Swing

Swing

- A Brief History

- JFrame

- Components

- JTextArea

- JPanel

- Layout Managers

- Nesting Layouts

- Event Listeners

- Custom Painting

- Timers

- Other Resources

- Homework

So far, all of our Java programs have been command line programs, which we interacted with through the command prompt, if we interacted with the program at all.

Command line programs are fine for simple tasks or for programs that don’t really interact with the user, but if you want to interact with the user, then you probably want to create a graphical user interface, or GUI (pronounced “gee-you-eye” or “gooey”). GUIs are the types of programs you’re probably more accustomed to using: the types of programs that have windows and buttons and text fields instead of only using the command prompt.

Java contains a bunch of classes that help you create GUIs, and this tutorial focuses on a set of classes that make up a library called Swing.

Note: Swing is not an acronym! (Neither is Java, for that matter.)

A Brief History

Java contains three different GUI libraries, which are each just a bunch of classes in the Java API that you can use. Trying to understand how all of these classes fit together can be confusing, so here’s a brief summary of how they work:

-

The Abstract Window Toolkit, or AWT, has been a part of Java since day one, way back in 1996. AWT works by passing in “native” calls to your computer. So if you create a checkbox in AWT, you’re really telling your operating system to create a checkbox. All of the AWT classes are in the

java.awtpackage. -

The downside of that approach is that your program will look different on different computers: a checkbox on Linux looks different from a checkbox on Windows. This can make it harder to layout your program or have a consistent experience across different platforms. To fix this, Swing was added to Java in 1998. The idea behind Swing is that instead of telling your computer to create a checkbox, Swing draws the checkbox itself. That way, the checkbox will look the same on different operating systems. The Swing classes are in the

javax.swingpackage. But Swing was built on top of AWT, so you’ll see Swing code using classes from thejava.awtpackage as well. -

JavaFX was originally developed as an external library in 2008, and it was included in Java in 2014. JavaFX focuses on modern GUI features, like more animations, CSS styling, and using a computer’s graphics card to handle the rendering. JavaFX classes are in the

javafxpackage, which is in a.jarfile that comes with Java.

Even though JavaFX is newer, I’m focusing on Swing for a couple reasons:

-

The benefit of Swing being around longer is that there are a ton of resources for learning more about it. If you’re wondering how to do something in Swing, chances are somebody has asked your question on Stack Overflow.

-

I think Swing is a great way to become more comfortable with OOP, inheritance, and general program flow. So even if your end goal with programming isn’t Swing, it’s a good idea to spend some time here because it’ll help you learn other stuff you need to be learning.

-

I know Swing better than I know JavaFX.

One more thing worth noting: the above libraries, including Swing, are for creating a desktop application, which is a program that runs on your computer, not in a webpage. Think of opening up the Spotify application, not going to Spotify’s website. But like I said above, even if your end goal isn’t creating a desktop application in Java, it’s still a good idea to learn this stuff since it teaches you other stuff you need to know anyway.

Enough history, to the tutorial!

JFrame

The first step to creating a GUI is displaying a window, so you can interact with that instead of the command prompt. The JFrame class is Swing’s representation of a window, and it works like this:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

Let’s take it one line of code at a time:

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

This line of code creates an instance of the JFrame class, passing in a parameter that sets the title of the window.

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

This makes it so when you click the X button in the window, your program exits. If you don’t do this, your program could continue running in the background even after the window closes, which you probably don’t want.

frame.setSize(300, 300);

This line of code sets the width and height of the window in pixels. Try passing in different values to change the size of the window.

frame.setVisible(true);

Finally, this actually pops the window up and shows it to the user. Notice that the program continues running even after our main() function ends!

Usually you wouldn’t put all of your code in the main() method like that, except for very simple programs like this one. You would probably do something like this:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

public class MyGui{

public MyGui(){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

public static void main(String[] args){

new MyGui();

}

}

This code moves the logic from the main() function into the class, and the main() function simply creates an instance of that class. This isn’t much different from putting it all in the main() method, but this will make more sense as your code gets more complicated.

You might also split your code up like this:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

public class MyGui{

private JFrame frame;

public MyGui(){

frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

}

public void show(){

frame.setVisible(true);

}

public static void main(String[] args){

MyGui myGui = new MyGui();

myGui.show();

}

}

This code does the same thing, but it splits the code up: it initializes the frame variable in the constructor, and it shows it in the show() function.

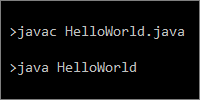

In any case, you would save this to a file named MyGui.java and then you’d compile and run it from the command line, just like the other programs we’ve seen so far. (Yeah, you still have to compile and run using the command line. We’ll talk about how to create an executable file in a later tutorial!)

The code causes a window to show:

Our window is blank, because we haven’t added anything to it yet.

Components

In addition to the JFrame class, Swing has a bunch of classes that represent different components you can add to a window: stuff like buttons, labels, checkboxes, and text areas. To use a component, you call frame.add(component); to add it to the window. We’ll see some examples below.

As always, your best friend is the Java API, but here are a few of the most commonly used classes:

JButton

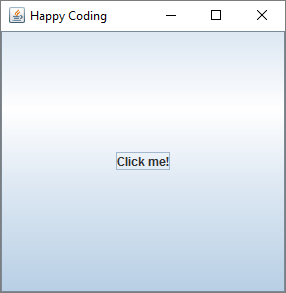

The JButton class is Swing’s representation of a clickable button. Let’s add it to our GUI:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JButton;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JButton button = new JButton("Click me!");

frame.add(button);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

First we construct a JFrame and make it so the program ends when we close it. Then we create an instance of the JButton class, passing in an argument that sets the text of the button. Then we add the button the the window. Finally, we set the size of the window and show it.

Right now the button just takes up the whole window, and nothing happens when you click it. We’ll fix that in a second.

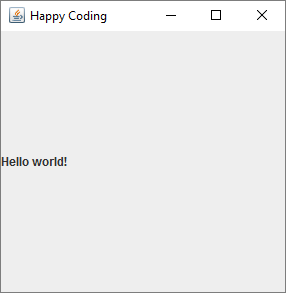

JLabel

The JLabel class is Swing’s representation of an undeditable text label. Let’s add it to our GUI:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JLabel;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JLabel label = new JLabel("Hello world!");

frame.add(label);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

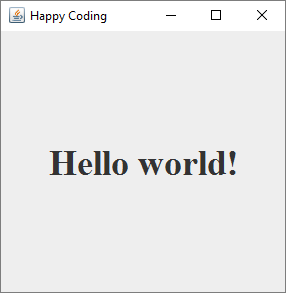

This is almost the same as the JButton code, except now we’re creating an instance of JLabel and adding it to the JFrame.

Right now the label is left-aligned and uses the default font. We can fix that by calling functions on our JLabel instance:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JLabel;

import java.awt.Font;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JLabel label = new JLabel("Hello world!");

label.setFont(new Font("Serif", Font.BOLD, 36));

label.setHorizontalAlignment(JLabel.CENTER);

frame.add(label);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

Now our JLabel has a large bold serif font, which it displays using a center alignment.

You can find other ways to customize your components by looking them up in the Java API! Try changing the text color of the JLabel.

JTextArea

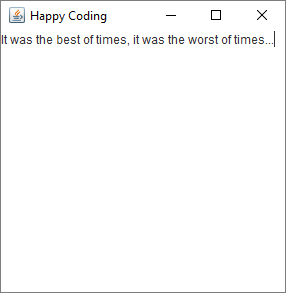

The JTextArea class is Swing’s representation of a box of text that the user can edit.

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JTextArea;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JTextArea textArea = new JTextArea("It was the best of times, it was the worst of times...");

frame.add(textArea);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

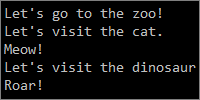

This gives us a box of text that the user can type into:

Again, you can customize this component using functions you find in the Java API. Try changing the font!

Other Components

This tutorial isn’t meant to show you every single thing you can do with Swing. It’s meant to show you the basics so you can use the Java API to figure out exactly how to do what you want. Here are just a few other components you should check out:

-

JCheckBoxandJRadioButtonrepresent checkboxes and radio buttons. -

JTextFieldgives you a one-line text area. -

JComboBoxandJListallow the user to select items from lists. -

JMenulets you add menus to your window. -

JProgressBarshows a progress bar. -

JSliderandJSpinnerlet the user adjust a value. -

JTableshows a table of data. -

JScrollPaneadds scroll bars to content that’s too large to fit in the window.

To learn how to use these components, look them up in the Java API and read about the constructors, functions, and variables they contain. Then put together a little example program that tests the component out before integrating it into your main project.

JPanel

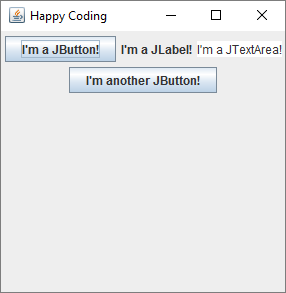

So far, we’ve only added a single component to our window. That’s not very exciting, but we can use the JPanel class to add multiple components to a window. JPanel is a component that holds other components. To use a JPanel, you’d follow this basic flow:

- Create an instance of

JPanel. - Add components to the

JPanelinstance. - Add that

JPanelto theJFrame.

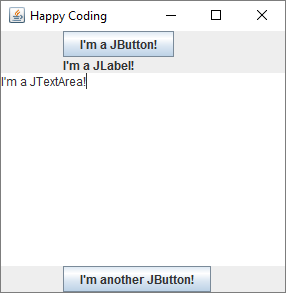

It looks like this:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.JButton;

import javax.swing.JLabel;

import javax.swing.JTextArea;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JPanel panel = new JPanel();

JButton buttonOne = new JButton("I'm a JButton!");

panel.add(buttonOne);

JLabel label = new JLabel("I'm a JLabel!");

panel.add(label);

JTextArea textArea = new JTextArea("I'm a JTextArea!");

panel.add(textArea);

JButton buttonTwo = new JButton("I'm another JButton!");

panel.add(buttonTwo);

frame.add(panel);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

This code creates a JFrame, then creates a JPanel instance. It adds four different components to the JPanel, and then it adds that JPanel to the JFrame. Finally, it sets the size of the JFrame and shows it.

By default, the components are displayed one after the other, and they wrap to multiple rows if the window is not wide enough to fit them. Try changing the width of the window to see the components rearrange themselves.

Layout Managers

You probably don’t want your components to be display like that though. You can change how they’re arranged using layout managers, which are classes that tell a JPanel how to arrange components.

To use a layout manager, you first create an instance of the layout manager you want to use, and then you pass it into the setLayout() function of your JPanel. It looks like this:

JPanel panel = new JPanel();

BorderLayout borderLayoutManager = new BorderLayout();

panel.setLayout(borderLayoutManager);

Of course, you can also pass the instance directly into the function instead of storing it in a variable first:

JPanel panel = new JPanel();

panel.setLayout(new BorderLayout());

And the JPanel constructor can take a layout manager as an argument:

JPanel panel = new JPanel(new BorderLayout());

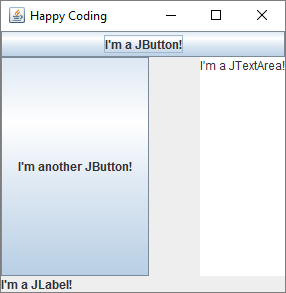

In any case, this code uses a BorderLayout layout manager, which splits the JPanel up into 5 different areas: the top of the JPanel is NORTH, the bottom is SOUTH, the left is WEST, the right is EAST, and the center is, well, CENTER. You can pass these values (which are static variables in the BorderLayout class) into the add() function along with the component to arrange them. Putting it all together, it looks like this:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.JButton;

import javax.swing.JLabel;

import javax.swing.JTextArea;

import java.awt.BorderLayout;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JPanel panel = new JPanel();

BorderLayout borderLayoutManager = new BorderLayout();

panel.setLayout(borderLayoutManager);

JButton buttonOne = new JButton("I'm a JButton!");

panel.add(buttonOne, BorderLayout.NORTH);

JLabel label = new JLabel("I'm a JLabel!");

panel.add(label, BorderLayout.SOUTH);

JTextArea textArea = new JTextArea("I'm a JTextArea!");

panel.add(textArea, BorderLayout.EAST);

JButton buttonTwo = new JButton("I'm another JButton!");

panel.add(buttonTwo, BorderLayout.WEST);

frame.add(panel);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

This code uses a BorderLayout layout manager, and adds each component to a different section of the JPanel.

Notice that the components stay in their positions, even when you resize the window. Also notice that the size of each component is set by the layout.

There are a bunch of other layout managers, and this tutorial is a great place to learn more about them. Here’s an example that uses BoxLayout:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.JButton;

import javax.swing.JLabel;

import javax.swing.JTextArea;

import javax.swing.BoxLayout;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JPanel panel = new JPanel();

BoxLayout boxLayoutManager = new BoxLayout(panel, BoxLayout.Y_AXIS);

panel.setLayout(boxLayoutManager);

JButton buttonOne = new JButton("I'm a JButton!");

panel.add(buttonOne);

JLabel label = new JLabel("I'm a JLabel!");

panel.add(label);

JTextArea textArea = new JTextArea("I'm a JTextArea!");

panel.add(textArea);

JButton buttonTwo = new JButton("I'm another JButton!");

panel.add(buttonTwo);

frame.add(panel);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

This code sets a BoxLayout layout manager, which arranges the components in a single line, either horizontally or vertically depending on the value you pass into the BoxLayout constructor. Try changing the parameter to BoxLayout.X_AXIS to see what happens!

Again, notice that the size of the components depends on the layout you use! This can be a little confusing, but it helps make sure your components do reasonable things when the user resizes the window.

Nesting Layouts

Remember that we can add components to JPanel instances, and JPanel is itself a component. That means we can add components to a JPanel with one layout manager, and then add that JPanel to another JPanel with a different layout manager! This is called nesting layouts, and it lets us bundle up multiple components and treat them as a single block in the overall layout.

If that sounds confusing, think about it this way: we can create a JPanel with a vertical BoxLayout that contains 5 JButton instances. Then we can create another JPanel with a BorderLayout layout manager, and we can add the first JPanel to the WEST section of the second JPanel!

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.JButton;

import javax.swing.JLabel;

import javax.swing.BoxLayout;

import java.awt.BorderLayout;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JPanel leftPanel = new JPanel();

BoxLayout leftBoxLayoutManager = new BoxLayout(leftPanel, BoxLayout.Y_AXIS);

leftPanel.setLayout(leftBoxLayoutManager);

leftPanel.add(new JButton("JButton One"));

leftPanel.add(new JButton("JButton Two"));

leftPanel.add(new JButton("JButton Three"));

leftPanel.add(new JButton("JButton Four"));

leftPanel.add(new JButton("JButton Five"));

JPanel rightPanel = new JPanel();

BoxLayout rightBoxLayoutManager = new BoxLayout(rightPanel, BoxLayout.Y_AXIS);

rightPanel.setLayout(rightBoxLayoutManager);

rightPanel.add(new JLabel("JLabel One"));

rightPanel.add(new JLabel("JLabel Two"));

rightPanel.add(new JLabel("JLabel Three"));

rightPanel.add(new JLabel("JLabel Four"));

rightPanel.add(new JLabel("JLabel Five"));

JPanel mainPanel = new JPanel(new BorderLayout());

mainPanel.add(leftPanel, BorderLayout.WEST);

mainPanel.add(rightPanel, BorderLayout.EAST);

frame.add(mainPanel);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

This code creates a JPanel with a vertical BoxLayout, then adds five JButton components to it. Then it creates another JPanel with another vertical BoxLayout, and it adds five JLabel components to it. Then it creates a third JPanel with a BorderLayout layout manager, and it adds the first two JPanel components to it.

In other words, it treats each set of components as a block that it lays out in the main window layout.

There isn’t really a limit to how much nesting you can have!

Event Listeners

So far, our components haven’t done anything other than display. Nothing happens when we click a button, for example. We can change that by adding event listeners to our components.

Event listeners are objects that define functions that are called when a certain event happens: when the user clicks the mouse or presses a key on the keyboard, for example.

For example, let’s create an ActionListener, which lets us trigger a function when the user clicks a button. ActionListener is an interface, so the first step is to create a class that implements that interface:

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

public class SimpleActionListener implements ActionListener{

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event){

System.out.println("Clicked!");

}

}

The ActionListener interface requires a single function named actionPerformed(), and our SimpleActionListener class implements the interface by defining that function.

Now that we have a class that implements ActionListener, we can create an instance of this class and add it to a JButton:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JButton;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JButton button = new JButton("Click me!");

frame.add(button);

SimpleActionListener listener = new SimpleActionListener();

button.addActionListener(listener);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

This code creates a JFrame and adds a JButton to it. Then it creates an instance of our SimpleActionListener class and passes it into the addActionListener() function of our JButton instance. Then the code sets the size of the window and displays it.

Now, when we click the button, the actionPerformed() function inside our SimpleActionListener class is called, and "Clicked!" is printed to the console.

We probably want to do something a little more involved than just printing something to the console when the user clicks the button, though. Let’s say we want to change the text on the button to show how many times the user has clicked. To do that, we need a reference to the JButton instance inside our SimpleActionListener class.

One way to get that reference is through the ActionEvent instance passed in as a parameter to the actionEvent() function. That class contains a getSource() function, which returns the object that generated the event: in our case, this is our JButton instance! But the reference is an Object reference, so you have to cast it to JButton to use functions from the JButton class.

That might sound confusing, but it looks like this:

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import javax.swing.JButton;

public class SimpleActionListener implements ActionListener{

private int clicks = 0;

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event){

clicks++;

JButton clickedButton = (JButton) event.getSource();

clickedButton.setText("Clicks: " + clicks);

}

}

Now our class contains a clicks variable that keeps track of how many times the user has clicked. In the actionPerformed() function, that variable is incremented. Then the code calls the event.getSource() function, casts the returned reference to JButton and stores it in the clickedButton variable. Finally, the code calls the setText() function of that JButton to display the click count. And since the clickedButton variable points to the same JButton instance that we’ve added to our JFrame, our displayed button’s text is updated.

But what if we wanted to update a different component that wasn’t the source of the event? For example, what if we want to update a JLabel whenever we click a JButton? To do that, we have to pass a reference to the JLabel ourselves. We could use a setter function, or we could use a constructor that took the JLabel as an argument:

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import javax.swing.JLabel;

public class SimpleActionListener implements ActionListener{

private int clicks = 0;

private JLabel label;

public SimpleActionListener(JLabel label){

this.label = label;

}

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event){

clicks++;

label.setText("Clicks: " + clicks);

}

}

Now our SimpleActionListener class takes a JLabel argument in its constructor, and it updates the text of that JLabel whenever the actionPerformed() function is called.

Back in our main() function, we have to create a JLabel instance, add it to the window, and pass it into the constructor of our SimpleActionListener class. Putting it all together, it looks like this:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.JButton;

import javax.swing.JLabel;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JPanel panel = new JPanel();

JButton button = new JButton("Click me!");

panel.add(button);

JLabel label = new JLabel("Clicks: 0");

panel.add(label);

SimpleActionListener listener = new SimpleActionListener(label);

button.addActionListener(listener);

frame.add(panel);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

This code creates a JFrame and a JPanel, and then it creates a JButton and a JLabel and adds both of them to the JPanel. The code then passes the JLabel into the SimpleActionListener constructor, and it adds that listener to the JButton. Then it adds the JPanel to the JFrame and shows the window.

Now when the user clicks the button, the text on the JLabel is updated.

The above examples use a named, top-level class that implements the ActionListener interface, but rememeber that you can also implement an interface using inner classes and anonymous classes. This lets us include our listener code with our GUI code, like this:

ActionListener listener = new ActionListener(){

int clicks = 0;

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event){

clicks++;

label.setText("Clicks: " + clicks);

}

};

button.addActionListener(listener);

Now instead of using a separate SimpleActionListener class, we’re using an anonymous class that implements the ActionListener interface. The logic is the same, but note that we’re no longer passing the JLabel into a constructor. Because this is an anonymous inner class, it has access to the variables in its enclosing scope (in this case, the main() function). That means it can reference the label variable directly.

You can also shorten that into a single statement:

button.addActionListener(new ActionListener(){

int clicks = 0;

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event){

clicks++;

label.setText("Clicks: " + clicks);

}

});

Now instead of storing the instance of our anonymous class in a variable, we pass it directly into the addActionListener() function.

Anonymous classes are often used when specifying listeners, which lets us keep logic related to a single component together, and avoids creating a bunch of classes we only use once.

There are a bunch of different kinds of event listeners, and you can add multiple listeners to the same component. You can also add listeners to the overall JFrame window. Here’s an example that adds a MouseListener and a KeyListener to the JFrame:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.JButton;

import javax.swing.JLabel;

import java.awt.event.MouseListener;

import java.awt.event.MouseEvent;

import java.awt.event.KeyListener;

import java.awt.event.KeyEvent;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

JLabel label = new JLabel();

frame.addMouseListener(new MouseListener(){

public void mouseClicked(MouseEvent me){

label.setText("Mouse clicked. (" + me.getX() + ", " + me.getY() + ")");

}

public void mouseEntered(MouseEvent me){

label.setText("Mouse entered. (" + me.getX() + ", " + me.getY() + ")");

}

public void mouseExited(MouseEvent me){

label.setText("Mouse exited. (" + me.getX() + ", " + me.getY() + ")");

}

public void mousePressed(MouseEvent me){

label.setText("Mouse pressed. (" + me.getX() + ", " + me.getY() + ")");

}

public void mouseReleased(MouseEvent me){

label.setText("Mouse released. (" + me.getX() + ", " + me.getY() + ")");

}

});

frame.addKeyListener(new KeyListener(){

public void keyPressed(KeyEvent ke){

label.setText("Key pressed. (" + ke.getKeyChar() + ")");

}

public void keyReleased(KeyEvent ke){

label.setText("Key released. (" + ke.getKeyChar() + ")");

}

public void keyTyped(KeyEvent ke){

label.setText("Key typed. (" + ke.getKeyChar() + ")");

}

});

frame.add(label);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

This might seem like a lot, but this code is only really doing a few things. First it creates a JFrame and a JLabel, and then it adds a MouseListener to that JFrame. The MouseListener interface requires five functions: mouseClicked(), mouseEntered(), mouseExited(), mousePressed(), and mouseReleased(). In each of those functions, the text of the JLabel is set based on the values of the getX() and getY() functions, which return the position of the cursor.

Next, a KeyListener is added to the JFrame. The KeyListener interface requires three functions: keyPressed(), keyReleased(), and keyTyped(). In each of those functions, the text of the JLabel is set based on the value of the getKeyChar() function, which returns the key the user is hitting.

Then the JLabel is added to the JFrame, and the JFrame is displayed.

The result is a window that displays information about the the events generated by the mouse and keyboard:

There are a bunch of other event listeners, and you should check out the Java API and this tutorial to learn more about them.

Custom Painting

So far, we’ve learned how to create a GUI using the components that come with Swing. We can customize these components by specifying their layout, font size, color, border, etc. But if we want to do our own drawing, we have to create our own component that performs custom painting.

Looking at the Java API, we can see that Swing components inherit a function named paintComponent() from the JComponent class. Basically, the paintComponent() function draws the stuff inside the component.

So, to create a custom component, we can extend a component class and override the paintComponent() function. Then we can put our drawing code inside the paintComponent() function. The JPanel class gives us a reasonable starting point since it’s just a blank component, so let’s extend that.

That sounds confusing, but it looks like this:

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import java.awt.Graphics;

public class CustomComponent extends JPanel{

@Override

public void paintComponent(Graphics g){

super.paintComponent(g);

g.drawOval(10, 10, 200, 200);

}

}

This code defines a class that extends the JPanel class and overrides the paintComponent() function, which takes a Graphics instance as an argument. The code then calls the super class’s paintComponent() function, which handles stuff like drawing the background of the component. Then the code calls the drawOval() function, which draws an oval on the component.

And because the class extends the JPanel class, we can use it just like any other component! We can add it to another JPanel or a JFrame to display it:

import javax.swing.JFrame;

public class MyGui{

public static void main(String[] args){

JFrame frame = new JFrame("Happy Coding");

frame.setDefaultCloseOperation(JFrame.EXIT_ON_CLOSE);

CustomComponent customComponent = new CustomComponent();

frame.add(customComponent);

frame.setSize(300, 300);

frame.setVisible(true);

}

}

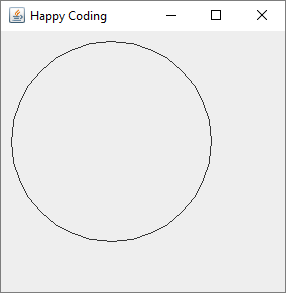

This code creates an instance of the CustomComponent class and adds it to a JFrame. This displays our component in a window, and we can see the circle we’re drawing:

In Swing, drawing is done through the Grahpics instance passed into the paintComponent() function. You should check out the Java API to read about all the different functions you can call, and they should look pretty similar to Processing’s drawing functions. That’s because Processing is built on top of Java! In fact, Processing’s drawing functions actually end up calling Swing’s Graphics functions.

However, there are a few differences between Processing’s drawing and Swing’s drawing:

-

The

paintComponent()function is NOT automatically called 60 times per second. In fact, you don’t really have total control over when it’s called! It can be called when the window is resized, when you move the window, when other windows are moved, or whenever Swing feels like it. You should not rely onpaintComponent()for timing! -

Similarly, you should not put any “business logic” inside your

paintComponent()function. That means stuff like user input should be handled using event listeners, and animation should be handled outside of thepaintComponent()function. We’ll get to that in a second. -

The

Graphicsclass contains very similar functions to Processing. Processing’sellipse()function is thedrawOval()function in Swing,rect()isdrawRect(), etc. There are a few differences though. For example, Processing uses a stroke color to draw both the shape’s outline and a fill color to draw its inner area. Swing splits that up into two functions, so to draw a circle with an outline you would first callfillEllipse()and thendrawEllipse()to draw an outline around it. Similarly, both Processing and Swing use a coordinate system where0,0is in the upper-left corner, but some of Swing’s individual functions are a little different: thedrawOval()function takes the upper-left corner of the circle, not the center. -

Remember that custom painting happens in a class that extends

JPanel, so we have access to the functions defined by that class (and all of its super classes). For example, thegetWidth()andgetHeight()functions return the width and height of the component.

Here’s an example that shows some of what I’m talking about:

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import java.awt.Graphics;

import java.awt.Color;

public class CustomComponent extends JPanel{

public CustomComponent(){

setBackground(new Color(0, 255, 255));

}

@Override

public void paintComponent(Graphics g){

super.paintComponent(g);

g.setColor(Color.YELLOW);

g.fillOval(10, 10, getWidth()-20, getHeight()-20);

g.setColor(Color.BLACK);

g.drawOval(10, 10, getWidth()-20, getHeight()-20);

}

}

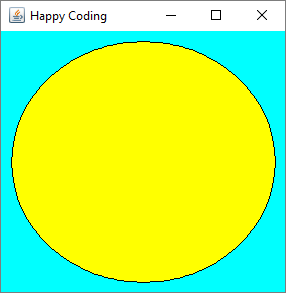

Again, this code creates a subcalss of JPanel. It also defines a constructor and calls the setBackground() function (which it inherits from a superclass) and passes in a Color instance to set the background color. That line of code uses the Color constructor, which takes RGB arguments to create a color.

Then in the paintComponent() function, it first calls the super class’s paintComponent() function, which handles stuff like drawing the background color. Then the code calls the setColor() function, which changes the drawing color. This line of code uses the static variable YELLOW defined in the Color class, which is an easy way to use predefined colors instead of going through RGB every time. Then the code calls the fillOval() function to draw the inside of a circle. Then it sets the color to black and draws the outline.

Our main class code doesn’t change. It can still just treat our CustomComponent class as a component and add it to a JFrame to display it.

Timers

Like I mentioned above, you have no control over when the paintComponent() function is called, so you shouldn’t use paintComponent() for stuff like animation or timing.

Instead, you should use the Timer class in the javax.swing package. The Timer class lets you specify an interval and an ActionListener, and the Timer will call the actionPerformed() function of that ActionListener at that interval. Here’s a simple example:

ActionListener listener = new ActionListener(){

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e){

System.out.println("Timer fired!");

}

}

Timer timer = new Timer(1000, listener);

timer.start();

This code creates an implementation of ActionListener using an anonymous class, and in its actionPerformed() function it just prints a message to the console. Then the code calls the Timer constructor, passing in an interval of 1000 milliseconds as well as the ActionListener it just created. Then it calls the start() function on that Timer instance. This causes the Timer to call the actionPerformed() function every 1000 milliseconds, which results in the message being printed to the console one time per second.

Note that we could also have done it in a single statement:

new Timer(1000, new ActionListener(){

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e){

System.out.println("Timer fired!");

}

}).start();

Either format is fine, or you could create a separate top-level class that implements ActionListener instead of using an anonymous class. You’ll see a mix of all of these approaches in the real world.

Anyway, now that we know how to create a Timer to call code at an interval, and we know how to do custom painting, we can combine those ideas to create an animation!

The idea is the same as it was in Processing: we want to base our drawing off of variables, and we want to change those variables over time so that the drawing changes over time. Only instead of doing the drawing and changing in the same function, we want to split that up into two functions: one that contains the “business logic” of updating the variables and is triggered by the Timer, and the paintComponent() function that draws a frame based on those variables.

Putting it all together, it looks like this:

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.Timer;

import java.awt.Graphics;

import java.awt.Color;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

public class CustomComponent extends JPanel{

private int circleY = 0;

public CustomComponent(){

setBackground(new Color(0, 255, 255));

new Timer(16, new ActionListener(){

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e){

step();

repaint();

}

}).start();

}

private void step(){

circleY++;

if(circleY > getHeight()){

circleY = 0;

}

}

@Override

public void paintComponent(Graphics g){

super.paintComponent(g);

g.setColor(Color.RED);

g.fillOval(getWidth()/2 - 10, circleY, 20, 20);

}

}

This code defines a CustomComponent class that extends JPanel and contains a circleY variable that starts out at 0. In the constructor, the background color is set, and a Timer is created. Every 16 milliseconds (60 times per second), the Timer calls the step() function, which increments the circleY variable and resets its value if it becomes greater than the height of the component. Then the Timer calls the repaint() function, which is another inherited function that tells the component to redraw itself. This (eventually) causes the overridden paintComponent() function to be called, which draws the circle to the screen.

Some stuff to notice:

-

We’re using an anonymous inner class to create our implementation of

ActionListenerthat we’re passing into ourTimer, which means that we can access functions from the outerCustomComparatorclass inside theactionPerformed()function. This is why we can callstep()andrepaint()directly. -

We’re keeping our “business logic” isolated from our painting code. It’s a good idea to keep things separated like this.

-

You should think of the

repaint()function as a suggestion for the component to redraw itself. This does not always mean thepaintComponent()function will be called right away, and this isn’t the only time thepaintComponent()function will be called! For example, on a busy system, you can callrepaint()multiple times before the component has a chance to redraw itself. If you callrepaint()10 times before the component can redraw itself, you still only get one call topaintComponent()! That’s why it’s important to keep your logic separate, so you can more reliably call it.

Again, our main code doesn’t change, and we can just create an instance of this class and add it to a JFrame to show it:

We can also add an event listener to add user interaction to our animation:

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.Timer;

import java.awt.Graphics;

import java.awt.Color;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import java.awt.event.MouseListener;

import java.awt.event.MouseEvent;

public class CustomComponent extends JPanel{

int circleX = 150;

int circleY = 0;

public CustomComponent(){

setBackground(new Color(0, 255, 255));

addMouseListener(new MouseListener(){

public void mousePressed(MouseEvent me){

circleX = me.getX();

circleY = me.getY();

}

public void mouseClicked(MouseEvent me){}

public void mouseEntered(MouseEvent me){}

public void mouseExited(MouseEvent me){}

public void mouseReleased(MouseEvent me){}

});

new Timer(16, new ActionListener(){

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e){

step();

repaint();

}

}).start();

}

private void step(){

circleY++;

if(circleY > getHeight()){

circleY = 0;

}

}

@Override

public void paintComponent(Graphics g){

super.paintComponent(g);

g.setColor(Color.RED);

g.fillOval(circleX - 10, circleY, 20, 20);

}

}

This is the same code as before, but now it adds a MouseListener that moves the circle to wherever the cursor is when the user presses the mouse button.

And just to show you another approach: instead of using anonymous classes for our listeners, we could have implemented the interfaces in our class, like this:

import javax.swing.JPanel;

import javax.swing.Timer;

import java.awt.Graphics;

import java.awt.Color;

import java.awt.event.ActionListener;

import java.awt.event.ActionEvent;

import java.awt.event.MouseListener;

import java.awt.event.MouseEvent;

public class CustomComponent extends JPanel implements ActionListener, MouseListener{

int circleX = 150;

int circleY = 0;

public CustomComponent(){

setBackground(new Color(0, 255, 255));

addMouseListener(this);

new Timer(16, this).start();

}

private void step(){

circleY++;

if(circleY > getHeight()){

circleY = 0;

}

}

@Override

public void paintComponent(Graphics g){

super.paintComponent(g);

g.setColor(Color.RED);

g.fillOval(circleX - 10, circleY, 20, 20);

}

@Override

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent e){

step();

repaint();

}

@Override

public void mousePressed(MouseEvent me){

circleX = me.getX();

circleY = me.getY();

}

public void mouseClicked(MouseEvent me){}

public void mouseEntered(MouseEvent me){}

public void mouseExited(MouseEvent me){}

public void mouseReleased(MouseEvent me){}

}

This code does the exact same thing as before. But now instead of using anonymous inner classes to implement the ActionListener and MouseListener interfaces, our class implements them by defining the body of their respective functions. Then we use the this keyword to pass a self-reference into the Timer constructor and addMouseListener() function. Since this class implements those interfaces, it can be treated as its own ActionListener or MouseListener.

Either approach is fine, and neither is more or less correct than the other. You could also split each listener into its own separate top-level class in its own file. Which approach you use depends on what makes more sense to you and how this stuff fits into your brain.

Other Resources

This tutorial isn’t meant to show you every detail about every single thing you can do in Swing. It’s meant to introduce you to the basic concepts Swing is built on, so you can then consult other resources to accomplish your goals. Here are a few places to get you started:

- As always, the Java API is your best friend.

- The official Swing tutorial is a good place to start and links to a bunch of other resources.

- Using Swing Components introduces a ton of components and how to use them.

- Laying out Components introduces different layout managers. The visual guide gives you a quick preview of what each one looks like.

- Writing Event Listeners talks more about different types of event listeners.

- Performing Custom Painting goes into more detail about doing your own drawing.

If you’re still confused after reading through the documentation, you can always Google stuff like “Java Swing set JButton border” for example. The Swing tag on Stack Overflow is also very active, but make sure you do a search before asking a question.

And of course, you can always ask questions on the Happy Coding forum!

Homework

- Create a GUI that does something useful, or something that’s not useful! Get creative!

- Take some of your old Processing sketches and rewrite them using Swing.