Linked Lists

Linked Lists

So far, you’ve learned about a lot of data structures that are built into Java: arrays, maps, sets, queues, and stacks. These are very common in interview questions, but there’s another “family” of data structure that’s not built into Java. These data structures are represented by custom objects with fields that define the relationship between data.

That might sound a little broad, but I’m specifically talking about linked lists, trees, and graphs.

This tutorial walks through the first of those: linked lists!

The Problem

Let’s say you have an ArrayList that contains 1000 elements:

List<String> list = new ArrayList<>();

for(int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

list.add(String.valueOf(i));

}

Now let’s say you want to remove the element at index 5:

int indexToRemove = 5;

list.remove(indexToRemove);

What’s the algorithmic complexity?

Removing an element from an ArrayList is linear O(n) time, because you need to shift every subsequent element to the previous index. That means if a list contains a million elements, you need to move a million elements every time you delete one single element!

Similarly, let’s say you want to insert a new element at index 3:

int indexToInsert = 3;

String valueToInsert = "this little manuever is gonna cost us O(n) time";

list.add(indexToInsert, valueToInsert);

What’s the algorithmic complexity?

Again, when you insert an element into an ArrayList, you incur linear O(n) complexity, because you need to shift every subsequent element up by an index.

You might think about using other data structures. You might use a HashSet, but they can’t contain duplicates and don’t maintain insertion order. You might use a Queue or a Stack, but they only provide access to the first and last elements.

This is where linked lists come in handy!

Nodes

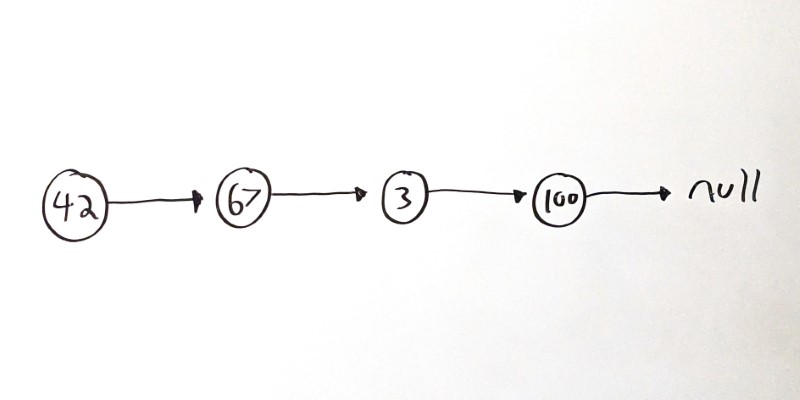

Linked lists are represented by a core object, generally called a Node. A linked list is defined by a head node, which contains a value and points to the next node.

class Node {

Node next;

Object value; // value can be int, String, etc

}

This might not look like much, but this lets you create data structures of arbitrary size, just from nodes that point to each other.

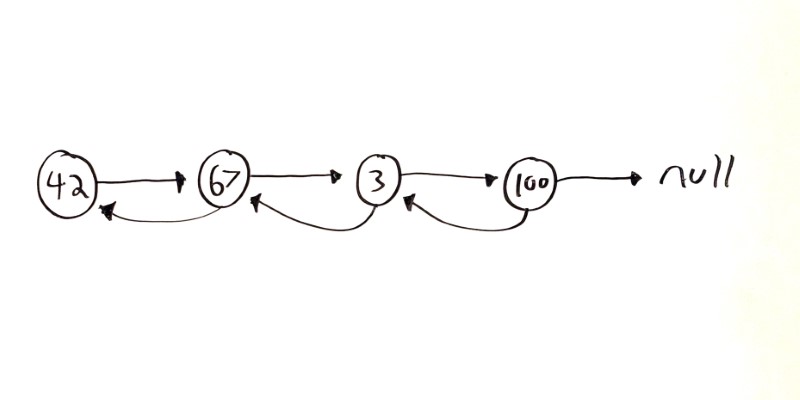

In this example, 42 is the head node, and its next value points to the node with a value of 67. That node points to the third node, which contains its own value and its own next node. That pattern continues for the whole list, until the last node (usually called the tail node) which has a next node that points to null.

Doubly Linked Lists

The above example Node class sets up a singly linked list because each node points to a single next or child node.

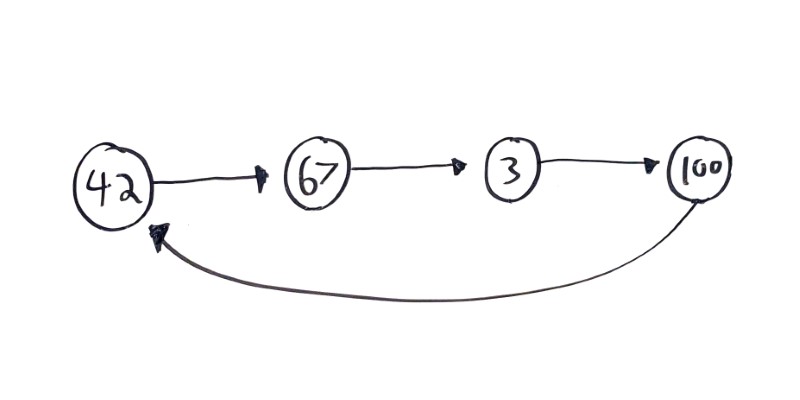

Another common pattern is for each Node to also point to its previous or parent node.

Visualizing it looks like this:

And putting it into code looks like this:

class Node {

Node next;

Node prev;

Object value;

}

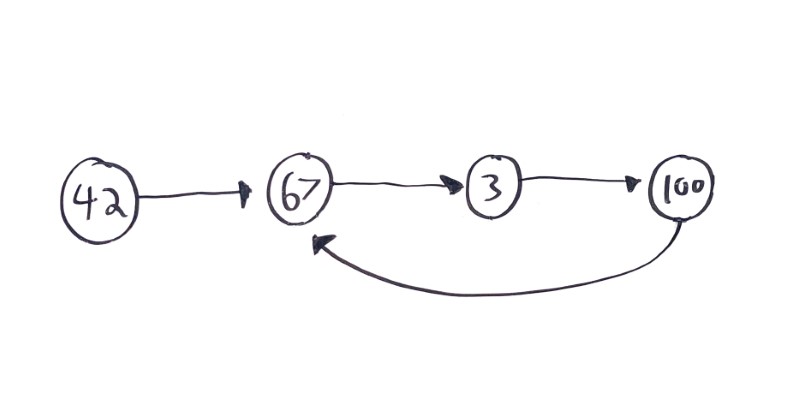

Circular Linked Lists

Circular linked lists are linked list where the tail node points back to the head node:

This can be a handy pattern, but make sure the cycle is intentional! See the Two Pointers section below for more info.

Inserting Nodes

In any case, now that you have a linked list, you can insert a new node by pointing its parent to the new node, and pointing the new node’s next to the node that was the parent’s next node.

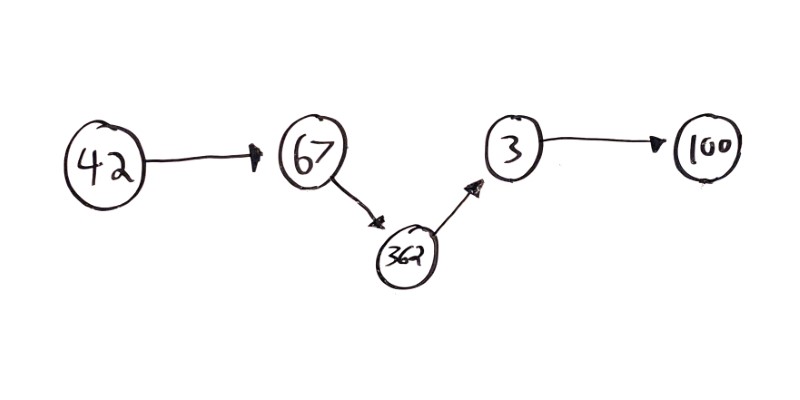

That might sound confusing, but visualizing it looks like this:

In this example, a new value 362 is being inserted between 67 and 3.

And putting it into code looks like this:

void insert(Node parent, Object newValue) {

Node newNode = new Node(newValue);

newNode.next = parent.next;

parent.next.prev = newNode;

parent.next = newNode;

}

Inserting a node is now constant O(1) time, because the only thing that changes is a couple references to next nodes.

Removing Nodes

Similar to adding a node, if you want to remove a Node, you can swap it in for its next node.

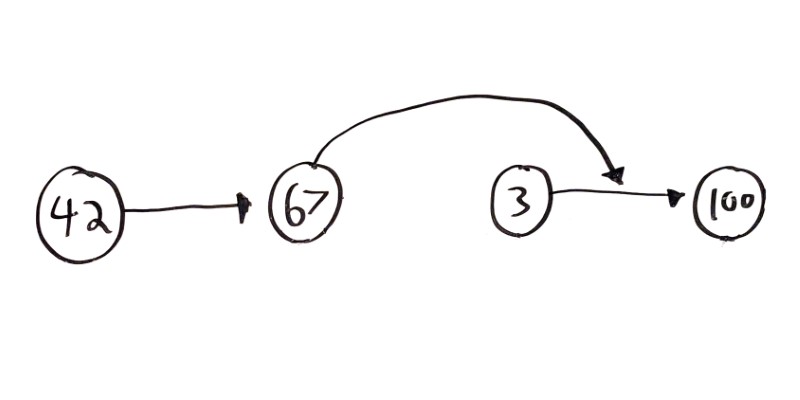

Visualizing it looks like this:

In this example, the 3 node is being removed. The only thing that needs to change is the next node that the 67 node points to!

And putting it into code looks like this:

void remove(Node node) {

Node parent = node.prev;

Node child = node.next;

child.prev = parent;

parent.next = child;

}

This assumes you have a doubly linked list. For an extra challenge, try it with a singly linked list! Hint: You can still do this in O(1) time!

Iterating

Linked lists are comprised of individual Node instances that point to each other. You can’t know ahead of time which Node will be 6th, 7th, 8th, etc, which means you can’t access a linked list by index.

(Well, you can, but it would require looping through every node until you get to that index!)

Instead, you’ll generally iterate through a linked list. That looks something like this:

// Assume you have an instance of Node

// Probably the head of a linked list

Node node;

// Loop until you get to the tail

while(node != null) {

// Do something with each Node

System.out.println(node.value);

// Iterate to the next Node

node = node.next;

}

Linked List Techniques

Linked lists are very common in technical interview questions. I think this is because linked lists require object oriented programming and work in pretty much every language.

Luckily, there are a few common patterns that come in handy when you’re working with linked lists!

Adjusting Pointers and Values

The main benefit of linked lists is that you can modify the list (inserting and removing elements) by adjusting a constant number of references.

You saw insert() and remove() above:

void insert(Node parent, Object newValue) {

Node newNode = new Node(newValue);

newNode.next = parent.next;

parent.next.prev = newNode;

parent.next = newNode;

}

void remove(Node node) {

Node parent = node.prev;

Node child = node.next;

child.prev = parent;

parent.next = child;

}

If you find yourself iterating over every node in a list and shifting a ton of values around, ask yourself if you could get away with modifying a few references!

For example, Delete Node in a Linked List challenges you to delete a node in a singly linked list, without a reference to the previous node.

You might be tempted to iterate over every node, shift each value up, and then delete the last node:

class Solution {

public void deleteNode(ListNode node) {

// Keep track of the previous node so

// so you can delete the tail node.

ListNode prevNode = node;

// Iterate over every node.

while(node.next != null) {

// Shift the next value up.

node.val = node.next.val;

// Remember the previous node.

prevNode = node;

// Iterate to the next node.

node = node.next;

}

// At this point, prevNode points to the

// tail node's parent. This deletes the

// tail node, which is no longer needed.

prevNode.next = null;

}

}

This is exactly what you’d do if you were working with arrays! But this incurs a linear O(n) complexity, because it iterates over the entire list.

Instead, you can “think in linked lists” and change two references:

class Solution {

public void deleteNode(ListNode node) {

node.val = node.next.val;

node.next = node.next.next;

}

}

Now this is constant O(1) time, because no matter how long the list is, you’re only doing a constant amount of work!

Recursion vs Iteration

That being said, there are plenty of problems where you need to iterate over every element in a linked list. Tasks like finding a particular node or value, reversing a linked list, or detecting cycles all require iterating over the linked list.

Depending on the problem, you might iterate over the list with a while or for loop, or you might use recursion.

For example, let’s say you wanted to write a function that determines whether a linked list contains a value.

Here’s an iterative approach:

boolean linkedListContainsValue(Node node, Object value) {

while (node != null) {

if(node.value == value) {

return true;

}

node = node.next;

}

return false;

}

This function uses a while loop to iterate over every node in the linked list, until it finds one with the target value. If the while loop exits, that means no node contains the value, so it returns false.

And here’s the same function, this time using recursion:

boolean linkedListContainsValue(Node node, Object value) {

if (node == null) {

return false;

}

if (node.value == value) {

return true;

}

return linkedListContainsValue(node.next, value);

}

This recursive function sets up two base cases: if node is null, that means the function recursed off the end of the list without finding the value. If the node’s value is the target, then we’ve obviously found the value. Otherwise, the function recursively calls itself with the next node in the list.

Similar to what we discussed in the recursion tutorial, choosing between recursion and iteration often comes down to personal preference and how your brain organizes information. Keep both approaches in mind as tools you might use to solve problems!

Two Pointers

Back in the arrays tutorial we talked about a technique that involved using two indexes to iterate through an array instead of relying on a single index. This comes in handy for searching through and processing an array in a single pass, instead of needing to iterate multiple times. In other words, two pointer techniques let you process an array in linear O(n) time instead of quadratic O(n ^ 2) time.

You can use a similar approach with linked lists!

For example, there’s a common problem of cycles in linked lists, where a node’s next variable points to a previous node:

Cycles are a problem for linked lists, because they mean iterating over the list will never exit. How would you detect a cycle?

You might add a boolean visited property to your Node class, and set it to true as you iterate. If you get to a node with a visited property that’s already true, then you’ve detected a cycle.

boolean containsCycle(Node node) {

while(node != null){

if(node.visited){

return true;

}

node.visited = true;

node = node.next;

}

return false;

}

But what if you couldn’t modify the underlying data structure?

You might also use another data structure, like a HashSet that contains the nodes you’ve visited. If you get to a node that’s already in the HashSet, then you’ve detected a cycle.

boolean containsCycle(Node node) {

Set<Node> visited = new HashSet<>();

while(node != null){

if(visited.contains(node)){

return true;

}

visited.add(node);

node = node.next;

}

return false;

}

But what if you couldn’t create any extra data structures?

Instead, you could use two pointers that move through the linked list at different speeds: one slow, and one fast. If the fast pointer ever “laps” the slow pointer and reaches it again, then you know there’s a cycle!

public boolean hasCycle(Node head) {

// slow moves one node at a time

Node slow = head;

// fast moves two nodes at a time

Node fast = head.next.next;

// iterate until fast falls off the end of the list

while(fast != null && fast.next != null){

// if fast catches up with slow, list contains a cycle

if(slow == fast){

return true;

}

// move by one node

slow = slow.next;

// move by two nodes

fast = fast.next.next;

}

// if the loop exits, no cycle was found

return false;

}

This runs in O(n) time, and does not require modifying the underlying data or relying on any other data structures!

More formally, this is called Floyd’s cycle-finding algorithm, but the overall idea of using two pointers applies to many problems!

Built-In Data Structures

Earlier, I said that linked lists are not built into the language, but rather rely on objects like the Node class.

That’s mostly true in the context of interviewing, because many questions are based on manipulating nodes directly. But it’s also an oversimplification!

Java does contain a few linked list data structures:

LinkedList uses an internal Node class to provide efficient insertion and deletion.

If you read the documentation for Java’s LinkedList class, you might expect the add(int index, E element) and remove(Object o) functions to provide efficient insertion and deletion. But that’s wrong!

Those functions do not run in constant O(1) time. They run in linear O(n) time! What’s going on?

It turns out that those functions really do two things: first, they iterate to the correct node, and then they perform the insertion or deletion. The insertion or deletion by itself is constant O(1) time, but the iteration costs linear O(n) time.

The benefits of Java’s LinkedList class are best taken advantage of in conjunction with another class: ListIterator.

For example, let’s say you wanted to take in a List of String values, and insert "world" after every occurrence of "hello" in the list.

void addWorld(ArrayList<String> list) {

for(int i = 0; i < list.size(); i++) {

String word = list.get(i);

if(word.equals("hello")) {

list.add(i + 1, "world");

}

}

}

What’s the algorithmic complexity?

This code iterates over the entire list, and then for each element it potentially calls list.add(i + 1, "world") which internally shifts every subsequent element to the next index. That gives the whole function an algorithmic complexity of quadratic O(n ^ 2) time!

Here’s the same thing with a LinkedList and a ListIterator:

void addWorld(LinkedList<String> list) {

ListIterator<String> iterator = list.listIterator();

while(iterator.hasNext()) {

String word = iterator.next();

if(word.equals("hello")) {

iterator.add("world");

}

}

}

Now the code uses a ListIterator to iterate over the entire list, and it calls iterator.add("world") which relies on the underlying efficiency of the LinkedList class. This gives the whole function an algorithmic complexity of linear O(n) time!

Java also contains other classes that rely on linked lists behind the scenes. Specifically, LinkedHashSet and LinkedHashMap both use a linked list to maintain insertion order.

These data structures can come in handy in interviews, but it’s more common to be asked to work with nodes directly!

Practice Problems

- Delete Node in a Linked List

- Removed Linked List Elements

- Linked List Cycle

- Linked List Cycle II

- Remove Nth Node From End of List

- Merge Two Sorted Lists

- Merge k Sorted Lists

- Swap Nodes in Pairs

- Reverse Nodes in k-Group

- Rotate List

- Remove Duplicates from Sorted List

- Remove Duplicates from Sorted List II

- Partition List

- Reverse Linked List

- Reverse Linked List II

- Intersection of Two Linked Lists

- Odd Even Linked List