Dynamic Programming

Dynamic Programming

You’ve seen recursion in technical interviewing, which is a technique where a function calls itself. Recursion is handy, because it lets you break a problem down into smaller problems. Those smaller problems are often easier to solve than the original problem!

However, recursion has a potential downside: if the smaller problems you’re solving are identical to each other, you can end up repeating the same calculation many times, which is inefficient.

This article talks about dynamic programming, which is a technique for remembering those smaller calculations so that you can avoid repeating work.

Demystifying Dynamic Programming

Dynamic programming is often associated with complex algorithms, but at its core is a reasonable goal: breaking a problem down into smaller overlapping steps, and then storing the result of those steps so you can avoid repeating work.

The term “dynamic programming” itself doesn’t really mean anything. Its inventor Richard Bellman has said that he chose it mostly to sound impressive:

I was interested in planning, in decision making, in thinking. But planning, is not a good word for various reasons. I decided therefore to use the word “programming”. I wanted to get across the idea that this was dynamic, this was multistage, this was time-varying. I thought, let’s kill two birds with one stone. Let’s take a word that has an absolutely precise meaning, namely dynamic, in the classical physical sense. It also has a very interesting property as an adjective, and that is it’s impossible to use the word dynamic in a pejorative sense. Try thinking of some combination that will possibly give it a pejorative meaning. It’s impossible. Thus, I thought dynamic programming was a good name. It was something not even a Congressman could object to. So I used it as an umbrella for my activities.

The name has lived on, but the important thing to remember is that “dynamic programming” really means breaking a problem down into small steps, looking for places where those steps overlap, and storing results to avoid repeating work.

Example: Fibonacci

The Fibonacci sequence is a sequence of numbers, where each number is the sum of the previous two numbers.

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610, ...

The sequence starts with 0 and 1, and then every other number is the sum of the previous two numbers. 0 + 1 = 1, 1 + 1 = 2, 1 + 2 = 3, 2 + 3 = 5, 3 + 5 = 8, etc.

You can calculate the nth Fibonacci number using a recursive function:

public int fibonacci(int n) {

// The 0th and 1st Fibonacci numbers are 0 and 1.

if(n == 0 || n == 1) {

return n;

}

// Every other Fibonacci number is the sum of the previous two Fibonacci numbers.

return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2);

}

This code calculates fibonacci(n) by calculating fibonacci(n - 1) and fibonacci(n - 2) and then adding them together. The first two Fibonacci numbers (0 and 1) are the base case, and every other calculation is a result of adding the previous two results.

What’s the algorithmic complexity of this function?

You might be tempted to say it’s O(log n) like binary search, or O(n log n) like merge sort, because those are both recursive functions.

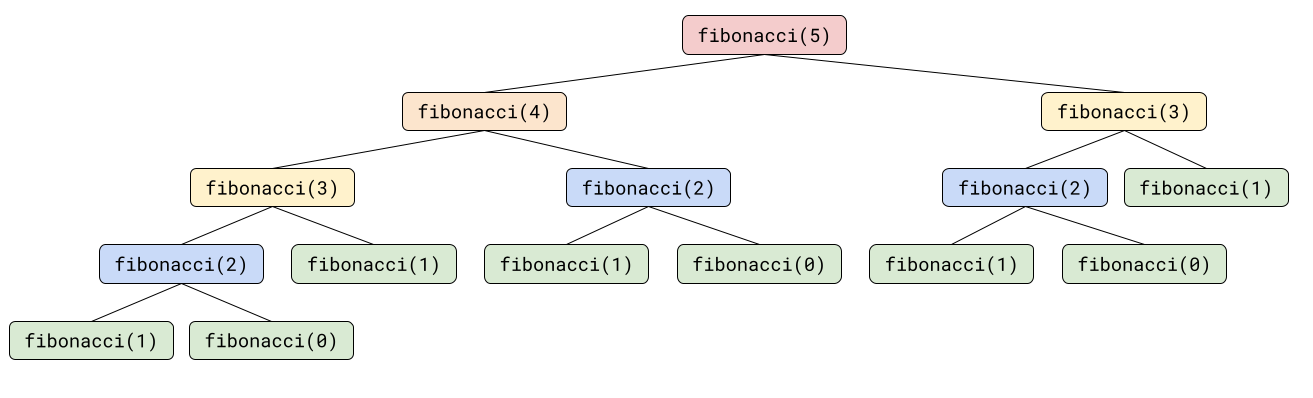

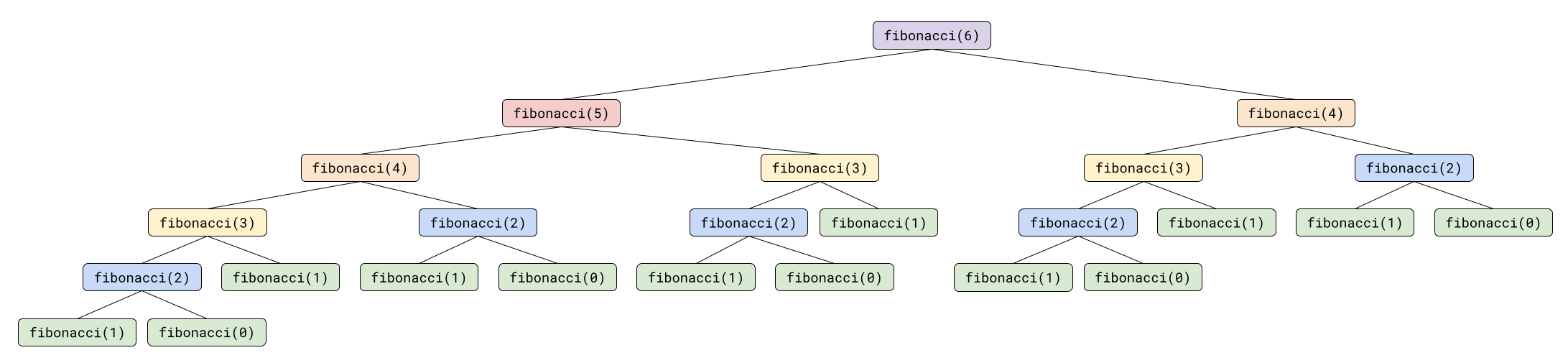

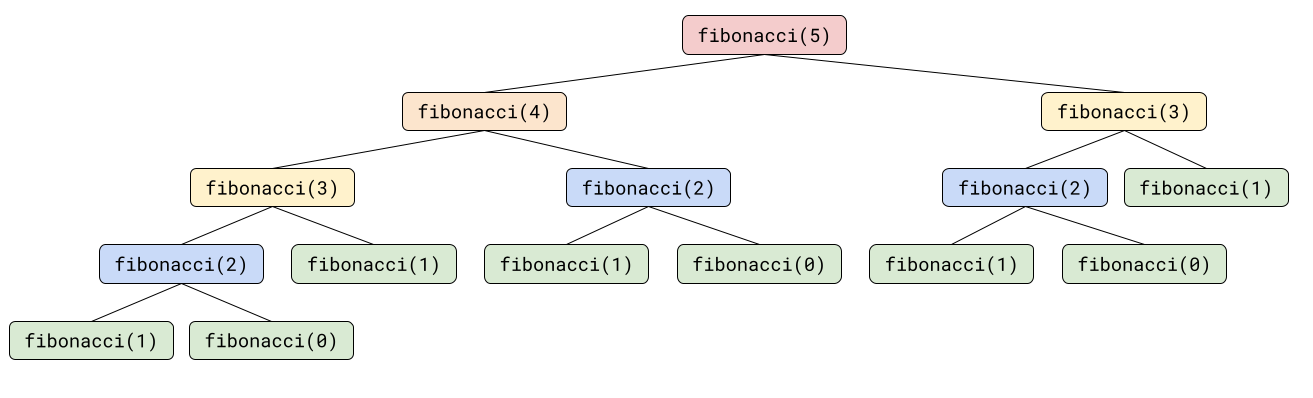

But think about the recursive call stack for fibonacci(5):

To calculate fibonacci(5), you need to calculate fibonacci(4) and fibonacci(3). But to calculate fibonacci(4), you need to calculate fibonacci(3) and fibonacci(2). And to calculate fibonacci(3), you need to calculate fibonacci(2) and fibonacci(1), and so on. So fibonacci(5) ends up making 15 recursive calls to itself!

Now think about what happens if you increase the input by 1. How many recursive function calls does fibonacci(6) make?

To calculate fibonacci(6), you need to calculate fibonacci(5), and you also need to calculate fibonacci(4). So going from an input of 5 to an input of 6 increases the number of recursive calls from 15 to 25. You can count the recursive calls for various input sizes:

n |

fibonacci(n) recursive calls |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 15 |

| 10 | 177 |

| 20 | 21,891 |

| 30 | 2,692,537 |

| 40 | 331,160,281 |

| 50 | 40,730,022,147 |

| 60 | 5,009,461,563,921 |

| 70 | 616,123,042,340,257 |

| 80 | 75,778,124,746,287,800 |

| 90 | 9,320,093,220,751,060,000 |

| 100 | 1,146,295,688,027,630,000,000 |

The number of required recursive calls almost doubles every time n increases by 1. This makes the algorithmic complexity O(2 ^ n), which means the runtime will double every time n increases by 1.

Side Note: Math Corner

The complexity of O(2 ^ n) is a good enough approximation for the above recursive function. But the real bound has an interesting property that I’m calling out because I think it’s neat!

The number of recursive calls that fibonacci(n) makes is equal to the number of recursive calls that fibonacci(n - 1) makes, plus the number of recursive calls that fibonacci(n - 2) makes. And the number of recursive calls that fibonacci(n + 1) makes is equal to the number of recursive calls that fibonacci(n) makes, plus the number of recursive calls that fibonacci(n - 1) makes.

In other words, increasing n by 1 increases the number of recursive calls by fibonacci(n - 1).

Going from fibonacci(n) calls to fibonacci(n) + fibonacci(n - 1) is slightly less than double. But if it’s not double, what is it?

Fibonacci numbers have a property, where the ratio of fibonacci(n) to fibonacci(n + 1) approaches a specific number as n increases. That specific number is roughly 1.618, and it’s also known as the golden ratio. The golden ratio is so common that it has its own symbol: φ (phi).

So the “real” algorithmic complexity of the above recursive fibonacci() function is O(φ ^ n). This means that as n increases by 1, the runtime will increase by a factor of φ.

You don’t really have to remember that, I just thought it was cool.

Dynamic Programming to the Rescue

Whether the algorithmic complexity is O(2 ^ n) or O(φ ^ n), either way the runtime increases exponentially as n gets bigger.

This is very slow! On my computer, fibonacci(50) takes about a minute, fibonacci(51) takes about 2 minutes, and fibonacci(52) takes about 5 minutes. I got sick of measuring at that point, but at that rate, calculating fibonacci(100) would take about… 40,000 years. 😱

Can you improve it?

Take another look at the diagram of the recursive calls that fibonacci(5) makes:

To calculate fibonacci(5), you need to calculate fibonacci(4) and fibonacci(3). But to calculate fibonacci(4), you need to calculate fibonacci(3) and fibonacci(2). And to calculate fibonacci(3), you need to calculate fibonacci(2) and fibonacci(1), and so on.

The algorithm ends up calculating the same thing multiple times. It calculates fibonacci(3) twice, and fibonacci(2) three times. And it gets much worse for larger values of n!

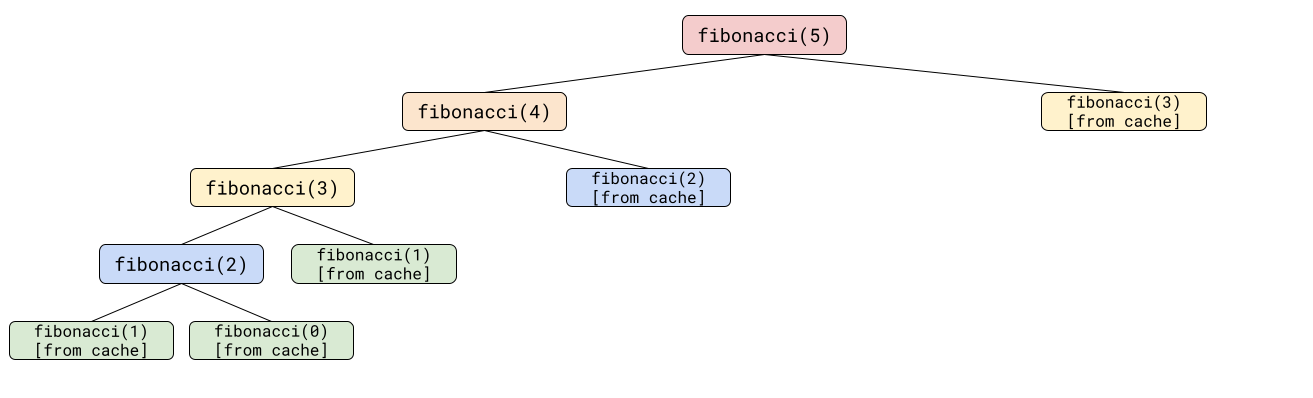

To avoid all of that repeated work, you could cache the results. Then before you make a recursive call, you could check the cache. If the cache already contains the result, you can return that instead of going through the rigmarole of calculating it again.

The approach of caching the results is also called memoization.

The code looks like this:

Map<Integer, Integer> cache = new HashMap<>();

{

cache.put(0, 0);

cache.put(1, 1);

}

int fibonacci(int n) {

if(cache.containsKey(n)) {

return cache.get(n);

}

int result = fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2);

cache.put(n, result);

return result;

}

Now what’s the algorithmic complexity?

Think about what the recursive call stack looks like now:

Now, instead of recalcluating fibonacci(3) twice, the code calculates it once, and then gets it from the cache if it needs it again.

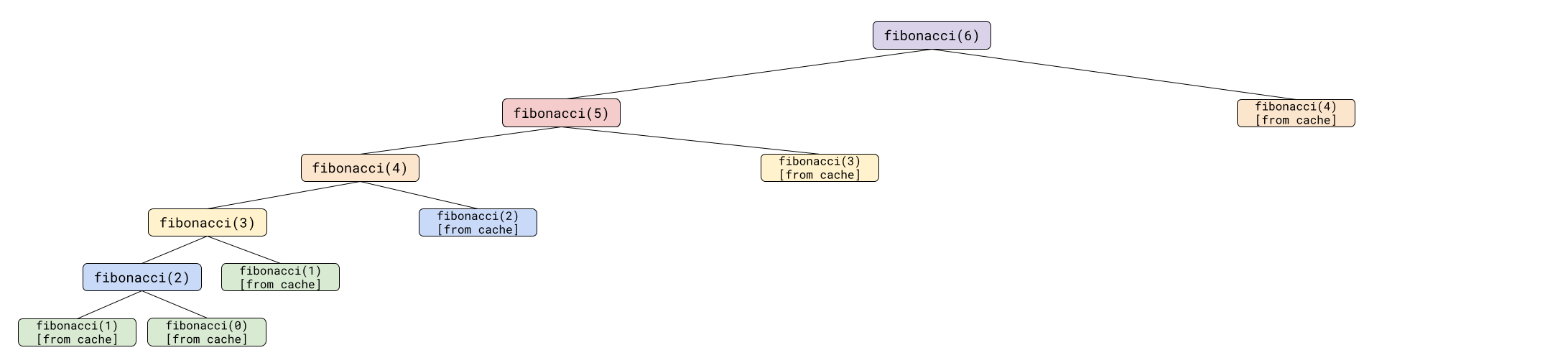

Increasing n from 5 to 6 looks like this:

Because previous results are cached, increasing n now increases the runtime by a constant factor. That makes the dynamic programming version of the recursive fibonacci() function O(n).

That’s a huge improvement! Calculating fibonacci(100) now takes about 0.000007 seconds on my computer. That’s a little better than 40,000 years!

Bottom-Up vs Top-Down

The above dynamic programming version of the recursive fibonacci() function works by trying to calculate fibonacci(n), and then breaking that down into fibonacci(n - 1) and fibonacci(n - 2), and so on.

This is a top-down approach, because it starts at the desired end state, and then works its way down to known values (in this case, fibonacci(0) and fibonacci(1)).

You can also use a bottom-up approach with dynamic programming, where you start with the smaller problems and work your way towards the desired end state.

The code for the bottom-up approach looks like this:

int fibonacci(int n) {

Map<Integer, Integer> cache = new HashMap<>();

cache.put(0, 0);

cache.put(1, 1);

for(int i = 2; i <= n; i++) {

int result = cache.get(i - 1) + cache.get(i - 2);

cache.put(i, result);

}

return cache.get(n);

}

This code is specific for the Fibonacci problem, but the important part to remember is the overall pattern of creating a cache from a known starting point and building it up towards the desired end state.

Because the Fibonacci problem only ever cares about the most recent two numbers, you can further shorten the code:

int fibonacci(int n) {

if(n == 0) {

return 0;

}

int previousValue = 0;

int currentValue = 1;

for(int i = 2; i <= n; i++) {

int result = previousValue + currentValue;

previousValue = currentValue;

currentValue = result;

}

return currentValue;

}

There’s a debate to be had about whether this solution “counts” as dynamic programming. But the point to these approaches is not to be pedantic and prescriptive, it’s to have a set of tools that you can use to solve problems. So don’t worry about whether a particular approach counts as dynamic programming. Instead, remember the technique of splitting a problem down into smaller steps and then caching the results of those smaller steps so you don’t have to repeat the same calculations over and over again.

Practice Questions

- Modify the above Fibonacci examples to avoid integer overflow issues.

- Binary Search

- Sort an Array

- Climbing Stairs

- Integer to English Words

- Elimination Game

- Fibonacci Number

- Power of Two

- Predict the Winner

- Generate Parentheses