |

| qwerty | 108 |

(Pretend this table has 9,997 more rows!)

Now I can take this table and very quickly check whether any of the password hashes in my table match the password hashes in your table. For each row in your table, I just check whether that password hash is in my table. If so, then I’ve found that user’s password.

Rainbow Tables

Rainbow tables are basically a more advanced version of a hash lookup table. They allow many more passwords to be stored, at the cost of having to do a little bit more work when a match is found.

To create a rainbow table, first an attacker comes up with a function that takes a hash and returns a password: note that the returned password is not the original password, as the whole point of hashes is that they aren’t reversible. Instead, the function comes up with a new password. We’ll see why in a second.

For a really simple example, let’s say the “hash reverse” function (technically these are called reduction functions, which is a pretty confusing name imho) is to take the square root of the hash, round it to 8 digits, and then map those digits to letters (1 is a, 2 is b, etc). The hash (using our simple hash function) of password is 115, the first 8 digits of the square root of 115 is 10.723805, so the generated password is JGBCHE because 10 becomes J, 7 becomes G, etc. Again, that’s just a dumb example to demonstrate the approach, but real life reduction functions aren’t much more complicated than that.

Then the attacker takes that generated password and runs it through the hash function, then takes that generated hash function and passes it through the reduction function, and passes that password through the hash function… The attacker repeats this chaining process 1,000 times, and then only stores the first password and the final hash value.

The attacker does this for, say, a million random passwords, until they have a rainbow table that looks like this:

| Start Password | End Hash |

|---|---|

| abcdef | 142 |

| monkey | 314 |

| welcome | 31 |

Now, if I’m an attacker and I have a copy of your database (containing your password hashes) and a rainbow table, here’s what I can do:

- I take a hash from your table, and I check whether it’s any of the end hashes in my table.

- If it’s not, then I send your hash through my reduction function, then I send that generated password though the hash function. I then check that hash against my end hashes. I’ll repeat that process a thousand times, or until I find a match.

- If the hash (or a newly generated hash) does match one of my end hashes, then I know that the password for your hash is in the “chain” starting with my start password.

- Now I take that start password and I start the process all over again. Each time I hash a password, I check it against your hash. If it matches, then I’ve found your user’s password.

This allows me to “store” many passwords without running out of hard drive space, because each chain represents 1,000 passwords.

It’s called a rainbow table because in real life, I’d actually have a bunch of different reduction functions, and I’d repeat the above process using each one. I’d then store the end result for each reduction function in its own column. So my table would actually look like this:

| Start Password | RF1 End Hash | RF2 End Hash | RF3 End Hash | RF4 End Hash | RF5 End Hash | RF6 End Hash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abcdef | 109 | 272 | 938 | 403 | 521 | 182 |

| monkey | 268 | 834 | 265 | 932 | 656 | 525 |

| welcome | 475 | 314 | 468 | 598 | 102 | 320 |

All of this might sound confusing, but don’t worry- you don’t really need to understand exactly how rainbow tables work. Just know that attackers can take a hash and try to figure out its password.

Salting Passwords

Creating a hash lookup table or a rainbow table can take a long time, so attackers will usually download copies of these that have already been computed for common hashing functions.

So now your goal is to invalidate those lookup tables. The best way to do that is for your users to choose more complicated passwords that are less likely to be found in precomputed tables. But users are pretty terrible at choosing good passwords, so let’s help them out.

We can help them out by coming up with a random string of characters or numbers and adding it to their passwords. We can do that in a way that the user doesn’t even know what we’re doing. For example, when a user registers, we can create a random number, append it to the end of their password, then send that new password through the hash function and store that hash. We also store the number, just like we store the hash.

Then when the user tries to login (sending us their username and their dumb password), we lookup the random number we stored, append it to the password they sent us, then send that new password through the hash function, and compare the result to the hash we stored.

That stored random number is called a salt. Here’s how we might use salting in our UserDataStore class:

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

public class UserDataStore {

private static UserDataStore instance = new UserDataStore();

/**

* Map of usernames to their password hashes.

*/

private Map<String, Integer> userPasswordMap = new HashMap<>();

/**

* Map of usernames to their salts.

*/

private Map<String, Integer> userSaltMap = new HashMap<>();

public static UserDataStore getInstance(){

return instance;

}

// This class is a singleton. Call getInstance() instead.

private UserDataStore(){}

public boolean isUsernameTaken(String username){

return userPasswordMap.containsKey(username);

}

public void registerUser(String username, String password){

int salt = getRandomSalt();

String saltedPassword = password + salt;

int passwordHash = getSimpleHash(saltedPassword);

userPasswordMap.put(username, passwordHash);

userSaltMap.put(username, salt);

}

public boolean isLoginCorrect(String username, String password) {

// username isn't registered

if(!userPasswordMap.containsKey(username) || !userSaltMap.containsKey(username)){

return false;

}

int salt = userSaltMap.get(username);

String saltedPassword = password + salt;

int passwordHash = getSimpleHash(saltedPassword);

int storedPasswordHash = userPasswordMap.get(username);

return passwordHash == storedPasswordHash;

}

/**

* Returns a random number between 0 and 1000.

*/

private int getRandomSalt(){

return (int)(Math.random() * 1000);

}

}

Now we have a getRandomSalt() function, which returns a number between 0 and 1000. When a user registers, we generate a salt for them and add that salt to their password before hashing it. We then store both the salt and the password hash. When the user tries to login, we fetch their salt, and add it to the password they sent us before we hash it, and finally we compare the resulting hash to the hash we stored at registration. Note that the user doesn’t have to know anything about what we’re doing.

Now after a few users register, our “database” looks like this:

| Username | Salt | Password Hash |

|---|---|---|

| Ada | 851 | 129 |

| Grace | 268 | 423 |

| Stanley | 547 | 440 |

We’re keeping our salts and hashes very simple just to make it easy to talk about them, but in real life a salt could be hundreds of characters long, and password hashes are similarly long strings of characters.

You might be wondering why it’s safe to store salts in the database: if an attacker gets the database, they then have the salt! But the point of salting passwords is to make it harder for attackers to look up our hashes in precomputed tables.

For example, Ada’s password of password is almost definitely in every precomputed password hash table. But the salted password of password129 might not be, and a more realistic example of passwordjAE2j8E8BvWKTxJGpO9Tm2BTwBas0WCB almost certainly isn’t.

So even if an attacker has a copy of your database, with usernames, salts, and passwords, the good news is that they can’t use precomputed tables, and they’re back to using brute force attacks.

Peppering Passwords

If you’re still not convinced that storing salt values right next to passwords is okay, then you can also append another value to each user’s password, and you can keep that value a secret if you really want to. This value is called a pepper.

In most of the above attacks, the attacker relies on getting access to your database, which in real life is separate from the code running your web app (you usually don’t just use in-memory data structures directly in your servlet code). Since in most cases an attacker won’t have access to your code, it’s actually okay to store a pepper directly as a hard-coded value. (More realistically, you’d store the pepper value in a property file, but the idea is basically the same.)

Here’s how we might user a pepper in our UserDataStore class:

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

public class UserDataStore {

private static UserDataStore instance = new UserDataStore();

/**

* Map of usernames to their password hashes.

*/

private Map<String, Integer> userPasswordMap = new HashMap<>();

/**

* Map of usernames to their salts.

*/

private Map<String, Integer> userSaltMap = new HashMap<>();

public static UserDataStore getInstance(){

return instance;

}

// This class is a singleton. Call getInstance() instead.

private UserDataStore(){}

public boolean isUsernameTaken(String username){

return userPasswordMap.containsKey(username);

}

public void registerUser(String username, String password){

int salt = getRandomSalt();

String saltedAndPepperedPassword = password + salt + getPepper();

int passwordHash = getSimpleHash(saltedAndPepperedPassword);

userPasswordMap.put(username, passwordHash);

userSaltMap.put(username, salt);

}

public boolean isLoginCorrect(String username, String password) {

// username isn't registered

if(!userPasswordMap.containsKey(username) || !userSaltMap.containsKey(username)){

return false;

}

int salt = userSaltMap.get(username);

String saltedAndPepperedPassword = password + salt + getPepper();

int passwordHash = getSimpleHash(saltedAndPepperedPassword);

int storedPasswordHash = userPasswordMap.get(username);

return passwordHash == storedPasswordHash;

}

/**

* Returns a random number between 0 and 1000.

*/

private int getRandomSalt(){

return (int)(Math.random() * 1000);

}

/**

* In real life this would probably read from a config file,

* so you could check your code into a repo without the config file.

*/

private String getPepper(){

return "this is a very long random string";

}

}

We’ve defined a getPepper() function, which returns a very long random string. We then user that value when a user registers or tries to login, exactly like we used the salt value. The difference is that we don’t store the pepper in the database.

You could take it a step further and store some number of possible pepper values. At registration time you’d choose one randomly, and at login time you’d try each one. It doesn’t take you very long to try 10 possible pepper values whenever a user tries to login, but it slows down attackers who are trying millions of passwords.

BCrypt

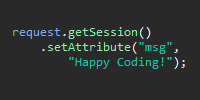

It’s important to understand all of the above, but you should also not try to come up with your own solutions. You should use an existing algorithm in an existing library. These algorithms are much more complicated than anything you’d come up with (no offense, they’re much more complicated than anything most people would come up with!), and they’ve been tested many times. I recommend using bcrypt. The bcrypt algorithm handles most of the above for you, and it has a couple of features that make our lives much easier.

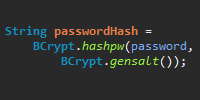

You can download a Java implementation of bcrypt called jBCrypt. That comes as a .zip file that contains a BCrypt.java file. That’s the whole library! Drop it into your project (either as a .java file alongside your source, or compile it and put it into the lib directory), and we can now use the bcrypt algorithm in our code.

To generate a salt, you can just call BCrypt.genSalt(). You can pass an optional int parameter into the BCrypt.genSalt() function, which tells bcrypt the number of rounds to use. More on that in a second.

To hash a password, you’d call BCrypt.hashpw(password, salt). The password parameter is whatever the user provided, and the salt parameter is the salt that you got from the BCrypt.genSalt() function.

The BCrypt.hashpw() function returns a hash, which actually contains a bunch of information. Here’s a small example:

String salt = BCrypt.genSalt();

System.out.println(salt); // $2a$12$Bqzq8Ow8D9LIoBSPArXWae

String hash = BCrypt.hashpw("password", salt);

System.out.println(hash); // $2a$12$Bqzq8Ow8D9LIoBSPArXWaenPXVu1MmFBmPDUvzYQw4yTPE7Rex29q

In this example, we called the BCrypt.genSalt() function with a parameter of 12. This returns a salt, but note that the salt also includes the parameter of 12. We then called the BCrypt.hashpw() function. This returns a hash, but note that the hash includes the salt. This is so we don’t have to store the salt ourselves!

Let’s take a closer look at the resulting hash:

$2a$12$Bqzq8Ow8D9LIoBSPArXWaenPXVu1MmFBmPDUvzYQw4yTPE7Rex29q

This hash actually contains 4 pieces of information:

2ais the bcrypt version. For our purposes, we don’t care about this.12is the number of rounds to use. More on that in a second.Bqzq8Ow8D9LIoBSPArXWaeis the saltnPXVu1MmFBmPDUvzYQw4yTPE7Rex29qis the hash generated by salting the password and passing it through bcrypt’s hash function.

What does the 12 mean? Basically, it tells the bcrypt algorithm how many times to hash the password. Remember how we said that password hashing should actually be slow? This parameter allows you to control how slow it is. You should do some profiling to figure out exactly how long bycrypt takes with different numbers of rounds on your server, but as a quick example, here’s how long different rounds take on my computer:

String salt = BCrypt.gensalt(12);

long start = System.currentTimeMillis();

String h1 = BCrypt.hashpw("password", salt);

long elapsed = System.currentTimeMillis() - start;

System.out.println("elapsed: " + elapsed);

| Rounds | Milliseconds |

|---|---|

| 10 | 87 |

| 11 | 167 |

| 12 | 343 |

| 13 | 654 |

| 14 | 1333 |

| 15 | 2638 |

You can use the numbers you get as a rough estimate of how long it would take to fulfill a single login attempt. You’d then choose the number of rounds that’s as slow as possible before your users start complaining. With the above numbers, I’d probably choose 12 rounds. That way it also slows down attackers. Since they’re trying thousands or millions of passwords at a time, making each attempt take longer makes it much more difficult for them. A single user of your site won’t notice if a login attempt takes a couple hundred milliseconds longer, but those milliseconds add up for an attacker who has to run the algorithm millions of times.

Anyway, now that we know how to generate a bcrypt hash, we’d just store that exactly how we stored our password hashes before. Note that we don’t have to store the rounds or the salt ourselves, as that’s built into the hash itself!

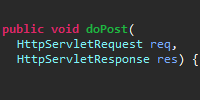

Then to check a password when a user tries to login, you can just call the BCrypt.checkpw() function:

boolean isLoginCorrect = BCrypt.checkpw(password, storedPasswordHash);

The password parameter is the password provided by the user, and the storedPasswordHash parameter is the hash we stored (by calling BCrypt.hashpw()) when the user registered.

Putting it all together, our UserDataStore class looks like this:

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

import org.mindrot.jbcrypt.BCrypt;

public class UserDataStore {

private static UserDataStore instance = new UserDataStore();

/**

* Map of usernames to their password hashes.

*/

private Map<String, String> userPasswordMap = new HashMap<>();

public static UserDataStore getInstance(){

return instance;

}

// This class is a singleton. Call getInstance() instead.

private UserDataStore(){}

public boolean isUsernameTaken(String username){

return userPasswordMap.containsKey(username);

}

public void registerUser(String username, String password){

String passwordHash = BCrypt.hashpw(password, BCrypt.gensalt());

userPasswordMap.put(username, passwordHash);

}

public boolean isLoginCorrect(String username, String password) {

// username isn't registered

if(!userPasswordMap.containsKey(username)){

return false;

}

String storedPasswordHash = userPasswordMap.get(username);

return BCrypt.checkpw(password, storedPasswordHash);

}

}

The code itself is pretty simple, and the only things that change are the registerUser() and isLoginCorrect() functions. In real life we’d use a database instead of a HashMap, but the idea is the same. And now our user passwords are safe, even if an attacker gets access to our database!

Changing and Resetting Passwords

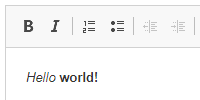

If you’re going to be storing passwords (and by passwords we mean password hashes), you need to have a way for users to change their passwords, and to reset them if they forget them.

Changing passwords is relatively straightforward. That can just be a form where a user enteres their current password and their new password. Then just hash the new password and store it like you did when they registered.

Resetting passwords is a little trickier, but you need this for users who forget their passwords. Generally you’d do this by requiring an email address when users register. When a user resets their password, you’d generated a new temporary password, store its hash in your database, and then send that password to them in an email. That allows them to login, and then force them to change their password to something they come up with.

There are a lot of considerations with this stuff, but in the interest of keeping this tutorial focused on storing passwords, I’ll leave that for a different discussion.

Login Attempt Rate Limiting

All of the above assumes that an attacker is trying to get a copy of your database that they can then attack on their own computers. But attackers could also attack your site directly, by just trying to login to your site as a user with a bunch of different passwords. They might write a program that tries to login to your site using the thousand most popular passwords. What happens if one of your users is using one of those passwords?

To prevent this kind of attack, you have to limit the number of login attempts an attacker can request from your server. One common approach is to just lock a user out after 5 failed login attempts. After they’re locked out, they either need to wait some amount of time to try again, or they need to reset their password or contact you. This is easy to implement, but it can be very frustrating for users.

Another approach is to make it so each failed login attempt takes progressively longer. The first login attempt happens in real time, the second attempt introduces a 5 second wait, and each subsequent attempt doubles the wait time. A real user will probably remember their passwords in just a few attempts, but an attacker will have to deal with exponential growth. After 10 failed login attempts, they’ll have to wait an hour and a half to attack again.

You could also limit by IP address instead of username. But note that attackers can change their IP address, and valid users can share IP addresses.

In real life you’d probably use a combination of all of the above.

HTTPS

Another way an attacker can try to get a user’s password is through a man-in-the-middle attack. Basically, this involves an attacker intercepting requests from your users and inspecting them before sending them to your server, and then inspecting your server’s response before sending it back to the user.

For example, if I’m an attacker, I can bring a wi-fi router to a public place, and setup a connection called FREE_INTERNET. I can make it so any request that goes through the router is sent to my laptop before being sent to the server. Then I just wait for people to connect to my router, and I can watch everything they do online.

This includes detecting usernames and passwords that are sent to your server. When a user logs into your server over this connection, I can just read their username and password in the logs sent from the router to my laptop.

To prevent this kind of attack, you need to setup your server so it uses HTTPS instead of HTTP. Basically, HTTPS encrypts every request so only the client and the server can understand it. Anybody else looking at it will just see a bunch of random gibberish.

How you do this depends on which server you’re using. Google is your friend here: if you’re using Elastic Beanstalk, try searching “Elastic Beanstalk HTTPS” for example.

Third Party Login

Another option is to not handle user credentials at all, and let somebody else do it for you. For example, Twitter offers this API that allows users to sign in to your website using their Twitter accounts. Many big websites offer services like this.

Start by looking into OpenID and OAuth. For example, here is a list of OAuth providers.

With this option, basically you use a library that shows a login form for whatever website your choose. The library handles the login (in a way that does not give you access to the user’s password) to the other website, and it gives you an ID that maps to the user. You can store this in your database, and use that to track your users.

You can use multiple third party logins, and you can even offer your own login as well as third party logins.

Like most things, which approach you choose really depends on how you want your site to work, as well as what your users are expecting.

Homework

- Attack your own site. Pretend to be an attacker, and research how you would attack your own site. Write a program that tries to brute-force login to your server. Take a copy of your database, and write a program that tries to determine passwords from it.

- Why should you use passwords that are long and random? Why should you not reuse passwords?

- Why should you be very careful when using public wifi connections?

- Why is it a bad idea to use the same password for multiple sites?