Matrices

Matrices

November 5, 2023

tutorial interviewingBy now, you’ve learned about many data structures and algorithms. From arrays and Strings, to maps, sets, queues, and stacks, to node-based data structures like linked lists, trees, and graphs.

This guide introduces one more data structure: matrices, or two-dimensional arrays. We already talked about arrays, but matrices are so common in interview questions that they deserve their own guide.

Matrix questions broadly fall into two categories: questions involving iterating over or moving the elements of the matrix in a particular order, and questions treating the matrix as a search space.

Matrix Representation

Matrices are generally represented as a two-dimensional array, which I think of as a table:

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

0 |

A | B | C | D |

1 |

E | F | G | H |

2 |

I | J | K | L |

3 |

M | N | O | P |

In this case, the table has four rows and four columns. You can reference each cell by its row number and column number. For example, the coordinate 1,2 references the cell at row 1 and column 2, which in this table is G.

That might feel counter-intuitive, because most people are accustomed to thinking in terms of x,y coordinates. If that’s how you think of coordinates, then you’d expect 1,2 in the above table to be J instead of G.

But think about it in terms of a 2D array:

String[][] matrix = {

{"A", "B", "C", "D"},

{"E", "F", "G", "H"},

{"I", "J", "K", "L"},

{"M", "N", "O", "P"},

};

// Prints "G"

System.out.println(matrix[1][2]);

If you run this code, you’ll see that matrix[1][2] points to G.

This is because in Java, a 2D array is really an array that contains arrays. That means you can do this:

String[][] matrix = {

{"A", "B", "C", "D"},

{"E", "F", "G", "H"},

{"I", "J", "K", "L"},

{"M", "N", "O", "P"},

};

String[] row = matrix[1]; // {"E", "F", "G", "G"}

String cell = row[2]; // "G"

// Prints "G"

System.out.println(cell);

This code creates a 2D array matrix, which is itself an array that contains four arrays. It then asks for the array at index 1 and stores that array in the row variable. Finally, it asks the row array for the element at index 2, which is G.

In other words, the first dimension of the 2D array represents the row, and the second dimension represents the column.

Keeping this in mind is trickier than you might expect!

Iterating and Shifting Elements

A common type of interview question involves iterating over the elements in a matrix in a particular order, or moving the elements in a particular way.

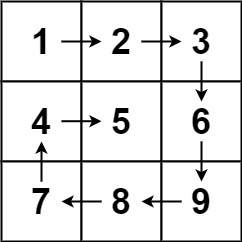

For example, Spiral Matrix asks you to take a matrix and then return the values generated by iterating over the matrix in a spiral path.

{1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 8, 7, 4, 5}

You can do this with a series of for loops, but you have to think very carefully about off-by-one errors and different matrix sizes.

To help you think about a matrix problem, try starting with a small matrix.

- How would you do this with a 1x1 matrix?

- How would you do this with a 2x1 matrix?

- What would need to change for a 1x2 matrix?

- What about both dimensions with a 2x2 matrix?

- As the matrix grows to 3x3, does anything change?

- Finally, what about 3x4 or 4x3 matrices?

Work through a couple examples until you notice a pattern, and then you can work towards solving the problem with arbitrary matrices.

Here’s the code I came up with:

public List<Integer> spiralOrder(int[][] matrix) {

int spiralHeight = matrix.length;

int spiralWidth = matrix[0].length;

int totalCells = spiralWidth * spiralHeight;

// The spiral moves in by 1 layer at a time.

int layer = 0;

List<Integer> path = new ArrayList<>();

// Loop until you visited all the cells.

while(path.size() < totalCells) {

path.addAll(spiralOneLayer(matrix, layer, spiralWidth, spiralHeight));

layer++;

// After each layer, the spiral decreases by 2 units in each dimension.

spiralHeight -= 2;

spiralWidth -= 2;

}

return path;

}

List<Integer> spiralOneLayer(int[][] matrix, int layer, int width, int height) {

List<Integer> path = new ArrayList<>();

// Calculate the boundaries of this spiral layer.

// topRow and leftColumn are just layer, but separating them makes the code more readable.

int topRow = layer;

int bottomRow = layer + height - 1;

int leftColumn = layer;

int rightColumn = layer + width - 1;

// Move from the top-left corner to the top-right corner.

for(int c = leftColumn; c <= rightColumn; c++){

path.add(matrix[layer][c]);

}

// Move from the top-right corner to the bottom-right corner.

for(int r = topRow + 1; r <= bottomRow; r++) {

path.add(matrix[r][rightColumn]);

}

// If this spiral layer is only a single row or column, then the spiral is complete.

if(width == 1 || height == 1) {

return path;

}

// Move from the bottom-right corner to the bottom-left corner.

for(int c = rightColumn - 1; c >= layer; c--) {

path.add(matrix[bottomRow][c]);

}

// Move from the bottom-left corner to the top-left corner.

for(int r = bottomRow - 1; r > layer; r--){

path.add(matrix[r][layer]);

}

return path;

}

This code uses a helper function to calculate one “layer” of the spiral, and then calls that helper function with decreasing sizes to calculate the whole spiral.

This is the code I came up with, but there are other ways to organize this code. How would you do it?

Matrices as Search Spaces

Matrices also lend themselves to another type of question, where a matrix is treated as a search space. These questions are very similar to graph problems, and algorithms like depth-first search, breadth-first search, and Dijkstra’s are still handy for solving them.

In fact, you can think of a matrix as a graph of interconnected nodes!

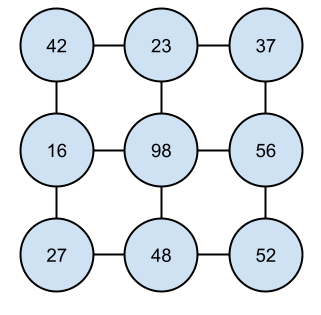

For example, take this matrix:

| 42 | 23 | 37 |

| 16 | 98 | 56 |

| 27 | 48 | 52 |

Conceptually, you can think of it as a graph, where each cell is a node with a value or a cost:

This graph contains nodes, where each node is connected to its neighbors. If you’re currently looking at a certain node, you can traverse to its neighbors. In a graph, you do that by navigating through the connected nodes. With a matrix, you traverse to neighboring cells.

For example, Flood Fill uses a matrix to represent a grid of colors. It asks you to start at a certain cell, and change all of the connected cells with that cell’s color to a different color.

This lends itself pretty naturally to depth-first search or breadth-first search. You can start at the original cell, and then traverse to each of its four neighbors. Whenever you encounter a neighbor with the original color, you change its color and then traverse to all of its neighbors.

Remember that depth-first search can be implemented with recursion or with a stack, and breadth-first search can be implemented with a queue.

Similar to graphs, with matrices you have to be careful that you don’t revisit cells you’ve already visited. Matrices have another gotcha: you shouldn’t traverse to cells that are outside the bounds of the matrix!

Here’s a solution to the Flood Fill problem:

// Helper class that represents a cell in the matrix.

class Cell {

// The Cell's row, i.e. its y coordinate.

int r;

// The cells column, i.e. its x coordinate.

int c;

Cell(int r, int c) {

this.r = r;

this.c = c;

}

// Equivalent Cell instances are added to a HashSet, so we need to override equals.

@Override

public boolean equals(Object other) {

Cell otherCell = (Cell) other;

return this.r == otherCell.r && this.c == otherCell.c;

}

// Equivalent Cell instances are added to a HashSet, so we need to override hashCode.

@Override

public int hashCode() {

return Objects.hash(r, c);

}

}

public int[][] floodFill(int[][] image, int sr, int sc, int color) {

// Track visited Cells to avoid traversing backwards.

Set<Cell> visited = new HashSet<>();

// Only fill Cells that match the original color.

int originalColor = image[sr][sc];

// Track the Cells that still need to be filled.

Deque<Cell> cellsToFill = new ArrayDeque<>();

// Add the starting Cell to the list of Cells to fill.

cellsToFill.addLast(new Cell(sr, sc));

while(!cellsToFill.isEmpty()) {

// Treat the Deque as a Queue to implement BFS.

Cell cell = cellsToFill.removeFirst();

// Don't traverse to already-visted Cells.

if(visited.contains(cell)){

continue;

}

// Don't traverse to Cells outside the matrix.

if(cell.r < 0 || cell.c < 0 || cell.r >= image.length || cell.c >= image[0].length) {

continue;

}

// Stop at Cells that don't contain the original color.

int cellColor = image[cell.r][cell.c];

if(cellColor != originalColor) {

continue;

}

// Set the current Cell's color.

image[cell.r][cell.c] = color;

// Traverse to all of this Cell's neighbors.

cellsToFill.addLast(new Cell(cell.r - 1, cell.c));

cellsToFill.addLast(new Cell(cell.r + 1, cell.c));

cellsToFill.addLast(new Cell(cell.r, cell.c - 1));

cellsToFill.addLast(new Cell(cell.r, cell.c + 1));

visited.add(cell);

}

return image;

}

This code uses a helper Cell class to implement breadth-first search to fill all of the matching connected cells with a new value.

Dynamic Programming

Remember that dynamic programming is a technique where you store the results of calculations so you can reuse them instead of recalculating them over and over again.

This technique is handy for recursive algorithms, but it’s also handy for many matrix problems!

For example, Unique Paths II gives you a matrix that represents an environment that contains obstacles. A robot starts in the upper-left corner, and it can move to the right or down each turn to reach a goal in the lower-right corner.

You might consider using depth-first search or breadth-first search to calculate the number of paths. This animation shows a depth-first search that finds all of the possible paths from the upper-left corner to the lower-right corner:

This approach could work, but notice how many times you need to visit each cell. You end up counting the paths from a single cell multiple times! This algorithm incurs an algorithmic complexity of O(2 ^ n) where n is the number of cells. This works, but it’s not very efficient.

Instead, you can take advantage of the fact that there are two ways to get to a cell: from its left neighbor, or from its top neighbor. So the total number of paths to a cell is the total paths to its left neighbor, plus the total paths to its top neighbor. Think of a few example grids to see what I mean:

| 1 |

In a single-cell grid, there is only one way to get from the upper-left corner to the lower-right corner, because they’re already the same cell.

In a 2x2 grid, there are two paths. You can either move right and then down, or you can move down and then right.

Each cell in this table shows the number of paths leading to it:

| 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 |

Once you know the paths through a 2x2 grid, you can expand that to calculate the paths for a 3x3 grid:

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | 3 | 6 |

To calculate the number of paths to a new cell, you can add the number of paths to its top neighbor to the number of paths to its left neighbor.

This means calculating new paths only requires adding a couple numbers, not searching the whole space over and over again!

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 |

| 1 | 4 | 10 | 20 |

You can use this approach to calculate larger grids, until you reach a grid size that matches the input.

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 15 |

| 1 | 4 | 10 | 20 | 35 |

| 1 | 5 | 15 | 35 | 70 |

This approach calculates the paths through an open matrix. To include obstacles, you can set the number of paths to any cells that contain obstacles to 0, so that subsequent cells will not count those invalid paths.

Putting all of this into code, it looks like this:

public int uniquePathsWithObstacles(int[][] obstacleGrid) {

// The upper-left cell is blocked, so no paths are possible.

if(obstacleGrid[0][0] == 1){

return 0;

}

// Calculate the number of paths to each cell.

int[][] pathsToCell = new int[obstacleGrid.length][obstacleGrid[0].length];

// Assume there is 1 path to the starting cell.

pathsToCell[0][0] = 1;

// Iterate over every cell in the grid.

for(int r = 0; r < obstacleGrid.length; r++) {

for(int c = 0; c < obstacleGrid[r].length; c++) {

// Skip the upper-left cell, since that was already calculated.

if(r == 0 && c == 0) {

continue;

}

// If this cell contains an obstacle, leave its value at 0.

if(obstacleGrid[r][c] == 1){

continue;

}

int pathsFromAbove = 0;

if(r > 0){

pathsFromAbove = pathsToCell[r-1][c];

}

int pathsFromLeft = 0;

if(c > 0) {

pathsFromLeft = pathsToCell[r][c-1];

}

pathsToCell[r][c] = pathsFromAbove + pathsFromLeft;

}

}

// After calculating the whole grid, return the value for the lower-right cell.

return pathsToCell[obstacleGrid.length - 1][obstacleGrid[0].length - 1];

}

Now the code loops over every cell in the matrix, for a runtime complexity of O(n ^ 2). That’s much better than O(2 ^ n)!

Practice Problems

- Flipping an Image

- Valid Sudoku

- Spiral Matrix

- Spiral Matrix II

- Rotate Image

- Set Matrix Zeroes

- Search a 2D Matrix

- Flood Fill

- Island Perimeter

- Word Search

- Unique Paths II

- Number of Islands

- Shortest Path to Get Food

Comments

Happy Coding is a community of folks just like you learning about coding.

Do you have a comment or question? Post it here!

Comments are powered by the Happy Coding forum. This page has a corresponding forum post, and replies to that post show up as comments here. Click the button above to go to the forum to post a comment!