Creating Classes

Creating Classes

- Static

- The

main()Function - Mixing Static and Non-Static

- Multiple Classes

- The

non-static variable cannot be referenced from a static contextError - Passing Data Between Classes

- Packages

- Access Modifiers

- Summary

- Homework

Remember from the Processing tutorials that you can create a class to store variables and functions in a single unit, and then you can create instances of that class using the new keyword.

Let’s say we have this class:

public class Message{

String myMessage;

public Message(String myMessage){

this.myMessage = myMessage;

}

public void printMessage(){

System.out.println(myMessage);

}

}

This code creates a Message class that contains a String variable named myMessage. It has a constructor that sets that variable, and a printMessage() function that prints it to the console.

Now we can create instances of that class using the new keyword, and we can call functions on those instances:

Message messageOne = new Message("Hello");

Message messageTwo = new Message("Bonjour");

Message messageThree = new Message("Hola");

messageOne.printMessage(); //prints Hello

messageTwo.printMessage(); //prints Bonjour

messageThree.printMessage(); //prints Hola

These variables are all of the same class, so they have the same fields and function names. But they’re different instances, so the values of those fields are different.

Static

The static keyword signifies that a variable or function belongs to the overall class, not to a particular instance. It’s like the variable or function is shared between all instances of a class. Let’s look at an example.

To make a variable or function static, just add the static keyword to its declaration. This class contains a static variable and a static function:

public class StaticExample{

static int myNumber;

public StaticExample(int myNumber){

this.myNumber = myNumber;

}

public static void printNumber(){

System.out.println(myNumber);

}

}

This class contains a static variable named myNumber, and a constructor that sets that variable. It also contains a static function named printNumber() that prints the variable.

Now let’s write some code that uses this class:

StaticExample one = new StaticExample(42);

StaticExample two = new StaticExample(100);

one.printNumber();

two.printNumber();

You might expect this code to print 42 and then 100, but it actually prints out 100 twice!

This is because the myNumber variable is static, so both the one and two instances share the same value. When we pass 100 into the constructor and set the myNumber variable, we’re setting it for the whole class, not a particular instance. Furthermore, the printNumber() function is also static, so even though it looks like we’re calling functions on two different instances, we’re actually just calling the same class-level function twice.

This is confusing, which is why you should never access a static variable or function using an instance. Instead, always use the class name!

With that rule in mind, our StaticExample.java file should look like this:

public class StaticExample{

static int myNumber;

public StaticExample(int myNumber){

StaticExample.myNumber = myNumber;

}

public static void printNumber(){

System.out.println(StaticExample.myNumber);

}

}

Notice that we’re using StaticExample.myNumber to make it obvious that it’s a static variable. Now we can see that the constructor is really setting a class-level variable, not an instance variable. The rest of our code would look like this:

StaticExample one = new StaticExample(42);

StaticExample two = new StaticExample(100);

StaticExample.printNumber();

StaticExample.printNumber();

Now it’s more obvious that we’re really just calling the same function twice in a row.

The main() Function

Now you understand what the static part of the main() function means. It means that the main() function doesn’t belong to any paticular instance. It belongs to the class itself.

You can put code inside the main() function that creates instances of the class. Putting it all together, here’s the above example in a single class file:

public class Message{

String myMessage;

public Message(String myMessage){

this.myMessage = myMessage;

}

public void printMessage(){

System.out.println(myMessage);

}

public static void main(String[] args){

Message messageOne = new Message("Hello");

Message messageTwo = new Message("Bonjour");

Message messageThree = new Message("Hola");

messageOne.printMessage(); //prints Hello

messageTwo.printMessage(); //prints Bonjour

messageThree.printMessage(); //prints Hola

}

}

Try compiling and running this class! If it seems confusing, try thinking about the main() function separately from the rest of the class.

- The class contains one instance variable (just another name for a non-static variable) named

myMessage, which is set by the constructor. Then the class contains a non-staticprintMessage()function that prints themyMessagevariable. - The

main()function creates three instances of theMessageclass, and then calls theprintMessage()function on each instance.

Mixing Static and Non-Static

All of this might not seem very useful other than explaining what the static part of the main() method means. But static variables and functions can be useful when you want to share data between instances, or when you don’t want to tie a variable or function to a particular instance.

Note that you’ve already been using a static variable! The System class has a static variable named out, which is an instance of the PrintStream class, which contains a println() function. Look it up in the Java API!

Let’s add a static variable and function to our Message class:

public class Message{

static int instanceCount = 0;

String myMessage;

public Message(String myMessage){

this.myMessage = myMessage;

Message.instanceCount++;

}

public void printMessage(){

System.out.println(myMessage);

}

public static void printInstanceCount(){

System.out.println("There are " + Message.instanceCount + " instances of Message.");

}

public static void main(String[] args){

Message messageOne = new Message("Hello");

Message messageTwo = new Message("Bonjour");

Message messageThree = new Message("Hola");

messageOne.printMessage(); //prints Hello

messageTwo.printMessage(); //prints Bonjour

messageThree.printMessage(); //prints Hola

Message.printInstanceCount(); //prints 3

}

}

Try compiling and running this class! If it seems confusing, try thinking about the main() function separately from the rest of the class.

- The class contains two variables: an instance (non-static) variable named

myMessageand astaticvariable namedinstanceCount. The constructor sets themyMessagevariable and increments theinstanceCountvariable. Then the class contains a non-staticprintMessage()function that prints themyMessagevariable, and astaticprintInstanceCount()function that prints theinstanceCountvariable. - The

main()function creates three instances of theMessageclass, calls theprintMessage()function on each instance, and then calls theprintInstanceCount()statically by using the class name.

In this example, the instanceCount variable holds the total number of instances of the Message class, which isn’t particular to any one instance of the class, so we make it static. Similarly, the printInstanceCount() function isn’t different between instances, so we make it static as well.

Multiple Classes

It might seem confusing to have a main() function inside a class that creates instances of that class. Just remember that the main() function is static, so it’s “outside” any particular instance. It might be easier to understand if you put the main() function inside a different class.

Let’s start with the first class:

public class Message{

static int instanceCount = 0;

String myMessage;

public Message(String myMessage){

this.myMessage = myMessage;

instanceCount++;

}

public void printMessage(){

System.out.println(myMessage);

}

public static void printInstanceCount(){

System.out.println("There are " + instanceCount + " instances of Message.");

}

}

Save this to a file named Message.java. This is the same class we’ve been looking at. Notice that it doesn’t have a main() method, so you can’t run it.

Now let’s create another class that contains a main() method that uses our first class:

public class MessageMain{

public static void main(String[] args){

Message messageOne = new Message("Hello");

Message messageTwo = new Message("Bonjour");

Message messageThree = new Message("Hola");

messageOne.printMessage(); //prints Hello

messageTwo.printMessage(); //prints Bonjour

messageThree.printMessage(); //prints Hola

Message.printInstanceCount(); //prints 3

}

}

Save this to a file named MessageMain.java. This class just contains a main() method with the same code we’ve been running. Hopefully this makes the code a little easier to think about.

Now you’ve got two files: Message.java and MessageMain.java. You need to compile both of these classes. You have a couple ways to do that:

- You could just compile

MessageMain.javaby typingjavac MessageMain.javaand pressing enter. The compiler will see that theMessageMainclass uses theMessageclass, so it will automatically compile both files. - Or you could compile all of your classes by typing

javac *.javaand pressing enter. This tells the compiler to compile every file that ends with a.javaextension.

Either way, you should end up with two more files: Message.class and MessageMain.class. Since our main() function is inside the MessageMain class, that’s the one we want to run by typing java MessageMain and pressing enter.

Most Java applications will use a bunch of different class files, and it’s pretty normal to have an “entry point” class that contains just a main() function that uses other classes.

The non-static variable cannot be referenced from a static context Error

Let’s looks at this example program:

public class Cat{

String name = "Stanley";

public static void main(String[] args){

Cat catOne = new Cat();

catOne.name = "Fluffy";

Cat catTwo = new Cat();

catTwo.name = "Professor Meow";

System.out.println("First cat's name: " + catOne.name);

System.out.println("Second cat's name: " + catTwo.name);

}

}

This Cat class contains one instance (non-static) variable called name, with a default value of "Stanley". Then the main() function creates two instances of the Cat class, giving each of them their own value for the name variable. Finally, this code will print out two different names, because each instances of Cat has its own name value.

All of that is good so far. But I promise that you will eventually write code that looks like this:

public class Cat{

String name = "Stanley";

public static void main(String[] args){

System.out.println(name);

}

}

If you try to compile this class, you’ll get a compiler error:

Cat.java:6: error: non-static variable name cannot be referenced from a static context

System.out.println(name);

^

1 error

This error is telling you that you’re trying to use a non-static variable (in this case, the name variable) from a static function (in this case, the main() function). You can’t access non-static variables from static functions, so the compiler gives you this error.

This might sound confusing, but think about it this way: when you type the name variable, you’re asking for a particular cat’s name. But you haven’t specified which instance to use, so the compiler is saying “I can’t give you a cat’s name if you don’t tell me which cat’s name you want!”

To fix this error, you might be tempted to make the name variable static, like this:

public class Cat{

static String name = "Stanley";

public static void main(String[] args){

System.out.println(name);

}

}

Don’t do this! Making the name variable static will fix this particular error, but it completely breaks the point of instance variables. What would happen if we tried to create multiple instances of this class?

public class Cat{

static String name = "Stanley";

public static void main(String[] args){

Cat catOne = new Cat();

catOne.name = "Fluffy";

Cat catTwo = new Cat();

catTwo.name = "Professor Meow";

System.out.println("First cat's name: " + catOne.name);

System.out.println("Second cat's name: " + catTwo.name);

}

}

Now both cats will have the same name, because the name variable is not particular to any one instance.

Instead of making the name variable static, what we probably should have done is created an instance of Cat and got the name function that way:

public class Cat{

String name = "Stanley";

public static void main(String[] args){

Cat cat = new Cat();

System.out.println(cat.name);

}

}

Or we should have moved our logic into a function in the Cat class and used that instead of putting logic in the main() method:

public class Cat{

String name = "Stanley";

public void printName(){

System.out.println(name);

}

public static void main(String[] args){

Cat cat = new Cat();

cat.printName();

}

}

This code works, because the main() method is creating an instance of the Cat class, and then calling the printName() function of that instance. The printName() function is non-static, so it can access the non-static name variable.

Passing Data Between Classes

Let’s look at another example. Let’s say we have two classes. First, we have a Main class:

public class Main{

String message;

public Main(String message){

this.message = message;

}

public void runProgram(){

MessagePrinter mp = new MessagePrinter();

mp.printMessage();

}

public static void main(String[] args){

Main main = new Main("Happy Coding");

main.runProgram();

}

}

This class contains one variable named message, which is set by the constructor. It also has a runProgram() function that creates an instance of MessagePrinter (which we’ll see in a second) and calls its printMessage() function. The main() function just creates an instance of Main, passing in a String value, and then calls the runProgram() function on that instance.

Now we try to create a MessagePrinter class whose job it is to print the message variable from the Main class. How would we do that?

public class MessagePrinter{

public void printMessage(){

//I want to print the message variable from the Main class!

}

}

Again, you might be tempted to make the message variable static, so you could do this:

public class MessagePrinter{

public void printMessage(){

System.out.println(Main.message);

}

}

Don’t do this! Again, this completely defeats the purpose of instance variables. What if you eventually want to have more than one instance of the Main class?

Instead, you need to pass the data from the Main class to the MessagePrinter class. For example, you could add a parameter to the printMessage() function:

public class MessagePrinter{

public void printMessage(String message){

System.out.println(message);

}

}

Then the Main class could pass its message variable in as an argument:

public void runProgram(){

MessagePrinter mp = new MessagePrinter();

mp.printMessage(message);

}

Another option is to pass the instance of Main into the MessagePrinter class. You could pass it as an argument to the constructor:

public class MessagePrinter{

Main main;

public MessagePrinter(Main main){

this.main = main;

}

public void printMessage(){

System.out.println(main.message);

}

}

Now the MessagePrinter class has an instance of Main, so it can get to the message variable that way. (Better yet, you could use a getter function instead. See the Access Modifiers section below.)

Now when the Main class creates an instance of MessagePrinter, it needs to pass a reference to itself into the constructor. We can use the this keyword for that!

public void runProgram(){

MessagePrinter mp = new MessagePrinter(this);

mp.printMessage();

}

You should never use the static keyword because you think it gets rid of errors or because you think it’s easier to pass data between classes. Use the above approaches instead!

Packages

As your programs get more complicated and you start using more class files, you might want to split them up into packages. Packages are collections of related classes, and they let you organize your files into folders.

Using a package is really two things:

- Oranize your

.javafiles into folders. - Add package declarations to those classes.

Let’s look at a concrete example. Let’s say we want to create a set of .java files inside a folder structure, like this:

- MyZoo

- main

- Main.java

- animals

- Zoo.java

- mammals

- Cat.java

- reptiles

- Dinosaur.java

- main

In other words, we have a single directory named MyZoo that holds our whole program. The MyZoo folder contains two other folders: main and animals. The main folder contains a single file named Main.java. The animals folder contains a file named Zoo.java, and two sub-folders named mammals and reptiles. The mammals folder contains a Cat.java file, and the reptiles folder contains a Dinosaur.java file.

Let’s start with the Cat.java file:

package animals.mammals;

public class Cat{

public void meow(){

System.out.println("Meow!");

}

}

The only interesting thing here is the first line at the top. This is a package declaration, and it should always be the first line in a file. This line tells Java that the Cat class is inside the animals.mammals package, which matches the .java file being inside the animals/mammals subdirectory.

Similarly, Dinosaur.java has a package declaration putting it in the animals.reptiles package:

package animals.reptiles;

public class Dinosaur{

public void roar(){

System.out.println("Roar!");

}

}

The Zoo.java file is a little more interesting:

package animals;

import animals.mammals.Cat;

import animals.reptiles.Dinosaur;

public class Zoo{

Cat cat = new Cat();

Dinosaur dinosaur = new Dinosaur();

public void visit(){

System.out.println("Let's visit the cat.");

cat.meow();

System.out.println("Let's visit the dinosaur.");

dinosaur.roar();

}

}

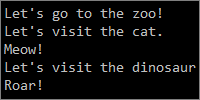

This code starts with a package declaration saying it’s in the animals package. Then it imports our first two classes using their package and class names. That lets us use those classes inside the Zoo class.

Finally, our Main.java file does something similar:

package main;

import animals.Zoo;

public class Main{

public static void main(String[] args){

Zoo zoo = new Zoo();

System.out.println("Let's go to the zoo!");

zoo.visit();

System.out.println("That was a fun day at the zoo.");

}

}

This code starts with a package declaration, then imports the animals.Zoo class. Then it contains a main() method that uses the Zoo class. Hooray! ![]()

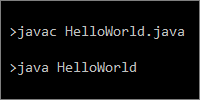

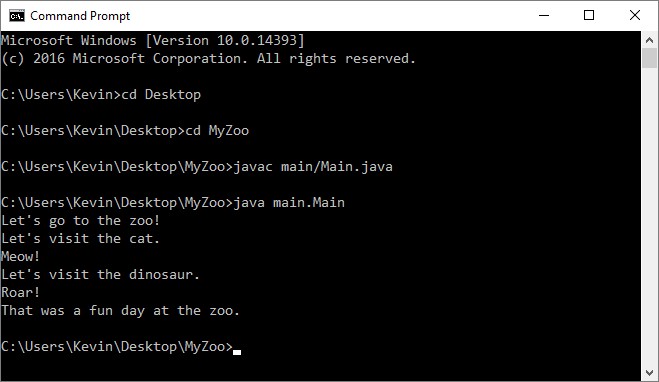

To compile this program, we’d open a command prompt to the top-level MyZoo directory. From there, we’d type javac main/Main.java to compile the Main.java class. Since this class uses the Zoo class, which uses Cat and Dinosaur classes, compiling Main.java causes every class to be compiled. But note that you have to do this from the top-level MyZoo directory!

Now that we’ve compiled our classes, we can run our program by typing java main.Main and pressing enter. Note that we also have to do this from the top-level MyZoo directory, and notice that we use dots instead of slashes!

The whole process looks like this:

Access Modifiers

You might have noticed the public keyword in some of our code. That’s called an access modifier, which tells Java who can access a member (a variable or function).

There are a few access modifiers:

-

publicmembers can be accessed by any class. -

privatemembers can only be accessed by that class. -

protectedmembers can be accessed by classes in the same package or by subclasses (it’s okay if you don’t know what this means yet). - If you don’t specify an access modifier, the member can be accessed by classes in the same package.

This might not seem useful for simple code or code that only you work on. But it becomes really important if you’re writing code with other people!

Usually, most variables are private, and only the constructors and functions that other people should use are public.

For example, let’s say you and another person are working together, with a goal of creating a program that only prints out three things. You split the work up: you’ll create a class that contains the logic for counting the things that have been printed, and the other person will pass data into your class.

So, you write your code:

public class PrintThreeTimes{

int timesPrinted = 0;

public void print(String thing){

if(timesPrinted < 3){

System.out.println(thing);

timesPrinted++;

}

else{

System.out.println("Sorry, I can't print anything else.");

}

}

}

This code works, and the print() function will only print the parameter three times. After that it will print an error message.

Now, your partner comes along and writes this code, which uses your class:

public class SomebodyElsesCode{

public static void main(String[] args){

PrintThreeTimes ptt = new PrintThreeTimes();

ptt.print("thing one");

ptt.print("thing two");

ptt.print("thing three");

ptt.print("thing four");

}

}

This correctly prints out three things and then an error message:

thing one

thing two

thing three

Sorry, I can't print anything else.

However, your partner wasn’t really paying attention, and they think that the goal was to print four things instead of three! They know they aren’t supposed to change the code you wrote, but they also see that the timesPrinted variable is not private. This tells them that they are supposed to change that variable. So they modify their code:

public class SomebodyElsesCode{

public static void main(String[] args){

PrintThreeTimes ptt = new PrintThreeTimes();

ptt.print("thing one");

ptt.print("thing two");

ptt.print("thing three");

ptt.timesPrinted = 0;

ptt.print("thing four");

}

}

Now this code “works” and allows four things to be printed, and your partner submits it. If this is a school assignment, now you’re getting a bad grade. If this is a work assignment, now you’re getting fired! And it could have been avoided if you had simply made the timesPrinted variable private in the first place:

public class PrintThreeTimes{

private int timesPrinted = 0;

public void print(String thing){

if(timesPrinted < 3){

System.out.println(thing);

timesPrinted++;

}

else{

System.out.println("Sorry, I can't print anything else.");

}

}

}

Now nobody else can touch the timesPrinted variable, and they’ll get a compiler error if they try. This tells them that they aren’t supposed to modify the value of the variable. In this example, maybe this causes your partner to read the instructions again, or maybe they ask you about it. Either way, you end up with a better grade and you aren’t fired!

If you want to allow other people to know the value of a variable but not change it, you can use a getter function that just returns the value of the variable:

public class PrintThreeTimes{

private int timesPrinted = 0;

public int getTimesPrinted(){

return timesPrinted;

}

public void print(String thing){

if(timesPrinted < 3){

System.out.println(thing);

timesPrinted++;

}

else{

System.out.println("Sorry, I can't print anything else.");

}

}

}

Now your partner can get the value of the variable, so they can check when the limit has been reached. But they can’t set the value of the variable, so they can’t get you fired.

This is admittedly a dumb example, but it’s not that far-fetched: a “real” program that only has a limited number of connections to a database might use code almost exactly like this.

Real code is going to be much more complicated, so get in the habit of marking your variables private now.

Summary

This was a bit of an information dump, but you’re going to see all of the above sooner rather than later. Processing hid a lot of these details from you, but you need to understand what’s going on behind the scenes when you’re programming in Java.

You don’t have to memorize the stuff in this tutorial. Instead, try to keep the general principles in mind:

- Split your program up into separate classes, and put each class in its own file.

- Use the command line to compile and run your classes.

- Understand

static, but don’t misuse it to pass data between classes. - Understand packages, and split your Java files into directories.

- Make variables

private.

And if you find yourself needing to remember a particular detail (how do I pass data between classes again?), then come back here and read the tutorial again.

Homework

- Expand the zoo example. Add classes for different types of animals, and organize them into packages. Can you think of other packages that might come in handy?