Complexity

Complexity

- Runtime

- Other People Have Computers Too

- Time Complexity

- Big O Notation

- Why Constants Don’t Matter

- Beyond Linear Time

- Quadratic Time

- Worst Case Scenario

- Multiplier Improvements

- Order Improvements

- Real Life Improvements

- Common Complexities

- Space Complexity

Algorithmic analysis. Time and space complexity. Big-O notation. These terms come up often in interviewing, and they generally bring with them a sense of fear and uncertainty, if not outright dread. 😱

Although these concepts have roots in theoretical computer science, they’re motivated by practical concerns that you’ve probably run into already.

This tutorial starts with those practical concerns, and uses plenty of examples to explain algorithmic complexity and Big O notation.

Runtime

Let’s say you have an array of int values, and you want to return their total.

static int getTotal(int[] array) {

int total = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

total += array[i];

}

return total;

}

How long will this function take to run?

Before you answer that, think about why this question might be important. Computers run pretty fast, but not instantly. Slow code results in slower applications and frustrated users. Slow code can even mean the difference between solving or not solving a problem. So the question of “how fast is this code?” is still important, even today.

Okay, back to the question: how long will the getTotal() function take to run?

To answer that, you might write some code that times it:

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] array = new int[10];

long start = System.nanoTime();

int total = getTotal(array);

long end = System.nanoTime();

long elapsed = end - start;

System.out.println(elapsed);

}

This code uses the System.nanoTime() function to time how long it takes to run the getTotal() function with an array of size 10, and then prints the elapsed time out.

If I run this on my computer, I can see that the getTotal() function takes about 1000 nanoseconds to run. That’s 0.0001% of a second, which seems pretty fast!

But wait, the getTotal() function takes an array as a parameter. The code above times the getTotal() function when that array contains 10 elements. What happens if you pass in a larger array?

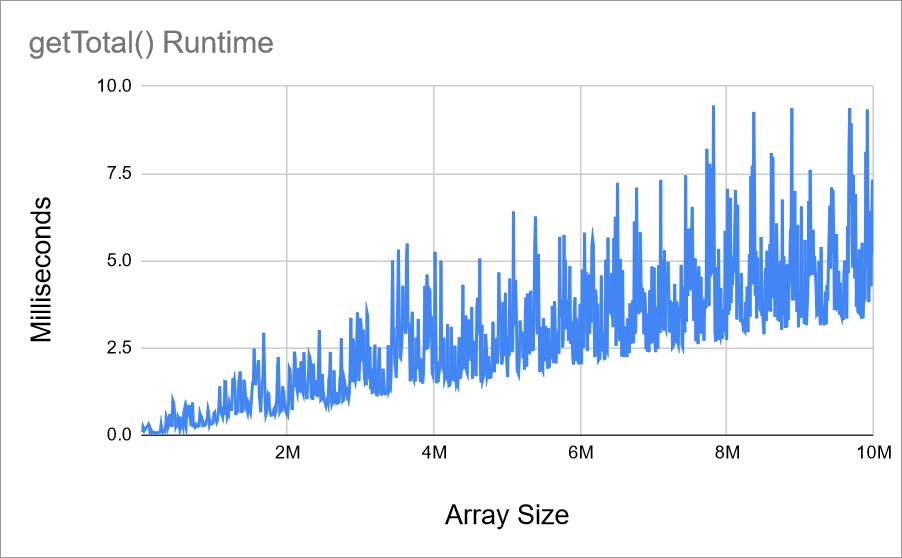

You can test that manually by increasing the size of the array: change the 10 to a 100 or even a 10000000 and you’ll see the elapsed time change along with it. You could even get fancy and chart out a graph of the time it takes for different inputs:

public class ComplexityPrinter {

public static void main(String[] args) {

for (int size = 10_000; size <= 10_000_000; size += 10_000) {

long elapsed = measureOneRun(size);

System.out.println(size + ", " + elapsed);

}

}

static long measureOneRun(int size) {

int[] array = new int[size];

long start = System.nanoTime();

int total = getTotal(array);

long end = System.nanoTime();

long elapsed = end - start;

return elapsed;

}

static int getTotal(int[] array) {

int total = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

total += array[i];

}

return total;

}

}

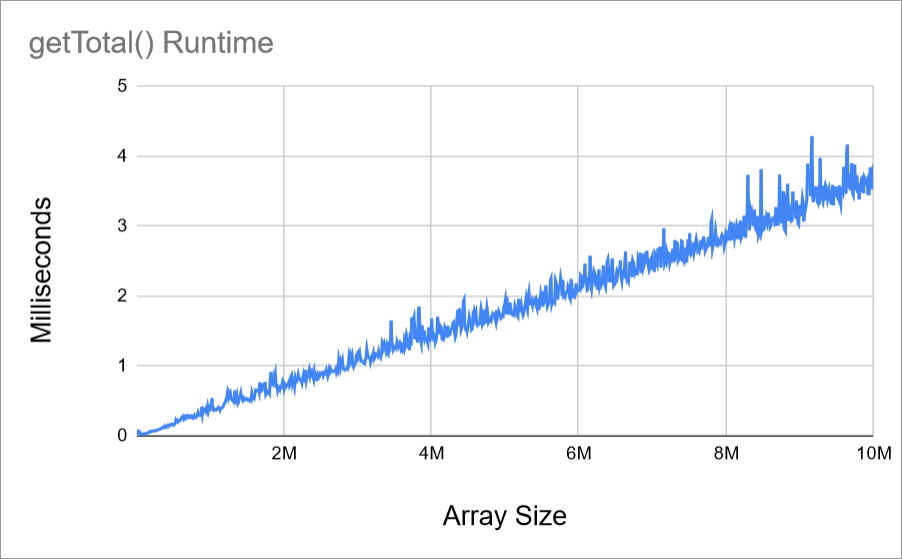

This code prints out a list of array sizes, and how long the getTotal() function takes for each size. You can then put it in a chart to visualize it:

This chart is a reasonable visualization, but it’s pretty noisy. It contains spikes caused by my computer being busy doing other stuff while it’s running the getTotal() function. System updates, my own browsing, or plain old luck can cause my computer to run faster or slower at different times, so measuring a single function call isn’t very accurate.

You can fix this by running the function multiple times, and then taking the average:

public class ComplexityPrinter {

public static void main(String[] args) {

for(int size = 10_000; size <= 10_000_000; size += 10_000){

long elapsed = measureAverageRuns(size);

System.out.println(size + ", " + elapsed);

}

}

static long measureAverageRuns(int size){

int runs = 10;

long totalElapsed = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < runs; i++){

totalElapsed += measureOneRun(size);

}

return totalElapsed / runs;

}

static long measureOneRun(int size){

int[] array = new int[size];

long start = System.nanoTime();

int total = getTotal(array);

long end = System.nanoTime();

long elapsed = end - start;

return elapsed;

}

static int getTotal(int[] array) {

int total = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < array.length; i++){

total += array[i];

}

return total;

}

}

The chart is still a little noisy because I only ran each size 10 times. You can make your chart more smooth by increasing the number of runs to average, but you’ll end up waiting longer for your results.

Anyway, now you can answer the question “how long does this function take to run?” by pointing at your chart. All done, right?

Oh wait…

Other People Have Computers Too

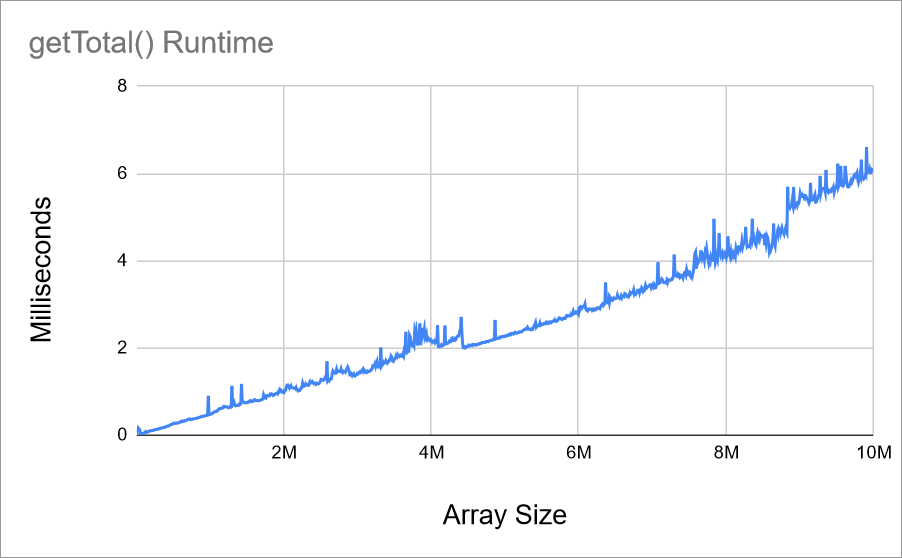

The above charts show the getTotal() function’s runtime on my computer. But if I run the same program on a different computer, the runtime looks a little different:

This other computer is a little slower, so the function takes a little longer when I run it there. And if you ran the code on your computer, your chart probably looked a little different too.

So, measuring the pure time that the function takes isn’t very helpful, because it depends on factors you can’t control, and often can’t know ahead of time.

Time Complexity

Instead of measuring the pure time that a function takes, you can think in terms of how many individual actions your function or algorithm executes.

Consider this code:

static void printWords() {

System.out.println("Hello");

System.out.println("World");

System.out.println("!");

}

Let’s say this code executes three individual actions: it calls System.out.println() three times. In reality it’s probably more than that, because each call to System.out.println() executes multiple actions internally. But you’ll see in a second that it doesn’t really matter, so saying this is three actions for now is fine.

How about this code?

static void printNumbers() {

System.out.println("Printing numbers...");

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

System.out.println(i);

}

System.out.println("Done printing numbers.");

}

This code prints "Printing numbers..." which we’ve said counts as a single action. Then it creates a for loop, which we’re also going to say counts as a single action. Then it loops 10 times, and during each iteration of the loop it prints a number. Finally, the code prints one more message and then exits.

So the number of individual steps is something like this:

1

+ 1

+ 10 * 1

+ 1

= 13 individual actions

Now how about this code?

static int getTotal(int[] array) {

int total = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

total += array[i];

}

return total;

}

Similar to measuring how much time this function took, the answer is that it depends on the size of the array. Imagine array.length is now a variable named n. And let’s say that total += array[i]; counts as two individual steps: one to read from array, and one to increment the total variable. The number of individual steps would be something like this:

1

+ 1

+ n * 2

+ 1

= 3 + n * 2 individual actions

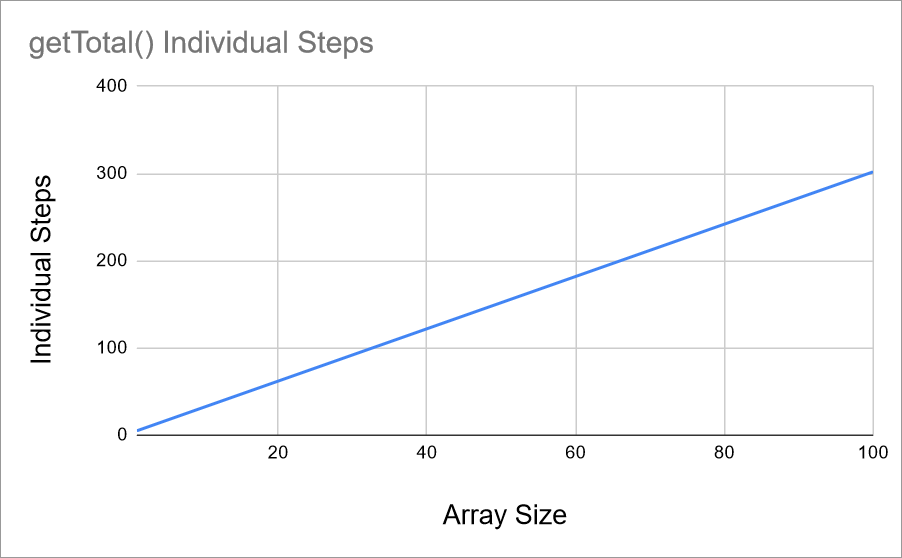

You can graph this out, very similar to the time measurements:

This chart is a more accurate measurement of the function, because it doesn’t change based on which computer it’s running on, or what else the computer is doing at the time.

Big O Notation

Now you have an equation that calculates the number of individual steps the getTotal() function executes: 3 + n * 2.

In theory, you could calculate the total number of steps for every function you write. But maintaining these calculations is next to impossible: we’ve already oversimplified by saying that System.out.println() counts as a single step, when in reality it’s probably executing many actions every time it’s called.

You could go a level deeper and calculate how many steps System.out.println() really executes, and you could do the same for any other function you call. That would be tedious, but theoretically doable. But what happens if you update to a new version of Java? You’d have to recalculate all of that, for every function you call, in every function you’ve ever written.

Big O notation is a way to cut through all of that, while still preserving the main goals of being able to talk about how long an algorithm will take to run. Big O might feel complicated, but its goal is to simplify these equations when you’re talking about them and comparing them.

To go from an equation like 3 + n * 2 to Big O notation, do the following:

- Eliminate any constants, in this case the

3 - Eliminate any multipliers, in this case the

2 - Keep the

nwith the largest exponent, eliminate the rest - If nothing remains, your algorithm runs in constant time, meaning it doesn’t depend on the size of any inputs. This is as fast as you can get.

- If an

nremains, your algorithm is “oh of” thatn, e.g.O(n)(oh of n),O(n^2)(oh of n squared), etc

If you apply that process to 3 + n * 2, you get a single n, so you’d say that the getTotal() function has a time complexity O(n), or “oh of n”. This is also called linear complexity, because the complexity grows linearly. Which makes sense if you look at the chart!

Why Constants Don’t Matter

Functions that always execute the same number of individual steps every time they’re called, regardless of what parameters you give them, are said to run in constant time. In other words, even if you increase the size of the parameter, the individual steps remain constant.

Earlier I said that it didn’t really matter how many individual steps the System.out.println() function took internally, and the Big O process is why.

For example, consider this code:

static void printNumbers(int n) {

System.out.println("Printing numbers...");

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

System.out.println(i);

}

System.out.println("Done printing numbers.");

}

If System.out.println() took 10 steps internally, the calculation of the total individual steps for the printNumbers() function would be:

10

+ 1

+ n * 10

+ 10

= 21 + n * 10

And after dropping the constants, the Big O for that would be O(n).

Now if System.out.println() took 100 steps internally, the calculation of the total individual steps for the printNumbers() function would be:

100

+ 1

+ n * 100

+ 100

= 201 + n * 100

And after dropping the constants, the Big O for that would be… O(n) again!

So in terms of Big O, the exact numbers for the constants don’t really matter. In fact, when calculating Big O, you often skip over statements that run in constant time, or group them all together into a hand-wavey “and here I do some constant time stuff” box.

Algorithms or functions that run in constant time have a Big O notation of O(1). Even if the algorithm executes 1,000,000 individual actions, the Big O is still O(1), which means “no matter how big n gets, the runtime stays the same”.

It might seem like you’re throwing away a lot of data when you drop constants from Big O notation, but that’s okay! The goal of Big O notation is to make it easier talk about how long an algorithm will take in broad terms, not in very specific equations.

Beyond Linear Time

The above examples show code that either runs in constant time / O(1) (code with a runtime that doesn’t change based on input) or linear time / O(n) (code that takes longer to run with longer input). That might seem like the only two options- runtime either increases based on the size of the input or it doesn’t, right?

But after you know that code takes longer to run with longer input, the next question becomes how much more time does it take? In other words: as the size of the input increases, how much does the runtime increase?

Consider this code:

static boolean containsDuplicates(int[] input) {

for (int i = 0; i < input.length; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < input.length; j++) {

if (i == j) {

// Don't compare elements with themselves

continue;

}

if (input[i] == input[j]) {

return true;

}

}

}

return false;

}

This code takes in an array, and then uses a for loop to iterate over every element in the array. It then uses another for loop to iterate over every other element. If the two elements are equal but they aren’t the same index, the function returns true. If the code exits both for loops, the function returns false. In other words, this function returns whether the array contains at least one duplicate.

How long does this function take to run?

To answer that, you could build a similar program that measures it:

public class ComplexityPrinter {

public static void main(String[] args) {

for(int size = 10_000; size <= 10_000_000; size += 10_000) {

long elapsed = measureAverageRuns(size);

System.out.println(size + ", " + elapsed);

}

}

private static long measureAverageRuns(int size){

long total = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < 10; i++){

total += measureOneRun(size);

}

return total / 10;

}

private static long measureOneRun(int size){

int[] input = getArray(size);

long startTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

boolean containsDuplicates = containsDuplicates(input);

long endTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

long elapsed = endTime - startTime;

return elapsed;

}

public static boolean containsDuplicates(int[] input) {

for(int i = 0; i < input.length; i++){

for(int j = 0; j < input.length; j++) {

if(i == j) {

// don't compare elements with themselves

continue;

}

if(input[i] == input[j]){

return true;

}

}

}

return false;

}

public static int[] getArray(int size) {

int[] array = new int[size];

// Fill the array with 0, 1, 2... up to size

for(int i = 0; i < size; i++){;

array[i] = i;

}

// Make the last two elements the same number

// so the algorithm has to search the entire array to find duplicates

array[size - 1] = -1;

array[size - 2] = -1;

return array;

}

}

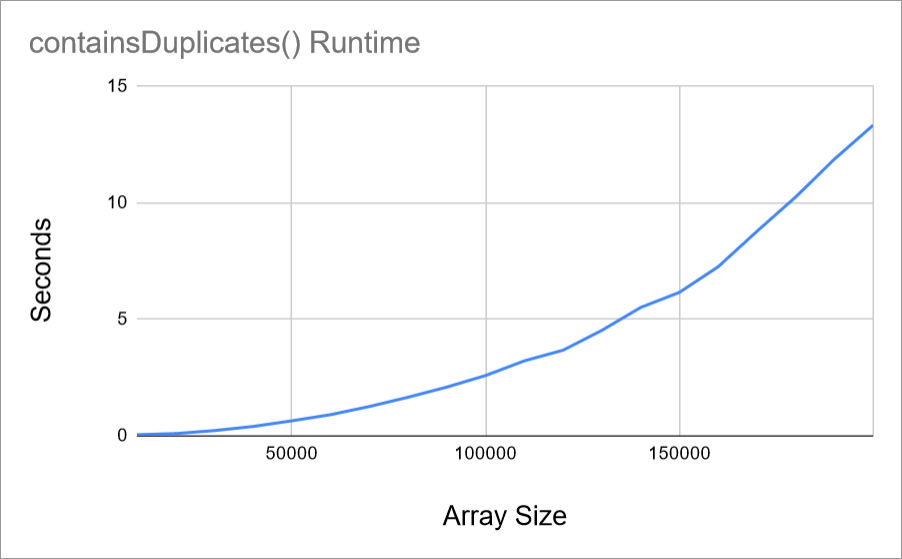

And if you graph the output, it looks like this:

The exact numbers don’t matter, but the important thing to notice is that this graph isn’t a straight line!

In the earlier example, the getTotal() function scaled in a straight line. As the size of the array increased, the runtime increased at the same rate. But now, the runtime of the containsDuplicates() function increases more as the size of the array increases.

In other words, if you add 10 elements to the array, the runtime will go up by some amount. But if you add 10 more elements, the runtime will go up by more than it did for the first 10 elements! Even though the input size difference is the same, the runtime difference is bigger.

Quadratic Time

To understand why the runtime increases more as the array increases in size, think about these two lines of code:

for (int i = 0; i < input.length; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < input.length; j++) {

This code iterates over every element in the array. Then for each of those iterations, it iterates over every element in the array again. That means the total number of iterations for the entire nested for loop is input.length * input.length, or input.length ^ 2.

If input.length is 1, then you only get 1 iteration, because 1 * 1 = 1. But if input.length is 2, you get 4 iterations, because 2 * 2 = 4.

Here it is in table form:

| input.length | iterations |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 9 |

| 4 | 16 |

| … | … |

| 10 | 100 |

| 20 | 400 |

| 30 | 900 |

This means that adding a single element to the input doesn’t increase the total iterations by 1, it increases the iterations by how many elements are already in the array! As the array gets bigger, adding another element gets worse and worse.

This is called quadratic time, because the runtime graph increases quadratically instead of linearly. Specifically, this function has a Big O notation of O(n ^ 2) or oh of n squared.

Each level of nested iteration over the input increases the exponent by one. So a triply nested for loop would be O(n ^ 3), a quadruply nested for loop would be O(n ^ 4), etc.

Worst Case Scenario

The above containsDuplicates() function starts at the beginning of the array and looks for two elements that have the same value. But what happens if the array contains two duplicates right at the beginning of the array?

int[] array = {1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ...99999};

In this case, it doesn’t matter how many elements are in the array, because the function would find the duplicate and return almost immediately.

When analyzing an algorithm for its runtime complexity, you’re generally talking about the worst possible case. Assume the input is in the configuration that would cause the highest number of steps, and base your calculations on that.

Fun fact: similar to how Big O measures the worst possible runtime for an algorithm, Big Ω (Big Theta) measures the best possible runtime. This probably won’t come up in an interview, but learning about Big Theta helped me understand Big O.

Multiplier Improvements

The above containsDuplicates() function iterates over every element in the array, and then for each element, it iterates over the array again to find a duplicate. There’s a flaw in this logic!

Think about how you’d do this manually. If I gave you a pile of index cards with numbers written on them, how would you figure out whether the pile contained any duplicates? You might start by looking at the first card, and then looking in the rest of the pile for a matching card. If you didn’t find a duplicate, you might then take a second card out of the pile and repeat the process. But you wouldn’t compare the second card with the first card, because you know nothing matched the first card already!

In other words, for each element that the outer loop iterates over, the inner loop can skip over the elements that came before it.

Putting it into code:

public static boolean containsDuplicatesBetter(int[] input) {

// Loop until the second-to-last element

for (int i = 0; i < input.length - 1; i++) {

// Start at i + 1 to skip elements that have already been checked

for (int j = i + 1; j < input.length; j++) {

if (input[i] == input[j]) {

return true;

}

}

}

return false;

}

What’s the runtime complexity of this function?

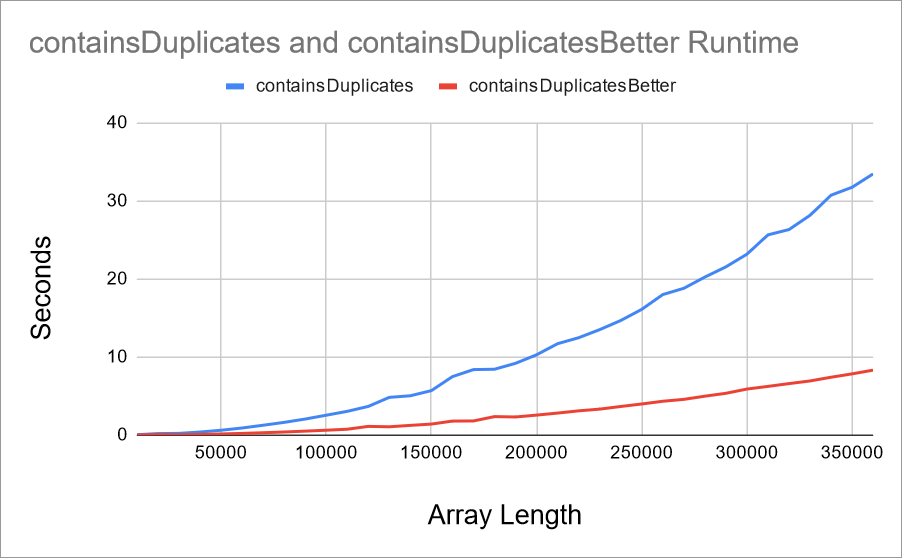

Well, you could time it and graph it out:

That looks like an improvement! But how many individual actions does the code execute?

To figure that out, think about how many iterations the inner loop executes for an array of size 5:

- When

iis0, the inner loop iterates4times (indexes 1, 2, 3, and 4) - When

iis1, the inner loop iterates3times (indexes 2, 3, and 4) - When

iis2, the inner loop iterates2times (indexes 3 and 4) - When

iis3, the inner loop iterates1times (index 1)

So for an array of size 5, the code iterates 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 10 times.

If you want to calculate the total iterations for an arbitrary length n, thanks to some fancy math you can use the formula (n ^ 2 + n ) / 2.

And to go from a formula to Big O notation, you follow these steps:

- Eliminate any constants, in this case that’s already done

- Eliminate any multipliers, in this case the

/ 2 - Keep the

nwith the largest exponent, in this case keep then ^ 2 - If an

nremains, your algorithm is “oh of” thatn

Which means even though the actual measured time has improved, the Big O has not changed! The containsDuplicatesBetter() function is still O(n ^ 2).

Order Improvements

It might seem counterintuitive that the containsDuplicates() and containsDuplicatesBetter() functions have the same Big O of O(n ^ 2), even though the containsDuplicatesBetter() function is about twice as fast.

But think about what it means to be twice as fast. If you have an algorithm that takes 10 minutes to process your data, taking that down to 5 minutes isn’t that big a difference.

But if you can take that algorithm from 10 minutes down to 1 second? That’s a huge difference. And expressing those kinds of differences is what Big O is all about.

For example, this function uses a HashSet to check for duplicates:

public static boolean containsDuplicatesLinear(int[] input) {

Set<Integer> seenSoFar = new HashSet<>();

for (int i = 0; i < input.length; i++) {

if (seenSoFar.contains(input[i])) {

return true;

}

seenSoFar.add(input[i]);

}

return false;

}

What’s the runtime complexity of this function?

To answer that, think about how many individual steps this code executes.

- First, the code creates a

HashSet, which is constant time. You can consider this a single individual step, or you can ignore it since you know you’ll drop the constants at the end anyway. - Then, the code iterates over the entire input, which is linear time. Anything inside that for loop will be multiplied by

n.- The

HashSet#contains()function runs in constant time. So doesreturn true, and so does theHashSet#add()function! That means everything in the loop is constant!

- The

- Finally,

return false;is also constant.

Putting that all together, you get something like this:

1

+ n * 3

+ 1

= 2 + n * 3

The Big O notation for this equation is O(n), meaning this whole function runs in linear time!

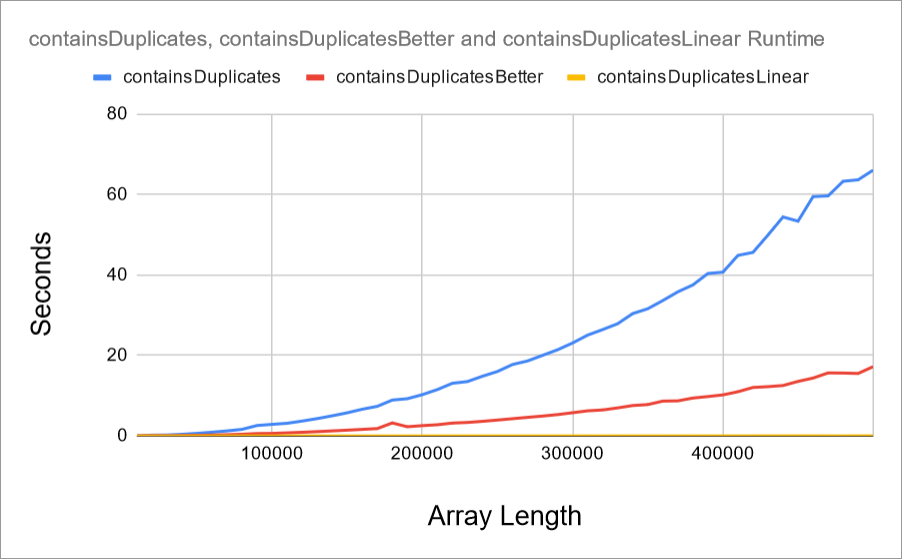

Measuring it and graphing it out shows why this is such a big deal:

The original containsDuplicates() function looks pretty bad by comparison. But now even the containsDuplicatesBetter() function doesn’t look great either, because the containsDuplicatesLinear() function is so small by comparison that it’s barely visible on this chart.

That’s why Big O notation throws away so much information, and doesn’t seem to care about improvements that “only” multiply the speed by a constant factor. Even if one O(n ^ 2) algorithm is 100 times faster than another O(n ^ 2) function, it’s still not going to beat an O(n) algorithm. And an O(n) algorithm isn’t going to beat an O(1) algorithm.

Real Life Improvements

Big O might not care about improvements that change an algorithm’s runtime by a constant factor, but those improvements still matter in real life!

If you can find ways to improve your algorithm by a constant factor, you should absolutely include those improvements in your code. For example, containsDuplicatesBetter() avoided making a ton of unnecessary comparisons. And although that didn’t change the Big O notation, making that improvement shows that you’re thinking about efficiency.

Common Complexities

Hopefully now you have a sense of what Big O attempts to convey. You also know how to calculate it, by thinking about how many individual steps it takes, and then reducing that equation to the Big O notation.

You’ve seen Big O notations of O(1), O(n), and O(n ^ 2), but there are many others. Here are a few common ones:

O(1)is constant time. Note that even if an algorithm takes 100 individual steps, it still has a Big O ofO(1). Examples include printing a single value, executing an if statement, or looping 1000 times.O(log n)is logarithmic time. This is popular in algorithms that repeatedly cut the input in half, like doing a binary search in a sorted array, or navigating through a balanced binary tree.O(n)is linear time. Examples include iterating over an array, or doing something with every character in a string, or with every binary bit in a number.O(n log n)is loglinear time. The main example of this is sorting an array with mergesort, which is handy to know because many algorithms rely on having sorted data. If you need to sort your data first, you’re probably starting with a minimum ofO(n log n)time.O(n ^ 2)is quadratic time. Examples include brute force solutions that use a nested for loop to iterate over every possible pair within an input.O(n ^ c)wherecis some other number is polynomial time. For example, if you have a triple-nested for loop where each level iterates over the entire array, that’sO(n ^ 3)time.O(n!)is factorial time. Examples of this are generating every rearrangement or permutation of an input.

Many interview questions have a brute force solution that runs in polynomial time, and one or more “optimal” solutions that run in linear time.

Space Complexity

So far, I’ve talked about runtime complexity, as well as using Big O notation to talk about and compare how much time different algorithms will take.

Runtime complexity is important in algorithm development and interviews, but it’s not the only consideration. You should also consider how much space (in other words, how much memory) your algorithm requires!

For example, the containsDuplicatesLinear() function created an extra HashSet as part of its algorithm. For an array of size n, it creates a HashSet of size n, which means it has a space complexity of O(n).

Algorithms are often a tradeoff between runtime complexity and space complexity. Using a data structure that requires O(n) space is generally worth it, especially because any function that takes an input already has a space complexity of O(n). But watch out for algorithms that require massive data structures.

Most importantly, keep in mind that an interview is a conversation between you and the interviewer. There often isn’t one “right” answer to a question. It’s a series of tradeoffs, and your goal should be to talk through those tradeoffs. Rather than seeing Big O as an intimidating academic exercise, see it as a way to talk about these tradeoffs.