History

History

- Ancient History

- BC: Before Computers

- From Theory to Reality

- The Golden Age of Algorithms

- The Art of Computer Programming

- Up Hill Both Ways

- Taking It Personally

- Interviewing

- The Interviewing Arms Race

- The Next Generation

- More Info

Data structures and algorithms can be intimidating, and their relationship with technical interviews can make the process feel even more daunting. But I think understanding the history of data structures and algorithms, and how they’ve been used in interviews over time, can help them feel more approachable.

With that in mind, this page contains a brief history of data structures, algorithms, and tech interviews.

Ancient History

Believe it or not, algorithms are old. Really old.

Algorithms are step-by-step processes, and you probably use them every day. Recipes, driving directions, and furniture assembly instructions can all be thought of as algorithms. They’re step-by-step processes that you follow to accomplish a goal, which is what an algorithm is. With that framing, algorithms have been around since pretty much the beginning of humanity.

More formally, algorithms have been used in math for thousands of years. Ancient Babylonian, Egyptian, Indian, and Greek mathematics were all developed before the year zero, and they all contained step-by-step processes, or algorithms.

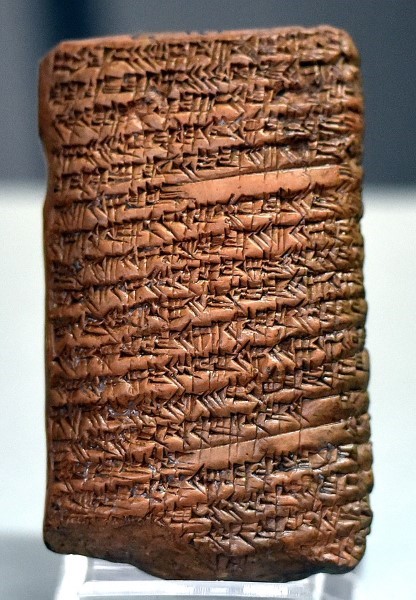

Clay tablet from ancient Babylonia showing mathematical algorithms

The term algorithm itself comes from a Persian mathematician named Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī. Back in the 9th century, he popularized an approach for doing math that we still use today: by writing numbers in decimal notation (as opposed to older notations like Roman numerals) and then applying step-by-step processes to them (like adding, subtracting, etc). This approach to math is called algorism, and it originally came from a translation of his name.

From algorism, we got the more general term algorithm, which refers to any step-by-step process, especially in computation.

I could go down etymological rabbit holes all day, but the main takeaway is that algorithms are very old, and historically referred to any step-by-step process, especially in math.

BC: Before Computers

At the risk of going down another etymological rabbit hole, the term computer originally referred to people who did math by hand, long before modern calculators and computers existed. Throughout history, human computers used physical devices to help with their calculations: think of abacuses and slide rules.

In the 1600s, mechanical calculators were invented and subsequently improved. These survived until quite recently- you can still sometimes see them used as cash registers!

Mechanical calculator

In the 1800s, mechanical calculators began to evolve into what we think of as computers today. Charles Babbage designed a set of machines called the analytical engine that improved on traditional mechanical calculators because it could not only do one math operation at a time, but could be programmed using punch cards to take the output of one operation and feed it into a new operation. The analytical engine supported many of the computational features we now take for granted: input / output, looping, and branching.

Ada Lovelace took an interest in the analytical engine, and translated an article on the topic from French to English. In the notes for that translation (which ended up being three times longer than the original article), she wrote an example algorithm that used the analytical engine to calculate Bernoulli numbers. This is generally considered the first computer algorithm.

Ada Lovelace, the first computer programmer!

The analytical engine is important because it helped shift the possibilities of technology, from simple mechanical calculators to more advanced computational devices. However, the analytical engine itself was never actually built! The design for it existed, but building it was too complicated and expensive for the time. Even today, it has still never been built.

Despite the analytical engine never being built, Charles Babbage predicted the subsequent obsession with algorithmic efficiency:

“As soon as an analytical engine exists, it will necessarily guide the future course of the science. Whenever any result is sought by its aid, the question will then arise—By what course of calculation can these results be arrived at by the machine in the shortest time?” - Charles Babbage

So the dreaded interview question of “can we make this algorithm more efficient?” dates all the way back to before the first computer existed!

From Theory to Reality

The late 1800s and early 1900s saw progress in both math and engineering, and mechanical computers became more advanced. But they were still designed for very specific tasks, like predicting tides for ship navigation or calculating long-range ballistics for artillery targeting. They were also still analog, and “reprogramming” them meant physically rewiring them every time you wanted to use them for a different task.

In 1936, Alan Turing invented a theoretical device that he called an “automatic machine” or an “a-machine”, but that we now call a Turing machine. Turing machines are a way of thinking about math as a combination of data and instructions. With this framing, Turing machines are no longer limited to specific tasks- they can do anything that you can represent as data and step-by-step instructions. In other words, they can do anything that you can represent as an algorithm.

The existence of machines with this property has the important consequence that, considerations of speed apart, it is unnecessary to design various new machines to do various computing processes. They can all be done with one digital computer, suitably programmed for each case. - Alan Turing

Alan Turing

World War 2 increased interest and investment in computer technology. Early computers were used for tasks like calculating bomb trajectories, simulating physics for Project Manhattan, and breaking encrypted messages.

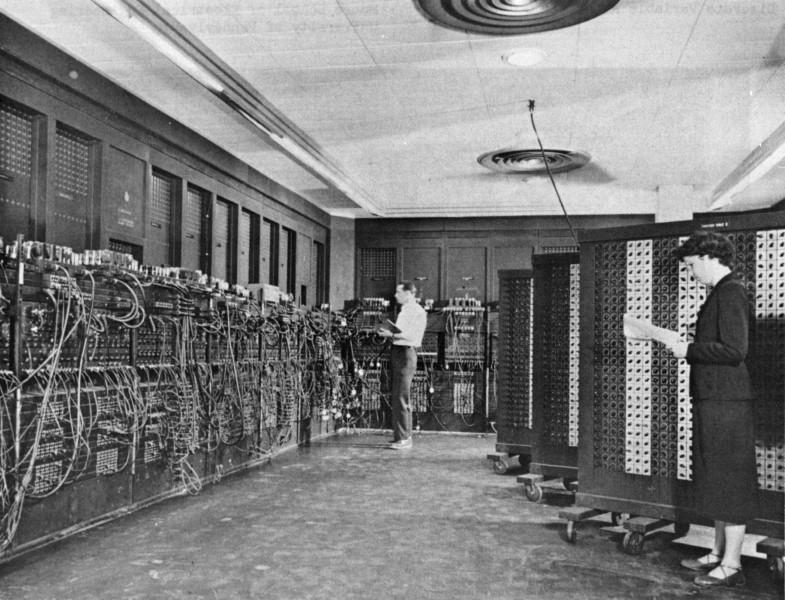

At this point, computers were still analog, took up entire rooms, and had cool names like Collosus and ENIAC. You didn’t really “program” these computers- they were designed for a particular task, and getting them to perform a different task still involved physically rewiring them.

ENIAC, an early computer that took up an entire room

Towards the end of the war, in 1945 John von Neumman wrote a paper that built on Alan Turing’s ideas to describe an approach for computers to treat instructions (which up until this point had been physical connections) the same way they treated data (which was stored in early forms of what we’d now call memory).

This was a huge conceptual shift. Now instead of building a new computer for each specific task we needed to do, a single computer could take in instructions to perform any task.

If all of this sounds familiar, that’s because this is how every modern computer works! Modern devices use a system that’s now called the von Neumman architecture, and almost every modern programming language is considered Turing complete.

After the war, the next generation of computers was built with the von Neumman architecture. Then from mainframes that took up entire rooms, we got personal computers, and finally the ubiquitous devices we have today.

The Golden Age of Algorithms

Like I said above, algorithms have been around forever, from the first time a proto-human followed a step-by-step process to accomplish a goal. More formally, they’ve been used in math throughout the centuries.

But the von Neumman architecture meant that now instead of designing an entirely new physical device every time a new problem emerged, computer scientists could focus on the instructions that they gave these more general-purpose computers. These instructions could be published, shared, and reused, which kicked off a golden age of algorithm development.

In the 1950s and 1960s, many algorithms we study today were developed. Merge sort was invented by John von Neumman himself! Data structures like arrays, hash maps, linked lists, binary search trees, and stacks were also developed during this time.

The Art of Computer Programming

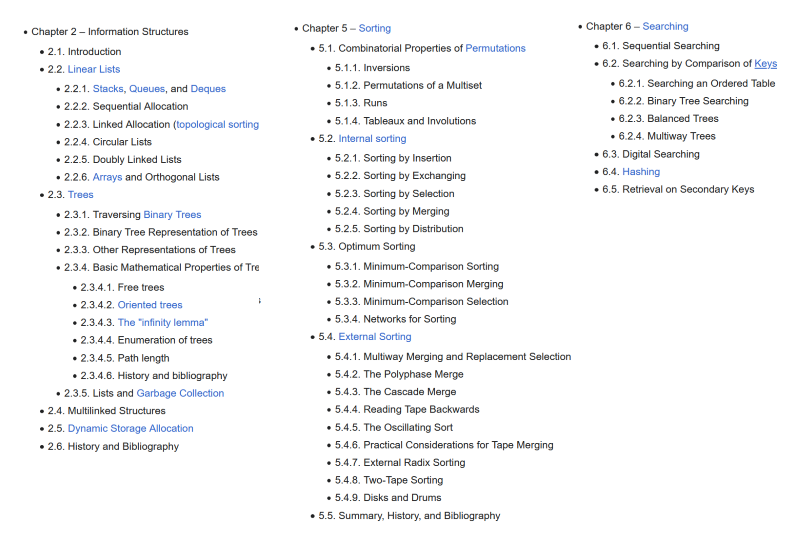

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Donald Knuth released a series of books that are collectively called The Art of Computer Programming. These books described the data structures and algorithms that had been developed during the preceding 20+ years.

Donald Knuth coined the phrase “analysis of algorithms” and also popularized the idea of using asymptotic analysis, aka big O notation to talk about algorithmic efficiency.

A few years later, Niklaus Wirth wrote a book called Data Structures + Algorithms = Programs, which took the concepts from The Art of Computer Programming and made them more accessible, particularly in education.

Chapters from The Art of Computer Programming by Donald Knuth

These books influenced an entire generation of programmers and defined the way we study data structures and algorithms today. Reading through their chapter outlines is like reading the syllabus of any modern data structures and algorithms course!

Up Hill Both Ways

Think about what programming looked like in these early days. Computers were large and expensive, and usually shared between multiple people. Entire companies, or entire university computer science departments, might have had a single computer that everyone shared!

That meant that writing and running a program was a long process. First, you wrote your code out by hand, doing your debugging in your head. After you had a hand-written program that you thought would work, then you typed it onto a series of punch cards: one punch card for each line of code. Then you’d take your punch cards to the shared computer, where you often had to wait in line behind other people running their own programs. If your program didn’t work, you’d have to start the process all over again.

Punch card representing a line of Fortran code: Z(1) = Y + W(1)

Although the process of writing, running, and debugging code has gotten much easier, a lot of the mentality required in these “golden years” survives today. Writing code by hand, working without a compiler or external resources, and debugging in your head- these are all major components of today’s tech interviews!

Taking It Personally

From there, computers got smaller and more powerful. Personal computers finally became a thing. Programming languages went from machine languages to more abstract languages. We got the internet, smart phones, social media, and all the good and bad that comes with the tech industry.

That pretty much brings us to today, where computer science is a huge, multidisciplinary industry.

Interviewing

I personally find this history interesting, but you might be wondering what it has to do with interviewing. What I’m trying to show is that today’s interview process didn’t spring up out of nowhere. There’s a whole history to how we’ve done tech interviews, which I think can help understand how they work today.

In the early days (the 40s, 50s, and 60s), computer science wasn’t really its own discipline. It was the stuff of complicated math and science, and the only people doing it were doctors, researchers, and engineers in highly specialized fields.

As time went on (the 70s and 80s), programming emerged as its own study. At this point, interviews were based more on experience than on whiteboard tests. Interviewers would read your resume and ask about projects you worked on. If you could talk about experience that was similar to the work you’d be doing at the company, you’d get the job. You might also be asked to write some example code on a piece of paper.

In the 1990s, as the internet became more popular, programming became more lucrative. More people were formally studying computer science in college and seeking jobs in the industry. The pen-and-paper interviews of the 80s gave way to whiteboard coding.

In the early 2000s, as Microsoft took over the world, it also took over the interviewing process. Microsoft became infamous for asking brain-teaser questions like “why are manhole covers round?” and Fermi estimation questions like “how many tennis balls can fit inside a school bus?” Other companies soon followed that trend.

Manhole cover in Roswell, New Mexico

That lasted for about ten years, until eventually everybody came to their senses about brain-teaser questions. In the early 2010s, Google’s head of people operations Laszlo Bock announced that Google would no longer ask brain-teaser questions at all.

Around this time, Google also switched from doing a ton of interviews for every candidate, to only doing 4 or 5. Sitting through 5 technical interviews is still stressful and a very long day, but it used to be even worse! Big tech companies also started using rubrics to assess candidates across the same set of categories instead of relying on stack-ranking and subjective yes/no decisions from individual interviewers.

Since then, most big tech companies have adopted the model of 4-5 technical whiteboard interviews, measured against a rubric. During Covid, most interview processes became fully virtual, where the whiteboard is now a shared text editor. But you still shouldn’t expect autocomplete or compiler errors!

The Interviewing Arms Race

As the interviewing process of big tech companies has evolved, an entire meta-industry has evolved alongside it, devoted to helping people get through it (or at least claiming to help people get through it).

Books like Cracking the Coding Interview have been written about the process. Sites like Leetcode and Glassdoor are devoted to collecting interview questions. There are even services where you can pay a ton of money for a mock interview. (Side note: don’t do this. Mock interviews with your friends are free and more valuable!)

Cracking the Coding Interview

This has caused a bit of an arms race, where external sites post a company’s questions, so the company bans those questions and comes up with new ones. Then the new question gets posted and banned, and the process repeats all over again. Paradoxically, these interviewing resources might have made the process harder as companies constantly try to stay ahead, and this is why the specifics of individual company processes are hard to pin down. However, the fundamentals have stayed relatively the same for the past 15 years or so.

I’ll talk more about these resources that try to capture interview questions in the next tutorial!

The Next Generation

This arms race, coupled with people generally becoming more vocal about the problems with traditional whiteboard interviewing, have caused a pushback against the current interviewing process. More companies are starting to lean more heavily on project-based interviews, rather than making candidates jump through algorithmic brain-teaser hoops.

Byteboard was founded (originally at Google) with the goal of improving the interview process. People have created lists on GitHub collecting companies that don’t do whiteboard interviews.

I honestly believe big tech will shift towards this model over the next ten years or so. But for now, the best I can do is help people through the process we have now.

More Info

For the sake of keeping this article short (okay, relatively short), I’ve oversimplified quite a bit. If you want to learn more about the history of computer science and tech interviewing, see these links for more info:

- Algorithm - Wikipedia is a great starting point, especially the History section.

- List of pioneers in computer science - Wikipedia is a who’s who of computer science. I recommend sorting by date and reading through to get a sense of how we got where we are today.

- List of computer term etymologies - Wikipedia is a glossary of how a bunch of computer terms got their names.

- History of computing hardware - Wikipedia

- History of computer science - Wikipedia

- History of computers: A brief timeline - Live Science

- What’s a Turing Machine? (And Why Does It Matter?)

- Turing’s Enduring Importance

- computer - Britannica is a surprisingly in-depth article on computers.

- Timeline of Computer History is an interactive timeline.

- Has anyone here been programming seriously since the 70s and 80s? What was it like? How has your experience of the field changed? is a Reddit post with fascinating replies.

- Computer programming in the punched card era - Wikipedia describes what coding was like in the 60s and 70s.

- Punch Card Programming - Computerphile - YouTube

- What were interviews for programming positions like in the 70s and 80s? - Hacker News

- What were interviews for programming positions like in the 70s and 80s? - Quora

- A History of Coding Interviews